Lorsque l’on ne connaît pas la qualité des aliments pour animaux d’une exploitation, le maintien de la santé et du bien-être des animaux peut s’avérer beaucoup plus difficile. L’évaluation visuelle des aliments pour animaux n’est pas suffisamment précise pour déterminer la qualité et peut conduire à une sous-alimentation des vaches et à une perte d’état corporel, ou à un gaspillage d’argent pour des suppléments coûteux qui ne sont pas nécessaires.

SUR CETTE PAGE :

- Pourquoi tester les aliments ?

- Un outil pour évaluer les résultats des tests sur les aliments pour animaux

- Prélèvement d’échantillons d’aliments pour animaux

- Pour quels éléments devrais-je effectuer des tests ?

- Un outil pour évaluer les résultats des tests sur les aliments pour animaux

- Spectroscopie de réflectance dans le proche infrarouge (NIRS)

- Répondre aux besoins en nutriments du bétail

- Interpréter les résultats de laboratoire

- Prévenir les problèmes

- Qu’en est-il de l’eau ?

- Formuler des rations

- Intéressé par les tests sur les aliments pour animaux ? Quelle est la prochaine étape ?

- Un outil d’évaluation de la valeur économique des aliments pour animaux basé sur la teneur en éléments nutritifs

- Télécharger les versions Excel des calculateurs

Il est essentiel de comprendre la qualité des aliments donnés dans une exploitation de bovins de boucherie pour préserver la santé et le bien-être des animaux. L’évaluation visuelle des aliments n’est pas un moyen précis d’évaluer la qualité et peut conduire à une sous-alimentation des vaches et à une perte d’état corporel ou à des dépenses excessives pour des suppléments coûteux qui ne sont pas nécessaires. Il est recommandé aux producteurs de tester les aliments avant de les distribuer afin de s’assurer que les besoins nutritionnels du bétail seront satisfaits.

| Points clés |

|---|

| Les tests sur les aliments peuvent aider les producteurs à identifier les problèmes potentiels qui pourraient résulter de déséquilibres nutritionnels. |

| Il est crucial de prélever un échantillon d’aliment représentatif de l’ingrédient ou des ingrédients de l’aliment que vous testez. |

| Les échantillons devraient être prélevés aussi près que possible de la période d’alimentation ou de vente, tout en laissant suffisamment de temps pour que les résultats reviennent du laboratoire. |

| Les résultats de laboratoire sont généralement rapportés à la fois sur la base de la “matière sèche ”et “tel que nourri”. La matière sèche (MS) fait référence au contenu nutritionnel sans eau de l’échantillon. Les rations doivent toujours être formulées sur la base de la MS. |

| La plupart des laboratoires fournissent des informations de base sur la teneur en eau, les protéines, l’énergie, les nutriments digestibles totaux, les fibres et certaines vitamines et minéraux. Des tests plus spécialisés peuvent inclure des résultats concernant le pH, l’azote insoluble au détergent acide (AIDA), les nitrates, les toxines, la valeur alimentaire relative (VAR) et d’autres paramètres. |

| Les oligo-éléments, en particulier le cuivre, le zinc, et le manganèse, sont importants pour la reproduction, la santé et la croissance d’un animal et nécessitent presque toujours unesupplémentation. |

| Dans la plupart des cas, il est recommandé de donner des suppléments de minéraux tout au long de l’année. |

| Les tests de qualité de l’eau des bovins sont particulièrement importants en période de sécheresse, lorsque les minéraux et les nutriments peuvent se concentrer en raison de la baisse du niveau des nappes phréatiques des eaux de surface ou souterraines, ou de l’évaporation dans les étangs de bovins. |

| Une fois que les résultats des tests sur les aliments sont disponibles, les producteurs peuvent formuler une ration appropriée pour leurs bovins en faisant appel aux services d’un nutritionniste qualifié, à l’assistance du personnel de vulgarisation agricole ou à un logiciel tel que CowBytes |

Pourquoi devrais-je tester les aliments ?

- Éviter les problèmes de production sournois, tels que les faibles gains ou la réduction de la conception, causés par des carences ou des excès en minéraux ou en nutriments;

- Prévenir ou identifier les problèmes potentiellement dévastateurs dus à la toxicité des mycotoxines, des nitrates, des sulfates ou d’autres minéraux ou nutriments;

- Développer des rations appropriées qui répondent aux besoins nutritionnels de leurs bovins de boucherie;

- Identifier les lacunes nutritionnelles qui peuvent nécessiter une supplémentation;

- Économiser l’alimentation et profiter des opportunités d’inclure des ingrédients diversifiés dans la mesure du possible;

- Fixer avec précision le prix des aliments pour animaux à l’achat ou à la vente.

