Seize the Opportunities - Learnings from the Canadian Cow-Calf Cost of Production Network's Future Farm Scenarios

This is the second in a two-part series. Read part one.

About COP Network’s Future Farm Scenarios

The Canadian Cow-Calf Cost of Production Network (COP Network) was launched in 2021, and has since collected production and financial information from over 180 cow-calf producers across Canada. From the discussions and data gleaned from COP Network, 46 benchmark farms were established to represent different regions and production systems.

In addition to benchmarking cost of production, producers in the COP Network discussed possibilities for incremental improvements around productivity, input costs and marketing strategies. Future farm scenarios were then developed for each benchmark farm, simulating the potential cost and revenue of implementing selected practices, such as tightening the calving season, as was discussed in part one of this series.

How are the benchmark farms created?

In 2022, over 70 producers participated in the second year of the COP Network. Increasing weaning weights and pasture management continued to be the two hot topics for the future farm scenarios. In this article, we will look at the results for two future farm scenarios:

- Water system scenario – another practice that could potentially increase weaning weights.

- Rotational grazing with water system and additional funding scenario – an expansion on year-one analysis, considering the potential stacked benefit from a water system with extra weaning weight and funding opportunities.

Water System Scenario

Assumptions

In this scenario the impact of an operation adding a solar-powered water system was modeled.

Studies have shown that calves with cows that drank from troughs gained on average 0.09 lbs per day more than calves with cows that only had direct access to a dugout. Therefore, the major economic benefit in this scenario is the potential extra weight gain (assumed at 0.09 lbs/day) on calves.

The up-front cost of the water system is assumed at $7,500 and an additional $13,000-30,000 if a new well is needed. Maintenance cost is set at $100/year.

It should be noted that the cost of a water system can vary greatly. The cost of a solar-powered water system may range from $4,000-15,000 depending on herd size, lift, and other variables. A new well could range from under $10,000 to over $30,000, depending on specifications such as depth drilled, well diameter, and stainless-steel screens vs. slotted casings. Producers also must follow government requirements for licensing.

Calf prices are kept steady with the baseline level, and price slide due to heavier weaning weight is considered. When weaning weights shift to a heavier category (e.g., from 400-500 lb to 500-600 lb), calf prices ($/lb) shift lower based on the provincial average.

Results

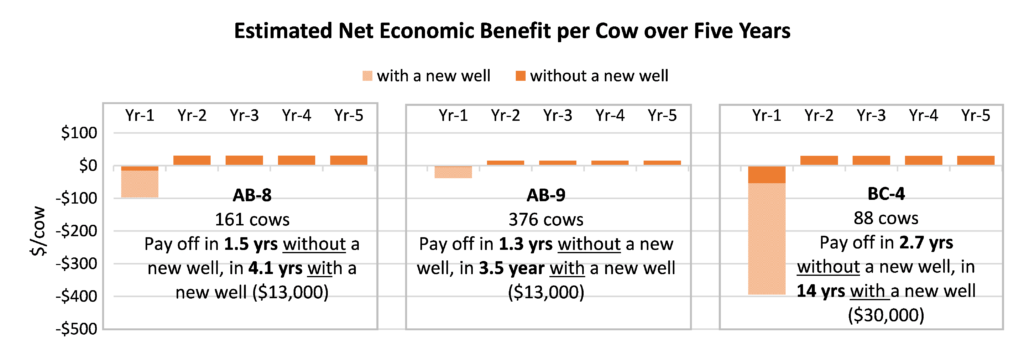

Additional revenue – Weaning weights are estimated to increase by 18 to 20 lbs/calf, bringing an additional $31/cow when weaning weights stay in the same category. For one farm (BC-4) where heifer weaning weight shifts from the 400-500 lb to 500-600 lb category, heifer price/lb drops 4.5% due to price slide. The lower price per pound more than offset the additional weight gain and resulted in a lower revenue gain of $16/cow.

Cost per cow – Up-front costs range from $20-85/cow without a new well, and $55-426/cow with well development. The BC-4 farm has the highest up-front cost, due to the relatively higher cost of a new well, and the smaller herd size.

