Producing Dairy-Beef: Starting Off on the Right Hoof

This is part two in a series that will explore the opportunities and challenges of dairy-beef cross calves with perspectives from across the value chain including the primary producer, backgrounder, feedlot and processor.

Part one of this series discussed the challenges and opportunities for the feeding and processing sectors. For these sectors to turn a profit from dairy-beef calves, these animals need to have the right start.

For this article, “dairy-beef” refers to an animal with a dairy dam and a beef sire.

Management of dairy-beef calves is variable from operation to operation; however, a strong focus needs to be placed on the early care of these calves. Practices such as adequate colostrum, early health protocols, proper nutrition and housing are all necessary to develop an animal that is desirable for the beef sector.

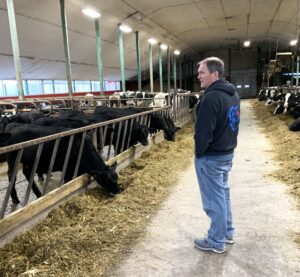

Andrew McCurdy, Bidalosy Farms, Old Barns, NS

Andrew McCurdy’s family began feeding dairy-beef calves in 2015 to increase the value of his non-replacement calves that would not become replacement females in the milking herd. He started using beef sires through artificial insemination to produce dairy-beef calves. “Determining which bulls to use has been a learning curve. Using EPDs to make sire selections is different from the dairy sector which is strictly using genomics,” Andrew says.

In 2018, the McCurdys built a calving barn which would allow them to better handle newborn calves (both conventional dairy and dairy-beef) and give them the best start possible. At first, the barn was equipped with an automatic calf feeder to reduce labour costs.

Since milk replacer alone was costing the operation approximately $4,000 a month, a decision was made to remove the automatic feeder and switch to feeding whole milk and acidified milk using mob feeders (buckets with multiple nipples) for the first week of life. “This was a huge savings, so we have been doing this ever since,” Andrew says.

Andrew says in order to be successful with these calves as beef animals, health protocols are key. “We were able to skate along the first two years in a brand-new barn, but after that we had a scours wreck,” he says.

Acidified milk is the process of lowering the pH of the milk using an acid, like citric acid, to reduce bacterial growth and reduce spoilage without using refrigeration.

Their operation now uses a scour vaccine in the herd and gives a nasal vaccine to calves under a week old. Until four to five months of age, all of his calves are commingled together. After this age, the calves are sorted into either a replacement or feeder calf group. The feedlot calves are given a modified live vaccine and switched to a feeder diet after they have reach 400 pounds.

In 2020, they converted a previous dairy barn into a slatted floor feeder barn. The facility currently finishes 150 head per year and can hold 60 head at a time. Dairy-beef calves are purchased from other operations that also provide a good start to their calves — “herds that have good management practices such as a herd health protocol, adequate nutrition and good colostrum management,” Andrew says.

The feeders are implanted and weighed every 90 days and are fed a diet containing high moisture corn, grass, mineral with rumensin, roasted beans, soybean oil, barley and corn silage with a gain of approximately four pounds per day. Andrew says, “One of the biggest benefits of doing the 90-day weigh-ins was learning what a finished animal actually looked like. We have also improved our handling capabilities with the dairy herd based on what we have learned with the feedlot.”