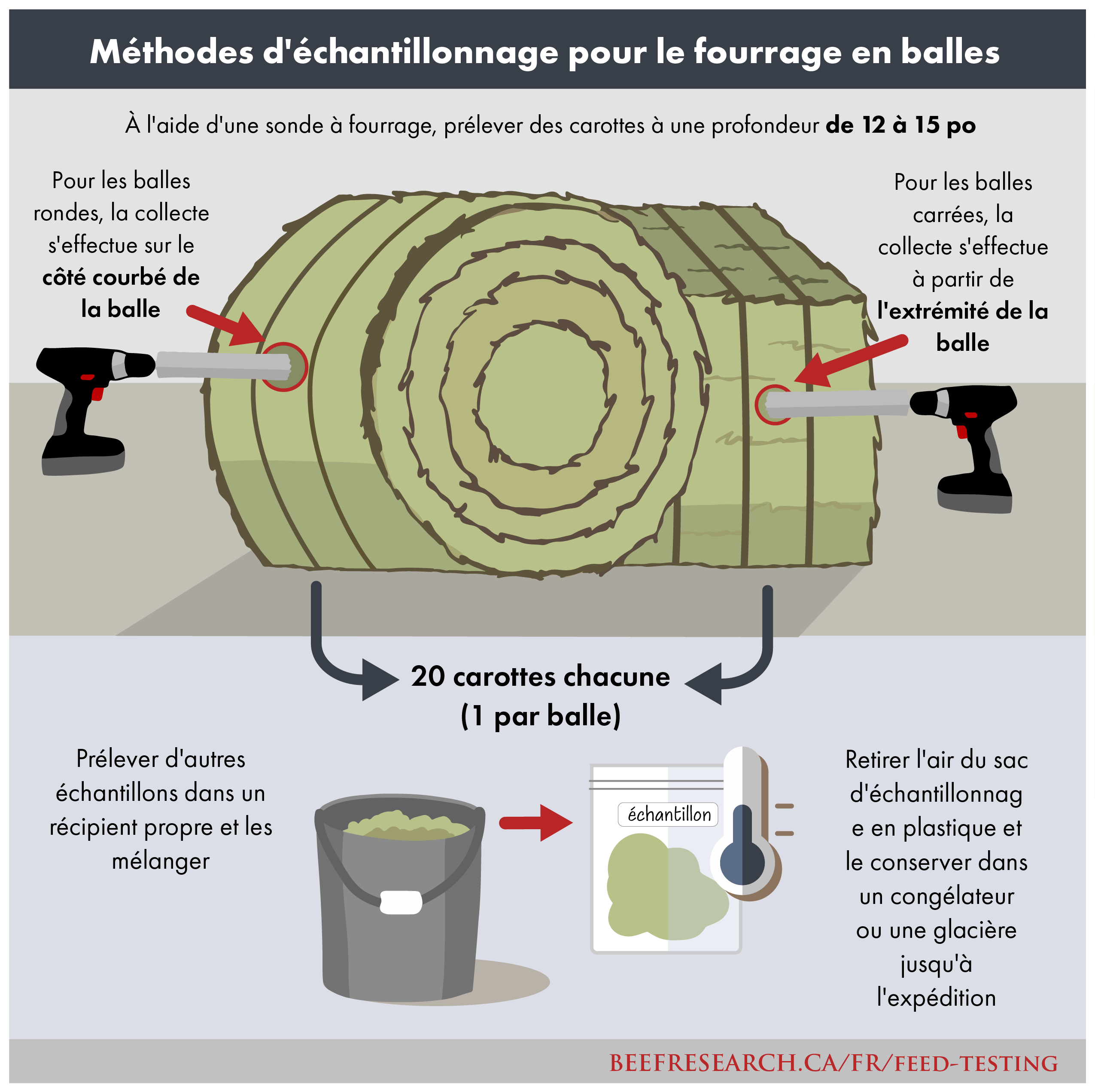

- Utiliser une sonde à fourrage pour la collecte des échantillons.

- Prélever des carottes sur 20 balles pour chaque échantillon que vous souhaitez soumettre.

- Échantillonner les balles carrées et rondes à une profondeur de 12-15 pouces.

- Les balles rondes doivent être échantillonnées à partir des côtés arrondis.

- Les balles carrées doivent être échantillonnées à partir de l’extrémité.

- Combinez les carottes d’échantillonnage, mélangez-les et scellez-les dans un sac en plastique propre.

- Conserver dans un endroit frais et sec jusqu’à l’expédition.

- Prélever des échantillons d’une main à au moins 10 endroits différents autour de la pile ou du tas.

- Échantillonner les piles de foin ou le foin haché à une profondeur de 18 pouces.

- Prélever environ 2 gallons de fourrage moulu.

- Placer les échantillons dans un récipient propre et bien mélanger.

- Prélever un sous-échantillon et l’enfermer dans un sac en plastique propre.

- Conserver dans un endroit frais et sec jusqu’à l’expédition.

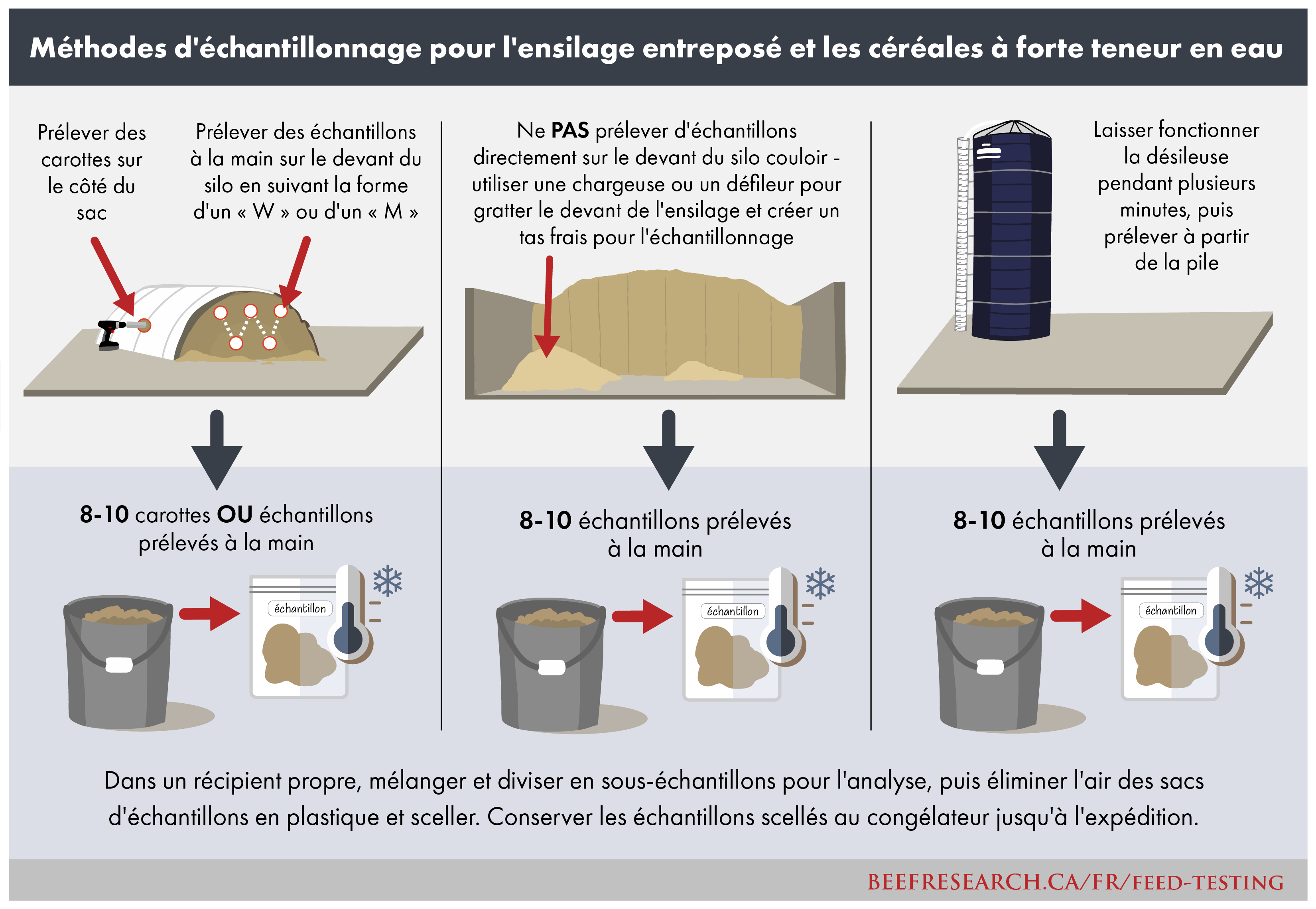

- Il n’est pas recommandé de prélever des échantillons en surface avec la main lors de l’échantillonnage de l’ensilage dans un silo-couloir, en raison de problèmes de sécurité potentiels.