When herd size increases, unit cost of a water system on a per head basis generally declines and results in a shorter pay-off period with higher net benefits. But it is important to keep in mind that these economies of scale are constrained by the water system’s capacity. If the herd size exceeds the system’s maximum capacity and requires additional equipment, unit cost will increase, and net benefits will decline.

Pay-off period – Without a new well, all three benchmark farms in this scenario can pay-off the up-front investment in 1.3 to 2.7 years, adding $11-21/cow net benefits annually over a five-year period.

When a new well is needed, farms with bigger herds and lower well development costs can pay the investment off in 3.5-4.1 years, with an average of $5/cow net benefit per year over five years. For the farm (BC-4) with a smaller herd and higher well cost, this scenario is not feasible with a 14-year pay-off period and a loss of $55/cow over five years.

AB-8: A benchmark farm in Alberta with 161 cows

AB-9: A benchmark farm in Alberta with 376 cows

BC-4: A benchmark farm in British Columbia with 88 cows

What Does It Mean?

Given the variability in water system costs, it is critical to know the cost of the system that fits the specific operation and pencil out a budget based on current market conditions and targeted pay-off period.

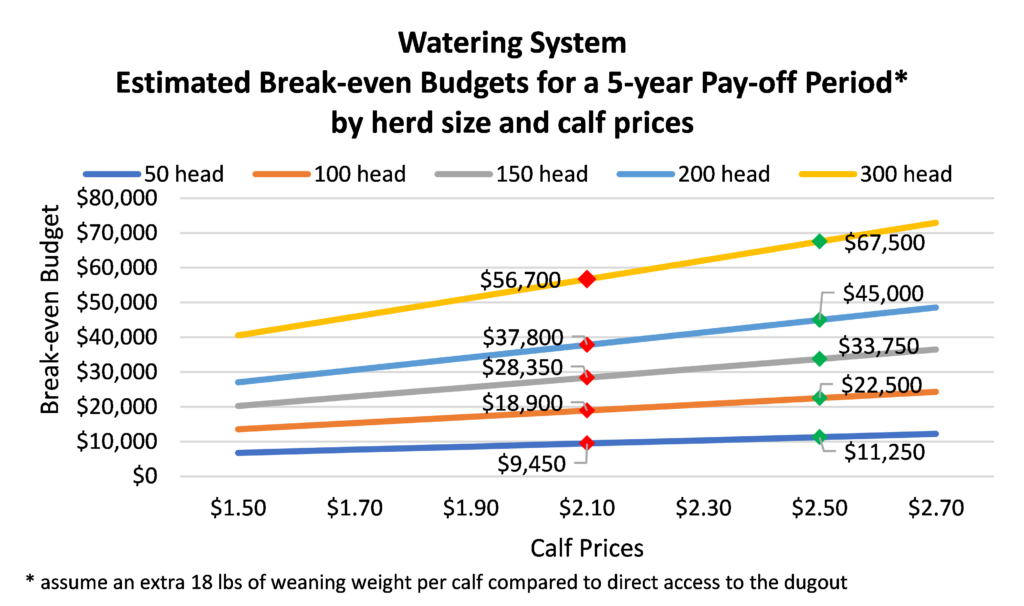

The graph below shows the break-even point for water system costs for a five-year pay-off period, assuming an extra 18 lbs of weaning weight per calf compared to direct access to a dugout.

As shown in the graph, the economics of a water system is affected by cattle prices. When calf prices are high, each additional pound of gain is worth more. Since the second half of 2022, calf prices have been on the rise with tightening cattle supply and strong beef demand. In the fourth quarter of 2022, steer calf prices averaged above $2.60/lb, compared to $2.10/lb a year ago. For a 150-cow operation, when calf prices are $2.10/lb, a system at or under $28,350 is expected to pay off within five years. When calf price increases to $2.50/lb, the budge could increase to $33,750. With that said, producers should keep in mind the potential of lower price per pound on heavier calves.

As the cost advantage of a bigger herd is restricted by the water system’s maximum capacity, choosing a system that best matches water requirements of the herd is also important to reach the optimum utility rate.

Producers can also look for supports from funding programs that share a portion of the up-front costs. Examples of current programs include:

More than just economics.