Kurtis Moesker, Shylane Holsteins, Perth County, ON

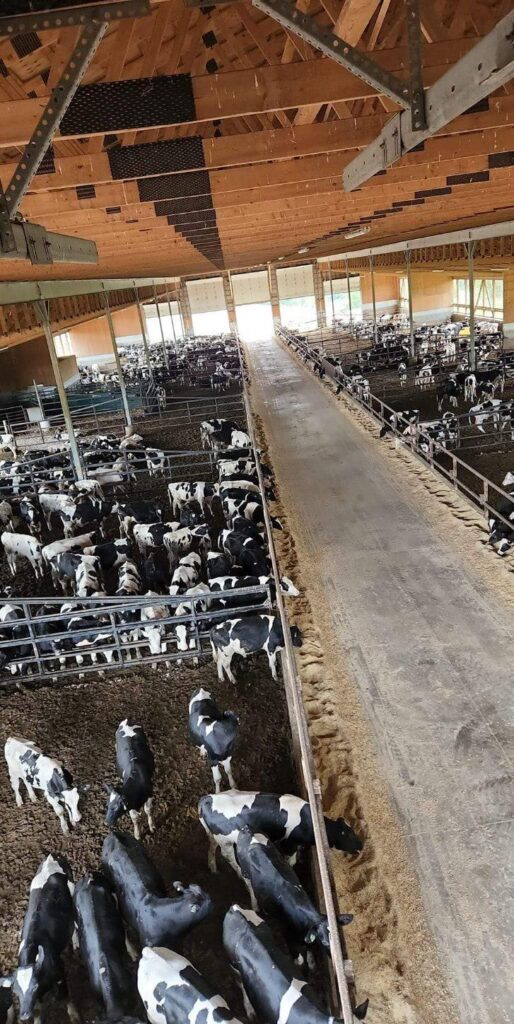

The Perth County region of Ontario is home to 325 dairy farms which produces 11% of the province’s milk supply and a large volume of purebred and dairy-beef calves each year, according to the latest statistics from the Government of Ontario.

Kurtis Moesker started feeding calves from surrounding dairy operations in Perth and Oxford counties on a trial basis in 2014. The operation was already feeding dairy cows and replacement heifers. Kurtis noted, “Nobody wanted to feed dairy calves. We were already set up for feeding cows and heifers, so the calves seemed like a logical next step.”

Kurtis starts 5,000 calves per year, meaning the calves are bottle fed using milk replacer until they are old enough to be weaned off the milk replacer. Out of the 5,000 calves, 60% are raised for veal and the remainder are backgrounded for beef feedlots. The feedlot bound calves are sold once they have reached 800 pounds.

Kurtis starts all calves (both veal and beef) in individual calf hutches. However, as of December 31, 2020, Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Veal Cattle will no longer allow veal calves to be tethered in their individual housing and they must be housed in groups by the time they are eight weeks of age. For Kurtis, this has resulted in major changes for his management practices.

His operation is currently expanding with the construction of a new 2,000-head calf barn and a 3,500-head feeder barn, which will be completed in 2023. In the new calf barn, the calves will be fed individually using a bucket feeder. “Starting the calves is not a glamorous job, there is a lot of manual labour involved,” Kurtis says.

Early calf health management is key for the operation. With the support of his veterinarian, a calf record app was developed to track all the calves by linking their data to their RFID and management tags. The app allows Kurtis and his veterinarian to track the health data of calves coming from the various dairies he purchases from. This has supported the identification of any major health issues that may need to be addressed with a producer and has also allowed Kurtis to make economical decisions with health treatments.

“The app has allowed us to make smart decisions about whether an animal is being treated for the first time or the third time,” he says. “This can help determine whether further treatment should take place.”

Over time, Kurtis has built a good relationship with the nearby feedlots by producing a reliable source of calves that will succeed in a feedlot. “There is an argument for sustainability with the dairy-beef calves,” Kurtis says. “These calves are produced closer to home, which means less trucking and it produces a more efficient [dairy-beef] animal that was going to be produced and fed somewhere. Dairy producers are getting better at selecting their replacements; therefore, there’s going to be more calves to feed.”

Dairy-beef calves are ultimately a by-product of dairy production that can be viewed as an opportunity for the beef sector. These calves are more efficient and resilient than a purebred dairy calf and they are available year-round, but nothing beats a beef calf. However, with proper and strategic management, these dairy-beef calves have a place in the value chain that supports the entire Canadian beef sector.

Le partage ou la réimpression des articles du blog du BCRC est bienvenu et et encouragé. Veuillez mentionner le Conseil de recherche sur les bovins de boucherie, indiquer l’adresse du site web, www.BeefResearch.ca/fr, et nous faire savoir que vous avez choisi de partager l’article en nous envoyant un courriel à l’adresse info@beefresearch.ca.

Vos questions, commentaires et suggestions sont les bienvenus. Contactez-nous directement ou suscitez une discussion publique en publiant vos réflexions ci-dessous.