- À l’aide d’une benne chargeuse ou d’un défileur d’ensilage, gratter soigneusement la face du silo pour créer un tas d’ensilage sur le sol du silo. Ceci peut être fait en même temps que l’alimentation du jour pour économiser du temps sur le fonctionnement de l’équipement;

- Prélever cinq à huit échantillons d’une main dans le tas, les combiner et bien les mélanger;

- Prélever un échantillon représentatif et le placer dans un sac en plastique propre;

- Enlever l’air du sac et le conserver au congélateur ou dans un endroit frais jusqu’à l’expédition.

- Éviter l’ensilage vieux ou avarié;

- Prélever 8 à 10 échantillons d’une main sur la surface en suivant la forme d’un “W” ou d’un “M”, ou 3 à 5 échantillons de carottes le long du sac ;

- Combiner tous les échantillons et bien mélanger;

- Prélever un échantillon représentatif et le placer dans un sac en plastique propre;

- Enlever l’air du sac et le stocker immédiatement dans un congélateur ou un autre endroit frais jusqu’à l’expédition.

- Ne pas prélever d’échantillons du matériel avarié au sommet du silo ; enlever 2 à 3 pieds avant de prélever l’échantillon;

- À partir de la désileuse, prélever 1 à 2 livres d’ensilage;

- Bien mélanger l’ensilage et prélever un sous-échantillon;

- Enlever l’air du sac et le stocker immédiatement dans un congélateur ou un autre endroit froid jusqu’à l’expédition.

- Utiliser un seau de 20 litres avec un couvercle;

- Prélever 2 à 3 petites poignées de chacun des deux ou trois chargements;

- Garder le couvercle du seau fermé après l’ajout des échantillons pour conserver l’humidité;

- Une fois le silo-couloir, le sac ou le silo vertical rempli, mélanger les échantillons dans le seau et prélever un sous-échantillon représentatif;

- Envoyer immédiatement l’échantillon pour les tests;

- Utiliser une sonde à fourrage pour la collecte des échantillons;

- Prélever des carottes sur 20 balles pour chaque échantillon que vous souhaitez soumettre;

- Recouvrir le trou avec du ruban adhésif après le prélèvement de l’échantillon;

- Placer l’échantillon de carotte dans un seau propre et bien mélanger;

- Transférer les échantillons de carottes mélangés dans un sac en plastique propre;

- Placer au congélateur ou dans un autre endroit frais jusqu’à l’expédition.

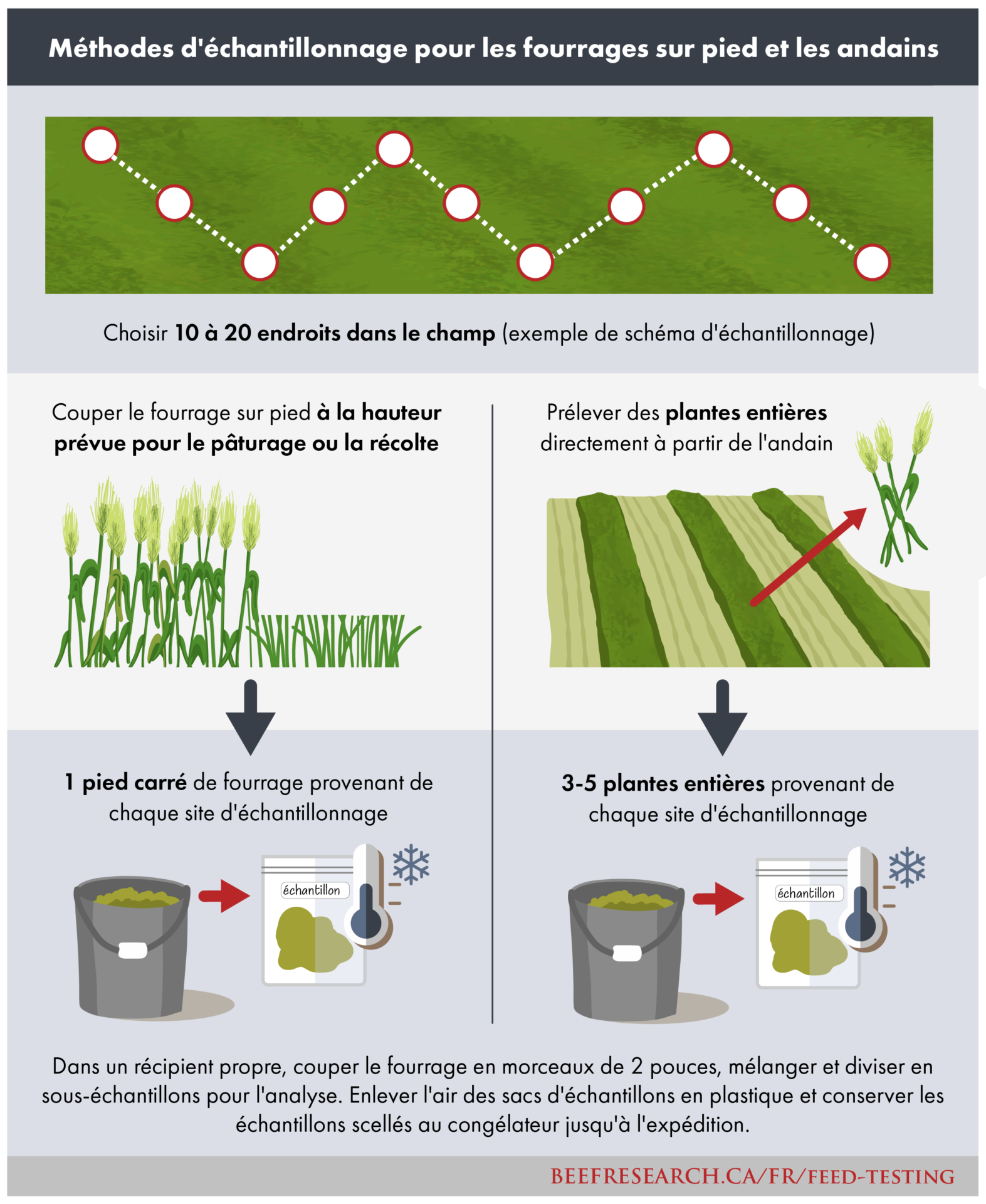

- Choisir un minimum de 8 emplacements pour l’échantillonnage;

