Information is Key to Fine Tuning On-Farm Breeding Program

Remarque : cette page web n’est actuellement disponible qu’en anglais.

Les Johnston has long subscribed to the beef management theory, “the more you know about your cattle the more it pays.” Whether the south-Saskatchewan beef producer is raising purebred Simmental bulls for a breeding market, or commercial cross-bred steers for the packing plant, he wants to know how those animals perform.

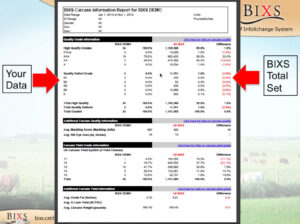

Being able to receive a steady flow of carcass data on cull livestock or finished commercial steers through the Beef InfoXchange System (BIXS) is a valuable confirmation of whether his breeding program is on the right track.

Johnston, who owns Nisku Land and Cattle Inc. near Fillmore, Sask has farmed between both the purebred and commercial cattle industries for the past 40 years. He focused on purebred Simmental cattle for many years, when the BSE crisis developed in early 2000s then switched to producing and finishing mostly commercial cattle, and although he has been downsizing in the past year, still runs a smaller purebred as well as commercial beef herd.

But whether it is the commercial or purebred side he has always been interested in learning as much about cattle performance as he could.

“Basically it comes down to you can’t fix what you don’t know,” says Johnston. “We have always been interested in seeing carcass data even before BIXS came along, but now it becomes a much easier process. “

On the purebred side he began using ultrasound technology to measure marbling on replacement cattle in 1990s. “We were really impressed where the Simmental breed was headed, but because the registry hadn’t been developed yet, we couldn’t identify the genetics we needed. We actually had to turn to Red and Black Angus to find the genetics to produce the carcass quality we wanted.”

In the early 2000s he began DNA testing bulls, and continues with that today. The DNA testing confirms genetic lines in the purebred herd and also is a check against ultrasound readings of carcass quality factors. An ultrasound reading provides a measure of ribeye area, marbling and back fat thickness on a particular animal. Depending on the amount of information the producer wants, a DNA test, made from a hair sample, can also reveal its potential for ribeye, marbling and backfat as well as carcass grade, yield grade, and tenderness. The combination of ultrasound and a DNA test provides relatively solid assurance of the traits that breeding animal will pass along to its offspring. And if the producer wants more information about the animal’s potential the DNA test can also provide a score for average daily gain, docility (behavior), fertility, calving ease, feeding efficiency and longevity.

With BSE derailing the Canadian beef market in 2003, Johnston began producing more commercial cattle and finishing them himself, running about 240 head.

“We actually began doing more on the commercial side before the BSE crisis,” says Johnston. “But once BSE hit we stepped up our commercial program and began to retain ownership of the steers. I believe you can always make money on good cattle and I had enough data on this herd that told me if I finished these cattle properly I could still make a few pennies on each one, or at least not lose my shirt,” says Johnston. “And that approach came true— we were still able to make a few dollars on these cattle.” Relying on the genetic potential of his cattle, Johnston was consistently able to finish and market steers with a good mix of AAA and AA carcass grading for a price premium.

Whether it was on younger purebred cattle that were culled, or on his own finished steers, he always sought out carcass data from the packing plant to guide his breeding program.

“The carcass data from the packing plant was able to tell us generally how the herd was performing, but it wasn’t able to narrow it down to the individual genetics of an animal,” he says. “That is where BIXS is an improved information tool. We are able to get carcass data specific to each tagged animal. We have 11 breeding pastures on this farm, so with that I.D. number I can know with almost certainty the dam and the sire of that animal, and then evaluate how those genetics are performing.” Johnston says by being able to connect the carcass quality information of an individual animal with its sire and dam he can decide which bulls are producing the most desirable carcass traits in steers and select accordingly. “With our breeding management and record keeping system, once I get that carcass data back from the packing plant and it is associated with an RFID number, I can easily check the records and know exactly the sire and dam of that animal. And if for some reason that sire and dam combination isn’t producing a calf that produces a desirable carcass it doesn’t mean I have to cull them. I can just look at the genetic information I have for the herd and perhaps just put that cow with a different bull next year to improve the traits in the next calf.”

While Johnston, in the past couple years, is no longer retaining ownership of steers, he can still receive carcass data reports on his cattle. Calves marketed last fall, for example, are being backgrounded at a feedyard in Saskatchewan and then will be finished at a feedlot in Ontario. If finished cattle are processed at the Cargill plant in Ontario “those carcass data reports will eventually arrive back at the computer in my office,” he says.

