Narrowing in on Johne’s Disease

Remarque : cette page web n’est actuellement disponible qu’en anglais.

This article written by Dr. Reynold Bergen, BCRC Science Director, originally appeared in the February 2019 issue of Canadian Cattlemen magazine and is reprinted on the BCRC Blog with permission of the publisher.

Johne’s disease is caused by a bacterium (Mycobacterium avium paratuberculosis, or MAP) that was discovered in 1895 by a heavily bearded, bespectacled bacteriologist from Dresden named Henrich Albert Johne. When a cow develops persistent, watery, smelly hosepipe diarrhea, and progressively loses weight and body condition even though her appetite is normal and she isn’t running a temperature, she may have Johne’s disease. But it can be hard to know for sure.

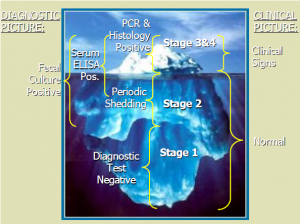

Young calves, which are more susceptible to infection than older animals, are often infected with MAP through colostrum, milk or manure. The animal will look perfectly normal, while silently shedding MAP in its own colostrum, milk or manure for a few years before full-blown signs of disease appear. As a result, Johne’s disease is often compared to an iceberg – by the time you see an obviously sick animal, there will be a much larger hidden population of MAP-infected cattle that haven’t become sick yet.

Vaccines against Johne’s disease reduce shedding but don’t prevent MAP infection. There are no antibiotics that effectively treat Johne’s disease. Current diagnostic tests can accurately identify most cattle shedding high amounts of MAP (like the cow described at the start) but usually fail to detect cattle shedding low amounts of MAP (these misidentified animals are called false negatives). This means that newly infected animals appear faster than the carriers can be identified and culled, so testing and culling is playing a never-ending game of catch-up. Meanwhile, the costs of Johne’s disease add up due to earlier culling, poorer reproductive performance, lighter weaning weights, and lower values for breeding stock sold from herds that are known to be infected.

A 2013-18 Beef Science Cluster project led by the University of Guelph’s Lucy Mutharia made significant progress towards a better diagnostic test to accurately identify MAP-infected animals in the very early stages of disease (“Novel secreted antigens of Mycobacterium paratuberculosis as serodiagnostic biomarkers for Johne’s disease in cattle”, Clinical and Vaccine Immunology 20:1783-1791).

What they did:

Three different MAP strains were isolated and cultured from fecal samples collected from dairy herds throughout Ontario. Proteins secreted by MAP bacteria (the proteins that the animal’s immune system is most likely to respond to) were isolated and purified. These proteins were then tested using serum collected from 25 cows known to be infected and shedding high levels of MAP, low levels of MAP or no MAP at all, as well as 10 cows and calves from a Johne’s-free herd.

What they learned:

A total of 163 antigenic proteins were identified from the three MAP strains, 76 of which had never been discovered before. A number of these proteins specifically reacted with serum samples collected from MAP-infected cows, suggesting that the cow’s immune systems were recognizing them as foreign antigens. The new antigens discovered in this study reacted most strongly with cows that were shedding high levels of MAP and tested positive using commercial diagnostic tests. However, they also identified animals that tested negative using commercial diagnostic tests because they were shedding so little MAP (so fewer false negatives). Equally importantly, these new antigens did not identify any false positives among the cows or calves from a Johne’s-free herd. These new antigens were not found in other species of Mycobacteria that are commonly found in the environment. This is a good thing, because commercial diagnostic tests need to add extra steps to prevent environmental Mycobacteria from producing false-positive results.

What it means:

If additional validation on larger numbers of high shedding, low-shedding and MAP-free cattle give the same results, we may be close to a test that can accurately identify cattle much, much sooner. This will greatly aid efforts to deal with Johne’s disease.

These researchers are collaborating with the University of Saskatchewan’s Vaccine and Infectious Diseases Institute to further refine these tests, and to study whether they can detect MAP antibodies in more easily-collected fecal samples. Down the line, additional work looking at the detailed immune response in the intestine of newly infected calves done as part of the Beef Cluster study may also contribute to an effective vaccine to protect against Johne’s disease.

In the meantime, you can help protect your herd from Johne’s (and many other calfhood diseases) by calving on a well-drained pasture (if possible) to keep the herd spread out, ensure shelter and bedding are adequate so that calves aren’t nursing filthy udders, not “borrowing” colostrum from a dairy or neighbor, and not buying bargain breeding stock with unknown disease status at the auction market .

Protect your herd from Johne’s by calving on a well-drained pasture to keep the herd spread out, ensure shelter and bedding are adequate so that calves aren’t nursing filthy udders, not “borrowing” colostrum from a dairy or neighbor, and not buying bargain breeding stock with unknown disease status at the auction market.

The Canadian Beef Cattle Check-Off has increased from $1 to $2.50 per head in most provinces, with approximately 75 cents allocated to the Beef Cattle Research Council. Canada’s National Beef Strategy outlined why the Check-Off increase was needed, and how it would be invested. One goal laid out in the strategy was a 15% increase in production efficiencies, partly through research and development to improve diagnostic tests for animal health and welfare issues.

The Beef Research Cluster is funded by the Canadian Beef Cattle Check-Off and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada with additional contributions from provincial beef industry groups and governments to advance research and technology transfer supporting the Canadian beef industry’s vision to be recognized as a preferred supplier of healthy, high quality beef, cattle and genetics.

Click here to subscribe to the BCRC Blog and receive email notifications when new content is posted.

The sharing or reprinting of BCRC Blog articles is typically welcome and encouraged, however this article requires permission of the original publisher.

We welcome your questions, comments and suggestions. Contact us directly or generate public discussion by posting your thoughts below.