- Couper le fourrage de chaque emplacement choisi dans une zone d’un mètre carré;

- Laisser 4 pouces de tige;

- Pour les plantes déjà présentes dans les andains, prélever 3 à 5 plantes entières à 20 endroits dans le champ;

- Couper soigneusement le fourrage en morceaux de 1 à 2 pouces et les placer dans un sac en plastique propre;

- Conserver immédiatement au congélateur ou dans un autre endroit frais jusqu’à l’expédition.

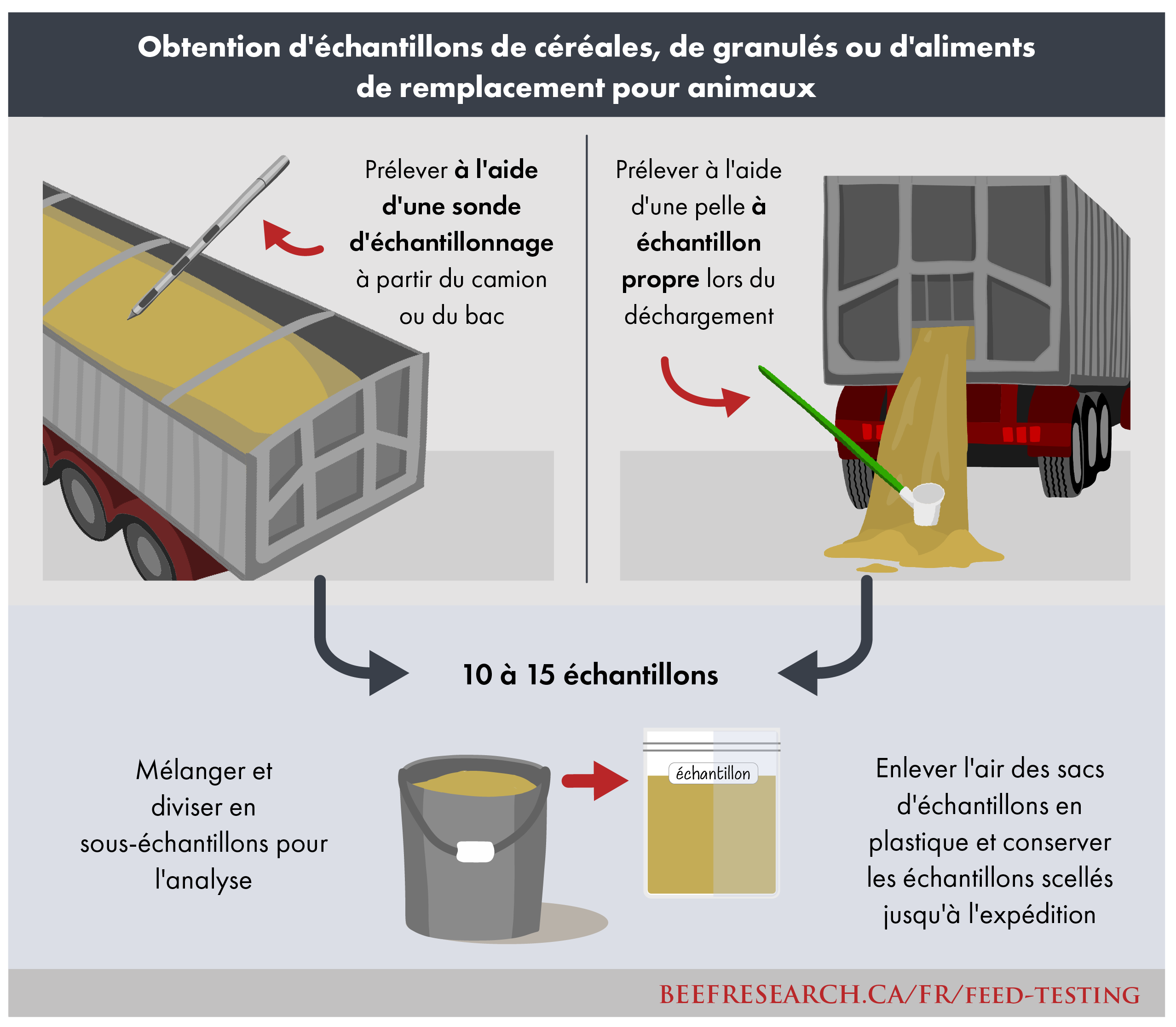

- Prélever 10 à 15 échantillons pendant le déchargement du produit;

- Bien mélanger les échantillons ensemble;

- Placer un sous-échantillon représentatif dans un sac en plastique propre;

- Conserver dans un endroit frais et sec jusqu’à l’expédition.

- Utiliser une sonde à grains;

- Prélever des échantillons dans 10 à 15 zones différentes de la cellule;

- Bien mélanger les échantillons ensemble;

- Placer un sous-échantillon représentatif dans un sac en plastique propre;

- Conserver dans un endroit frais et sec jusqu’à l’expédition.

- Situation alimentaire (c’est-à-dire pâturage ou alimentation hivernale);

- Espèces végétales;

- Gestion des fourrages;

- Stade de croissance des végétaux;

- Type de sol et zone;

- Conditions météorologiques;

- Réserve en eau disponible et qualité de l’eau.

- Évaluez vos ressources en aliments. pour animaux. Quels types d’aliments envisagez-vous d’utiliser et quels tests conviennent le mieux à vos types de fourrage ?

- Disposez-vous des outils adéquats, notamment d’une sonde d’échantillonnage du fourrage ? Les échantillons prélevés sont-ils représentatifs de vos types d’aliments ?