The economic considerations of developing a water system are important. However, there are other factors to consider such as water source protection, animal health and riparian habitat protection. Learn more about water systems and water quality for beef cattle.

Rotational Grazing with Water System and Additional Funding Scenario

Assumptions

Scenarios on extending the grazing season through rotational grazing were developed for six benchmark farms in 2022. The rotational grazing scenario assumes that a longer grazing season is achieved through improved grazing management, with purchase of a portable electric fencing system in year one to divide pastures into multiple paddocks.

Adding to the scenarios developed in year-one that focus on cost saving from a shorter winter-feeding period, this year’s analysis considered a funding opportunity with the On-Farm Climate Action Fund (OFCAF), and the potential stacked benefit of extra weaning weight from the water system for rotational grazing.

Up-front investment includes a portable electric fencing system as well as a solar-powered water pump and shallow-buried pipeline water system. With the new water system, the potential extra weight gain on calves is assumed at 0.09 lb/day, assuming cattle had direct access to a dugout before.

Assumptions on funding from OFCAF for each benchmark farm are customized based on programs by the associated delivery organization.

Results

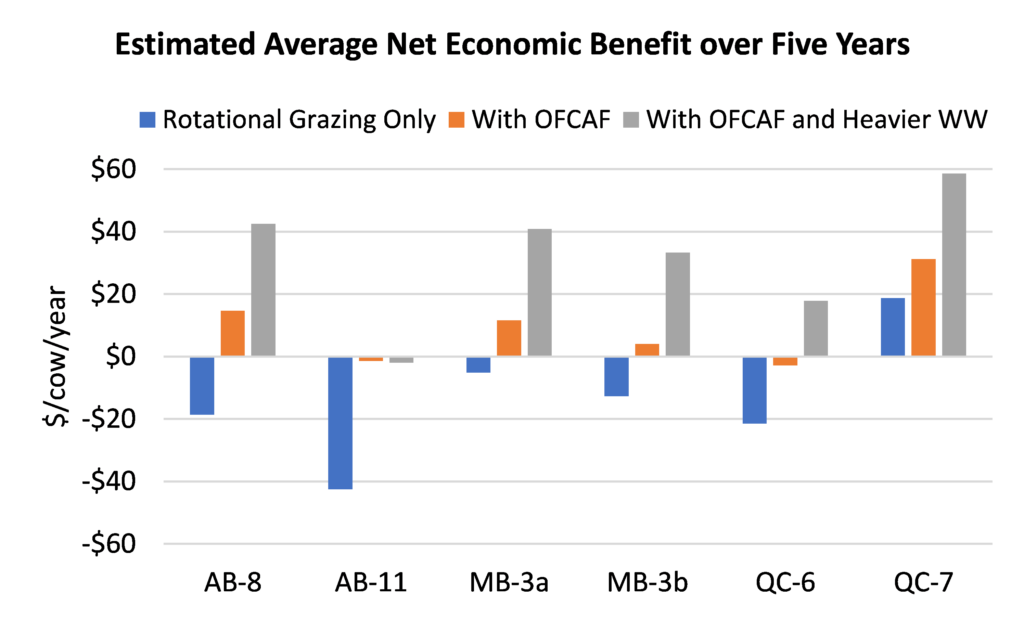

AB-8: In Alberta, with 161 cows, 1,465 acres of grassland

AB-11: In Alberta, with 133 cows, 1,863 acres of grassland

MB-3a: In Manitoba, with 270 cows, 1,040 acres of grassland

MB-3b: In Manitoba, with 270 cows, 1,107 acres of grassland

QC-6: In Quebec, with 150 cows, 156 acres of grassland

QC-7: In Quebec, with 225 cows, 156 acres of grassland

The estimated net benefits of rotational grazing with a shallow buried water pipeline system were generally negative over the five-year period due to the high up-front cost. This was especially true for farms with large pasture areas that required larger investment in the water pipelines, as well as farms with a smaller herd size that increases cost per cow. Farm QC-7 saw positive net benefit with savings on purchased feed as a result of a shorter winter-feeding period.

When OFCAF funding is added to the scenario with a 70-85% reimbursement of eligible costs, up-front costs are reduced significantly, making the scenario feasible for four out of six farms.