When he was marketing his own steers Johnston was selling them on the grid. That required that at least 60 per cent of the steers grade AAA, with the rest hopefully producing AA carcasses. “And really it is the AAs where we made the most money,” he says.

Johnston says when marketing on the grid he found the difference in price between a good AA animal and AAA could be very minor. “Unless you can negotiate a very good premium for cattle sold on the grid, a AA carcass with high lean meat yield can often provide as good a return as anything. The goal is produce a AAA, but at the same time maintain a lean meat yield of 59 per cent or higher.”

The grid maximum at the time sought a hot carcass weight no heavier than 925 pounds, so he targeted his program to produce steers achieving an 840 to 900 pound carcass weight. And his breeding program selection over the years, has been on target — selecting bulls that produce the proper sized animal with desirable carcass traits. “In all the time we have been doing this before and now with BIXS we have only had one single A animal,” he says.

Johnston says the potential information flow that BIXS offers across the production chain is valuable information to any producer who is serious about fine tuning their breeding program to produce quality cattle for the market place.

“And it reduces the risk,” he says. “You can finish and market your own cattle to get carcass data, but then you are carrying all the risk of feeding those cattle. With BIXS, any producer can produce a nice bunch of calves, sell them to a feedyard and then in a few months get the carcass data delivered to them. It takes a bit of learning to know how to read and understand a carcass report, but it can be an important tool in guiding your breeding program.

Johnston admits that genetic selection is only part of the equation in producing a market animal with top carcass quality — the feedlot feeding program also plays an important role too. “But genetics is most important part of the equation,” he says. “As one of the leading beef industry experts, Charlie Gracey, says ‘you can’t make a poor carcass better, if the genetics aren’t there. But, with poor management you can certainly wreck a good carcass. ‘ As producers, I believe it is important to know who is feeding your cattle and how they are feeding them,” he says. “I do my best to find out where my calves go and follow up with the feeder if I can. But at the same time, most of these feedyards are doing their best to optimize their rates of gain and produce a quality animal. It is in their best interest to market good quality cattle. And if the genetics are there to begin with, those cattle will finish properly.”

“One important caution is not to let your herd get too far to one extreme or the other because then it becomes too hard to bring it back. If the reports start to show that animals are getting too big, for example, bring different genetics in to your breeding program. You may have to swallow your ego and buy a different breed altogether, but it will keep those cattle in the range that the market wants.”

App for BIXS

Recognizing the importance of having more information to make better decisions, is one reason an Alberta veterinary clinic has developed a mobile app to help clients connect with BIXS as a value added service.

The app, developed to work with all Android phones, is intended to make it easier for producers to enter calving and other relevant information onto the BIXS system, says Dr. Mike Jelinski with Veterinary Agri-Health Services Ltd. in Airdie, just north of Calgary. It is available to clients for a nominal fee.

“We knew that certainly some of our clients were interested in having access to carcass data, and we felt by developing this app it would make it easier for them to access BIXS and be a value added service,” says Jelinski.

Launched in 2014, the veterinary service had about 30 clients sign up for the app last year and more are expected in 2015. Producers have the app on their cell phone or tablet and can enter as much information as they want into BIXS. The key pieces of information along with CCIA tag number are date of birth (birth date method — either actual or calving start date) and sex of calf. But, the app can be used to enter a wide range of information including notes on calving difficulty and any treatment protocols.

“Along with the basics they can enter as much information as they want,” says Jelinski. “And they can do it right there in field or later if it is more convenient. And then with a couple of simple steps that information can be sent directly to BIXS.”

Recognizing that BIXS is really just getting established as an a conduit for information back and forth through the beef production chain, Jelinski says they offered the app as a way to get producers familiar with providing information to BIXS.

As the flow of information matures, he says there will hopefully be value in helping producers better manage or fine-tune their breeding programs, and search out market opportunities. “It may be of value to go to an auction mart or feedlot with records that include a vaccination certificate on all your calves,” he says. “And with a record of animal health protocols there may be more opportunity to access markets looking for natural beef, or hormone free, or antibiotic free cattle. So the app is a value added service to help clients get on board early and become familiar with BIXS, and the process of collecting this information.”

Related: Carcass data important for seedstock development research

Click here to subscribe to the BCRC Blog and receive email notifications when new content is posted.

The sharing or reprinting of BCRC Blog articles is welcome and encouraged. Please provide acknowledgement to the Beef Cattle Research Council, list the website address, www.BeefResearch.ca, and let us know you chose to share the article by emailing us at info@beefresearch.ca.

We welcome your questions, comments and suggestions. Contact us directly or generate public discussion by posting your thoughts below.