- Évaluez vos objectifs en matière de tests d’alimentation. Qu’est-ce qui vous motive ? Comment comptez-vous utiliser les résultats ? Avez-vous contacté un nutritionniste, un agrologue ou un vétérinaire avec qui vous pouvez travailler pour interpréter les analyses ?

- Y a-t-il des problèmes potentiels que vous souhaitez éviter ? Par exemple, êtes-vous préoccupé par le risque de mycotoxines dans l’orge ou de nitrates dans une culture qui a vécu un stress ? Avez-vous eu, vous ou vos voisins, des problèmes particuliers dans le passé ?

- Comprenez les réalités des résultats potentiels et étudiez les options qui s’offrent à vous en matière d’alimentation. Si vos aliments sont de mauvaise qualité ou contiennent des toxines potentiellement dangereuses, comment pouvez-vous les utiliser au mieux ? Avez-vous l’habitude d’utiliser des aliments de mauvaise qualité ? Connaissez-vous les risques liés à l’utilisation d’aliments potentiellement problématiques ?

- Cet outil évalue uniquement la valeur des aliments par rapport aux aliments de référence et aux deux composants nutritifs sélectionnés. Il ne tient pas compte des autres éléments nutritifs qui influencent la valeur ou qui sont nécessaires à une ration équilibrée et ne calcule pas le coût réel de l’aliment.

- Pour vous assurer que tous les besoins en nutriments sont satisfaits, demandez à un nutritionniste de formuler votre ration ou utilisez un logiciel d’équilibrage des rations.

- Pour obtenir les meilleurs résultats, utilisez des informations provenant d’analyses d’aliments réelles et non des estimations approximatives.

- Pour obtenir les meilleurs résultats, comparez des aliments qui répondent à des besoins nutritionnels similaires. Exemple : bien que le foin de légumineuses ait un pourcentage élevé de PB par rapport au foin de graminées, il est préférable de le considérer comme une source d’énergie à base de fourrage. Des aliments comme le tourteau de canola ou les drêches de distillerie peuvent être des sources de PB plus rentables. Ils ont chacun un rôle différent à jouer dans l’alimentation des bovins.

Les tests sur les aliments sont un outil important pour la gestion des aliments. Les webinaires suivants abordent les principaux défis et opportunités liés aux tests sur les aliments, la signification des résultats et les raisons pour lesquelles ils peuvent être un outil clé pour votre exploitation.

Vidéo : Test d’aliments – Pourquoi le faire ? offert en anglais seulement

Prélèvement d’échantillons d’aliments pour animaux

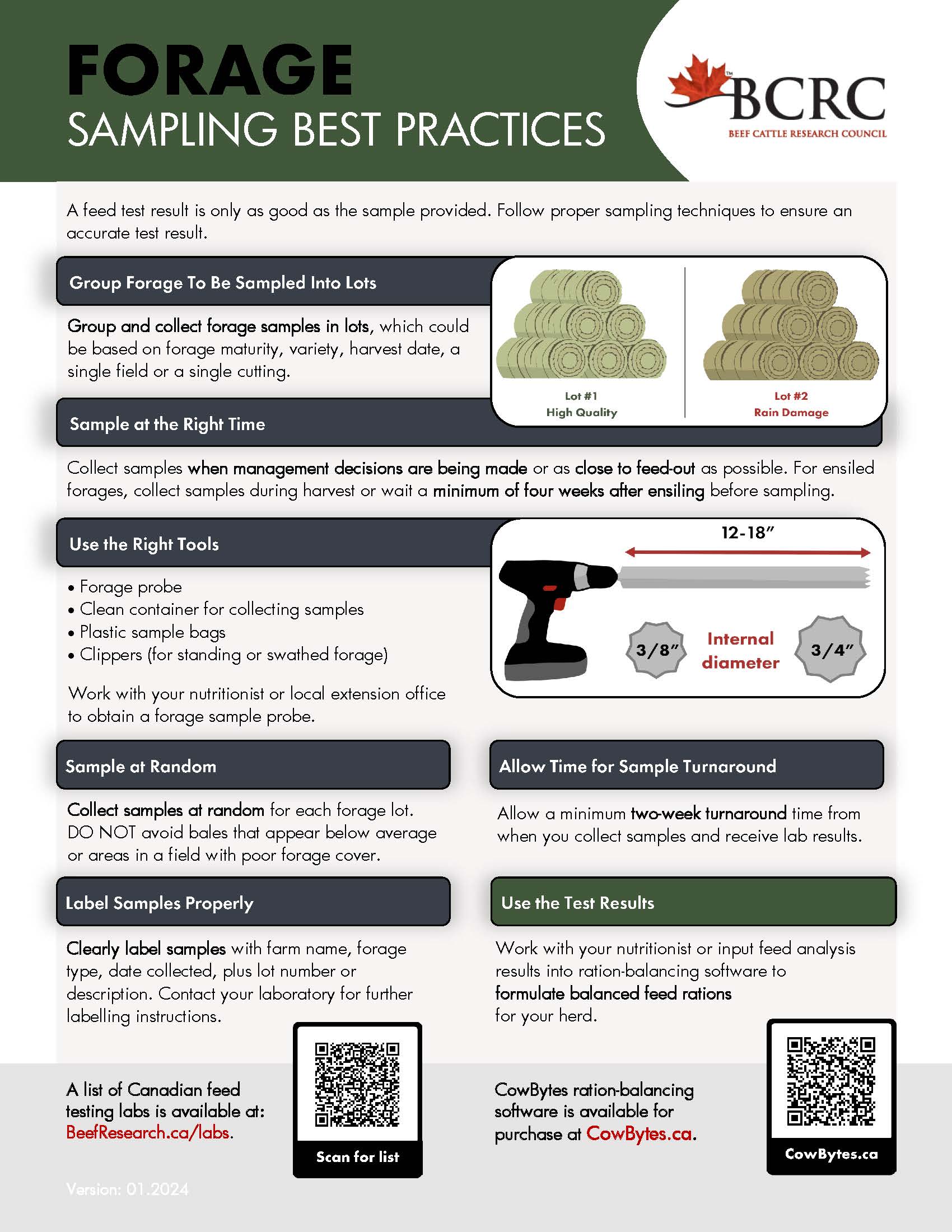

Il est crucial de prélever un échantillon d’aliment représentatif de l’ingrédient ou des ingrédients de l’aliment que vous testez. Tout type d’aliment qui sera utilisé pour nourrir les bovins de boucherie peut et devrait être analysé, y compris les fourrages et la paille en balles,,les sous-produits, l’ensilage, l’ensilage en balles, les céréales, le pâturage en andains et les cultures de couverture.