If the new water system results in extra weight gain on calves, the stacked benefits of reduced feed costs and extra revenues from heavier weaning weights make the scenario profitable for most of the farms, except AB-11 where weaning weight shifts to a heavier category and results in a lower price per pound.

What Does It Mean?

From an economic standpoint, the feasibility of a rotational grazing system depends on the amount of up-front investment, herd size, potential cost savings and revenue gains as well as capital and labour availability of the farm.

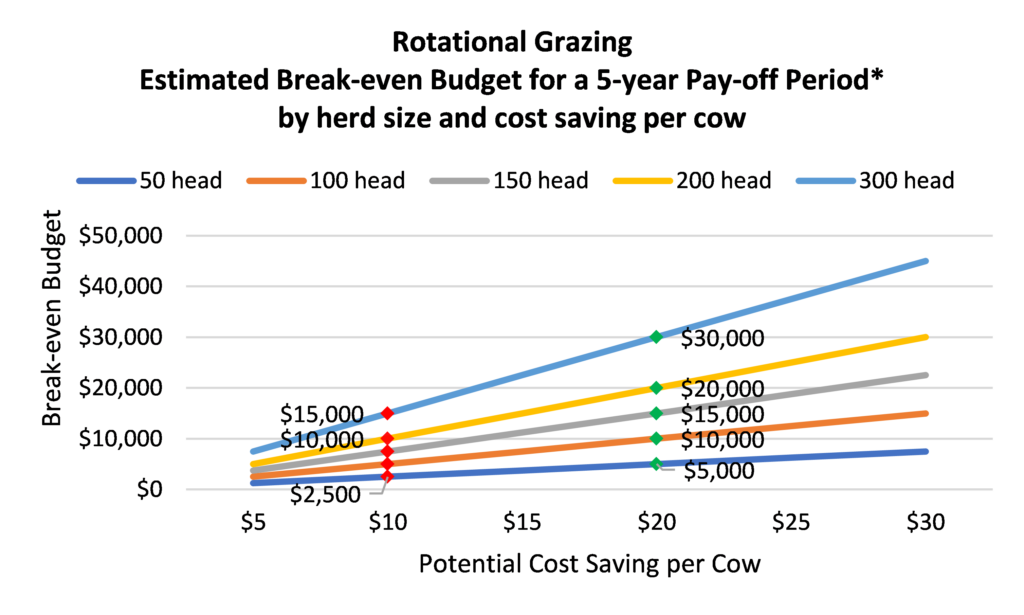

The graph below shows the feasible up-front investment for different herd sizes and cost saving levels. For example, if a 200-cow operation projects to save $20/cow with an extended grazing season, an up-front investment of $20,000 would be feasible for a 5-year pay-off period. As herd size and cost savings from an extended grazing season increases, the budget increases.

Operations that do not have a water system can see extra benefit in this scenario with extra weaning weight.

Funding opportunities, such as OFCAF, can help producers finance the development and implementation of rotational grazing. It should be noted that each province has a different agency that is administering the rotational grazing funding and their coverage, requirements and application process differs. It is important for producers to contact their local delivery agent for details and assistance in developing their plan and application.

LEARN MORE

- Canadian Cow-calf Cost of Production Network (Canfax Research Services webpage)

- Cost, Profits and What If? The Canadian Cow-Calf Cost of Production Network (BCRC webinar)

- Rotational Grazing Improves Stocking Capacity and Ranch Profitability (South Dakota State University Extension post)

- Grazing Management (BCRC topic page)

- Fencing & Water Infrastructure on Pasture (Pasture 101 webpage)

- What Does the On-Farm Climate Action Fund Mean for Rotational Grazing? (Canadian Cattlemen magazine article)

Le partage ou la réimpression des articles du blog du BCRC est bienvenu et et encouragé. Veuillez mentionner le Conseil de recherche sur les bovins de boucherie, indiquer l’adresse du site web, www.BeefResearch.ca/fr, et nous faire savoir que vous avez choisi de partager l’article en nous envoyant un courriel à l’adresse info@beefresearch.ca.

Vos questions, commentaires et suggestions sont les bienvenus. Contactez-nous directement ou suscitez une discussion publique en publiant vos réflexions ci-dessous.