La qualité des aliments pour animaux évolue au fur et à mesure que la saison d’alimentation progresse. Les échantillons devraient être prélevés aussi près que possible de la période d’alimentation ou de vente, tout en laissant suffisamment de temps pour que les résultats reviennent du laboratoire. Il est recommandé de procéder régulièrement à de nouveaux échantillonnages afin de garantir que les résultats sont aussi précis que possible tout au long de la saison d’engraissement. Si les résultats des échantillons et les modèles d’équilibrage des rations ne correspondent pas, il peut être nécessaire de mettre à jour les échantillons. Il est recommandé de prévoir un délai minimum de deux semaines pour les résultats des échantillons après leur soumission.

L’équipement nécessaire au prélèvement d’échantillons comprend une sonde à fourrage, un seau de mélange et des sacs à échantillons. Certains comtés, municipalités rurales, associations de recherche appliquée et laboratoires de tests de fourrage offrent également la possibilité de louer des sondes. Les sondes à fourrage peuvent être achetées dans les magasins de fournitures agricoles et leur prix varie d’environ 100 dollars à plus de 500 dollars pour les modèles qui fonctionnent à l’aide d’une perceuse.

Vidéo : Test d’aliments – Considérations sur la façon de le faire ?offert en anglais seulement

Pour tous les échantillons, étiquetez clairement les sacs d’échantillons en indiquant votre nom, le type d’aliment, le lot/la zone où l’échantillon a été prélevé, la date et toute remarque susceptible d’influencer les résultats.

Vous trouverez ci-dessous des recommandations de meilleures pratiques pour la collecte d’échantillons de différentes sources d’aliments pour animaux:

Cliquez pour voir un PDF sur les échantillons d’aliments pour animaux

FOURRAGES SECS ET EN BALLES

Avant de prélever des échantillons, il est recommandé de séparer les stocks de fourrage en groupes présentant des caractéristiques similaires – par exemple, le même champ, la même maturité au moment de la coupe et la même composition végétale. Cela permettra aux producteurs d’allouer les aliments de manière appropriée en fonction de la qualité et des besoins des bovins de boucherie.

Il est recommandé de prélever des échantillons à l’aide d’une sonde à fourrage, car les échantillons pris avec la main ne seront pas suffisamment représentatifs pour donner des résultats précis.

Recommandations pour l’échantillonnage des fourrages secs et en balles:

Où envoyer les échantillons ?

Les échantillons d’aliments pour animaux peuvent être envoyés à des laboratoires à travers le Canada et les États-Unis. Une liste des laboratoires canadiens est disponible ICI. Les laboratoires devraient être choisis en fonction de la pertinence des mesures (NIR ou chimie humide) pour les nutriments qui vous intéressent et être prêts à fournir des détails sur la manière dont chaque test/calcul est effectué. Les forfaits de tests standards des laboratoires commerciaux coûtent entre 18 et 200 $ selon la série de tests effectués, mais peuvent atteindre 450 à 500 $ pour les analyses spécialisées.Recommandations d’échantillonnage pour le fourrage sec haché

ENSILAGE

Les mêmes principes généraux de collecte d’échantillons de fourrage sec s’appliquent à la collecte d’échantillons d’ensilage. Il existe différentes recommandations pour l’échantillonnage de l’ensilage en fonction du type de système de stockage utilisé. Si la fosse ou le silo-couloir d’ensilage est ouvert, il est possible de prélever des échantillons en surface avec la main. Si un silo-couloir ou un sac n’a pas encore été ouvert, une sonde à fourrage peut être utilisée pour prélever des échantillons sur le dessus ou les côtés. N’oubliez pas de refermer les zones qui ont été ouvertes pour prélever un échantillon afin d’éviter toute détérioration.

Il est important d’attendre au moins 4 semaines après l’ensilage avant de prélever un échantillon. Ce délai devrait permettre au processus de fermentation de se stabiliser.

Recommandations pour l’échantillonnage d’ensilage stocké dans un silo-couloir:

Recommandations pour l’échantillonnage d’ensilage stocké en sac:

Recommandations pour l’échantillonnage d’ensilage stocké dans un silo vertical:

Recommandations pour l’échantillonnage d’ensilage frais :

Cliquez pour afficher les exemples de flux PDF

Il est important de conserver immédiatement les échantillons d’ensilage dans un congélateur ou un autre endroit frais afin d’éviter leur détérioration. Dans l’idéal, les échantillons devraient être conservés à l’état congelé et expédiés en une journée avec un bloc de glace. Toutefois, si l’ensilage a un taux d’humidité idéal et qu’il est bien scellé, avec une évacuation maximale de l’oxygène du sac, il devrait pouvoir être conservé jusqu’à deux jours. Il est également préférable d’envoyer l’échantillon en début de semaine afin d’éviter tout délai durant la fin de semaine, au cours de laquelle l’échantillon demeure dans un entrepôt.

ENSILAGE EN BALLES (OU ENSILAGE PRÉFANÉ)

L’ensilage en balles, également connu sous le nom d’ensilage préfané, est obtenu en mettant en balles du fourrage très humide à l’aide d’une presse à fourrage ronde classique ou d’une presse à fourrage carrée de taille moyenne et en enfermant les balles dans du plastique afin d’exclure l’oxygène et de permettre la fermentation.

Recommandations pour l’échantillonnage d’ensilage en balles:

PÂTURAGE EN ANDAINS ET CULTURE SUR PIED

Pour les cultures sur pied destinées au pâturage ou au pâturage en andains, les producteurs peuvent prélever des échantillons de coupes dans le champ. Il est important de couper les tiges à une hauteur que les bovins sont susceptibles de manger. Il est généralement recommandé de laisser les 4 premiers centimètres de la tige. Veillez à ce que les échantillons soient prélevés dans des zones représentatives du champ, en tenant compte des points hauts, des points bas, des points humides ou des lignes de clôture.

Recommandations pour l’échantillonnage de cultures sur pied et d’andains:

CÉRÉALES, GRANULÉS, SOUS-PRODUITS ET ALIMENTS DE SUBSTITUTION

Les céréales et les aliments pour animaux faits à partir de sous-produits qui seront donnés aux bovins de boucherie devraient être testés avant ou à la réception. Il est recommandé de prélever l’échantillon pendant le déchargement, lorsque cela est possible.

La composition nutritionnelle de certains sous-produits peut être extrêmement variable d’un chargement à l’autre ou d’un fournisseur à l’autre. Dans certains cas, la teneur en humidité varie également pour certains aliments faits à partir de sous-produits. En raison de ces variations, il est recommandé de prélever un échantillon de chaque chargement reçu et de l’envoyer pour analyse.

Recommandations pour l’échantillonnage de grains, de granulés et de sous-produits lors du déchargement:

Recommandations pour l’échantillonnage de grains, de granulés et de sous-produits dans une cellule:

Pour quels éléments devrais-je effectuer des tests ?

Cela peut dépendre des types d’aliments testés, des décisions de gestion que vous devez prendre et du montant que vous êtes prêt à dépenser. En règle générale, les analyses du foin et des fourrages verts doivent porter sur la matière sèche, les protéines brutes, les fibres détergentes acides et neutres, le calcium, le phosphore, le potassium et le magnésium. Les analyses de l’ensilage doivent également inclure le pH ; si le pH est inférieur à 5, l’ensilage a été correctement fermenté.

Le fourrage mis en balle ou ensilé lorsqu’il est trop humide peut subir un échauffement et prendre une couleur brune à noire avec une odeur douceâtre semblable à celle du tabac. Cela signifie qu’une partie des protéines du fourrage ne sera plus disponible pour l’animal. Si l’on soupçonne des dommages par échauffement, il convient de demander une analyse de l’azote ou des protéines insolubles au détergent acide (AIDA ou PIDA). L’échauffement peut également produire des nitrites, qui sont dix fois plus toxiques que les nitrates.

Certains aliments pour animaux faits à partir de sous-produits (tels que les drêches de distillerie) ou les fourrages annuels (tels que le colza ou la moutarde) peuvent présenter des teneurs élevées en sulfates. Cela peut provoquer la polio chez les bovins. Les nitrates et les mycotoxinessont également à prendre en considération.

Spectroscopie de réflectance dans le proche infrarouge (NIRS)

Il est important de comprendre les avantages et les limites des méthodes de test. La NIRS utilise différentes longueurs d’onde de la lumière pour interpréter le type et la quantité de nutriments organiques présents dans un échantillon. Les valeurs d’étalonnage de la NIRS sont basées sur la chimie humide (l’étalon de référence pour l’analyse des fourrages), mais il est important de s’assurer que le laboratoire utilise des équations NIRS adaptées aux échantillons testés. Par exemple, une équation d’étalonnage différente doit être utilisée pour la paille de colza par rapport au foin de graminées mixtes et pour les types d’échantillons frais ou séchés. Les étalonnages des minéraux sont basés sur une relation indirecte entre les minéraux et les molécules organiques présentes dans l’échantillon, ne tenant pas compte des sources inorganiques, ce qui peut conduire à des taux d’erreur plus élevés lorsque la NIRS est utilisée pour les analyses minérales. La NIRS est généralement plus rapide et moins coûteuse que la chimie humide, mais cette dernière peut donner des résultats plus précis pour certaines analyses (en particulier les minéraux).

Comment interpréter les résultats

Un outil pour évaluer les résultats des tests sur les aliments pour animaux

Cet outil évalue la capacité d’un aliment particulier à répondre aux besoins nutritionnels de base de différentes catégories de bovins à différents stades de production dans des circonstances normales. Il n’est pas conçu pour être utilisé dans l’équilibrage des rations, mais plutôt pour vous alerter sur les problèmes potentiels liés aux ingrédients individuels des aliments. Ces résultats ne s’appliquent pas si les vaches sont en mauvaise condition, si le temps est extrêmement froid, humide ou venteux, et ne tiennent pas compte de la dépense énergétique supplémentaire associée au pâturage en andains. Il est fortement recommandé à l’utilisateur de demander conseil à un professionnel qualifié ou d’utiliser le logiciel d’équilibrage des rations CowBytes pour développer une ration équilibrée pour toutes les classes de bovins ou pour évaluer les ingrédients lors de la semi-finition des veaux et du développement des génisses.

Étape 1 Les options sous Sélectionner la classe de bovins sont : génisses de premier veau, vaches adultes et taureaux adultes.

Étape 2: Sélectionner l’étape de production (pour les génisses de premier veau, les vaches adultes ou les taureaux adultes).

Étape 3: Saisissez le poids du bovin en livres dans la cellule BLEUE de la rangée 20 – les tranches acceptables sont de 850 à 1400 livres pour les génisses de premier veau, de 1100 à 1600 livres pour les vaches adultes et de 1800 à 2500 livres pour les taureaux adultes ; les tranches intermédiaires seront arrondies à l’unité inférieure, p. ex.

Étape 4: Saisir les résultats de vos propres tests sur les aliments sur la base de la matière sèche, en commençant par la matière sèche (MS, %). Cliquer sur Calculer les données d’un aliment particulier pour obtenir vos résultats.

Interprétation:

Les réponses indiquent que l’aliment est approprié et sont codées par couleur. Le vert indique que le nutriment est adéquat pour répondre aux besoins nutritionnels. Le jaune se situe à +/- 2,5 % des besoins en TND, à +/- 5 % des besoins en PB et à 0,05 % des besoins en minéraux. Le rouge indique que l’aliment ne répond pas aux besoins des animaux.

Les couleurs des indicateurs sont liées aux besoins nutritionnels d’un type d’animal et d’un stade de production spécifiques. Si le type d’animal ou le stade de production est modifié, les couleurs indiquant l’aptitude à l’utilisation peuvent changer. Par exemple, les besoins nutritionnels d’une vache en fin de gestation sont nettement plus élevés que ceux d’une vache en début de gestation. Un aliment qui n’est pas adéquat pour un groupe peut être satisfaisant pour un autre type d’animal.

* Les calculs sont basés sur des “règles empiriques” nutritionnelles généralement acceptées, dérivées de CowBytes, des besoins en nutriments des bovins de boucherie du Conseil national de la recherche et du ministère de l’Agriculture et des Forêts de l’Alberta.

CLIQUEZ ICI POUR TÉLÉCHARGER LA VERSION EXCEL DE CE CALCULATEUR

La qualité des aliments pour animaux varie en fonction de l’espèce fourragère, du stade de maturité au moment de la récolte, de l’altération des fourrages, des conditions de stockage, des maladies des plantes et d’autres facteurs. Il est important de ne pas se fier aux moyennes et de tester les aliments chaque année. La qualité des fourrages peut varier considérablement au sein d’un même champ et d’une année à l’autre.

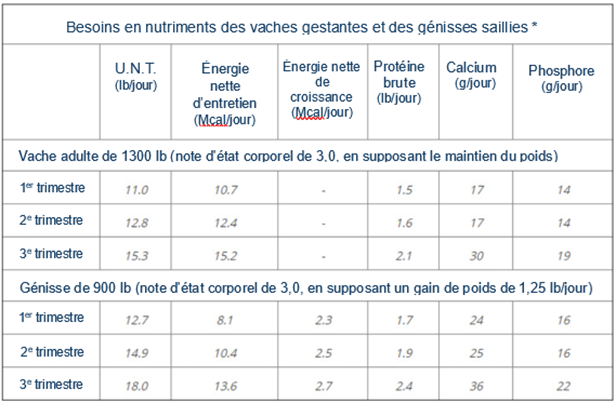

Répondre aux besoins en nutriments des bovins

La principale raison pour laquelle les producteurs devraient tester leurs aliments est de s’assurer qu’ils répondent aux besoins nutritifs de leurs bovins. Les besoins nutritionnels nutritionnels varient considérablement en fonction du stade et de l’âge des bovins et dépendamment de si vous êtes en phase d’élevage, de finition, de reproduction ou d’entretien des bovins. Lanote d’état corporel, l’épaisseur de la peau et le pelage peuvent affecter les besoins nutritionnels des bovins, tout comme les conditions météorologiques telles que les précipitations, la température et la vitesse du vent, ou les facteurs environnementaux tels que la profondeur de la boue, l’espace au distributeur de fourrage, ou d’autres facteurs. Le tableau suivant donne un exemple des besoins en nutriments des vaches par rapport à ceux des génisses pleines. Une règle empirique commune est 55-60-65 et 7-9-11 pour les pourcentages d’U.N.T. et de PB, respectivement, requis par une vache de boucherie au début, au milieu et à la fin de la gestation.

* Les valeurs proviennent de www.BeefResearch.ca et ont été générées à l’aide du logiciel d’équilibrage des rations CowBytes, avec des suppositions incluant la reproduction pour un vêlage le 1er juin, des hivers canadiens typiques, l’accès à un abri contre le vent et un gain quotidien de 1,25 livres pour les génisses pleines, en plus du gain de poids de la gestation.

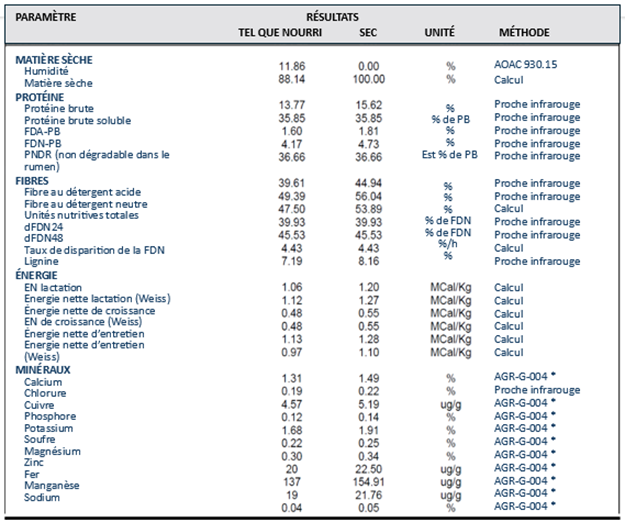

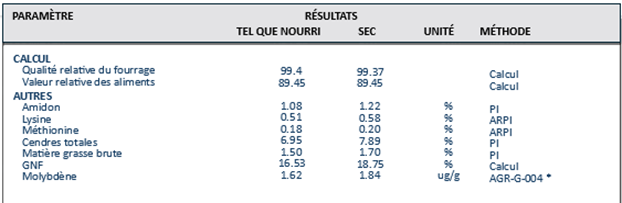

Interprétation des résultats de laboratoire

La plupart des laboratoires fournissent des informations de base sur la teneur en eau, les protéines, l’énergie, le total des nutriments digestibles, les fibres et certaines vitamines et minéraux. Des tests plus spécialisés peuvent inclure des résultats concernant le pH, l’AIDA, les nitrates, les toxines, la valeur alimentaire relative (VAR) et d’autres paramètres. Voici un exemple de résultats d’analyse d’un foin de mélange de graminées et de luzerne :

Exemple de résultats de laboratoire pour un foin sec de mélange graminées-luzerne.

Lamatière sèche (MS, %) correspond à la teneur en eau de l’échantillon d’aliment. La teneur en eau du fourrage dilue les nutriments. Il est donc important d’équilibrer toutes les rations sur la base de la matière sèche. La ration journalière d’un bovin adulte est de 1,75 % à 2,5 % du poids corporel sur la base de la matière sèche. Des teneurs en humidité en dehors des fourchettes prévues peuvent indiquer des problèmes d’altération potentiels. La matière sèche moyenne du foin est de 85 à 90 %, ce qui signifie que le foin contient en moyenne 10 à 15 % d’eau. Pour l’ensilage, la matière sèche moyenne est de 30 à 45 %, ce qui signifie qu’au cours d’une année moyenne, l’ensilage contient 55 à 70 % d’humidité. Cette teneur peut être inférieure si l’ensilage est récolté dans des conditions plus sèches. Les céréales ont une teneur moyenne en matière sèche de 90 %, ce qui signifie que jusqu’à 10 % peuvent être constitués d’eau. L’exemple ci-dessus montre une teneur en matière sèche de 88 %, ce qui correspond à la fourchette idéale pour le foin sec.

Les cendres (%) représentent la composante inorganique (minérale) présente dans les plantes et sont inversement liées à l’énergie. Dans un échantillon de fourrage, les cendres peuvent également provenir de sources externes telles que le sol ou la litière. Une teneur excessive en cendres (>5 % pour l’ensilage de maïs, >8 % pour la luzerne, >6 % pour les graminées et >10 % pour les légumineuses) peut indiquer une contamination externe de l’échantillon. Les résultats ci-dessus montrent une teneur en cendres de 7,89 % pour un foin de mélange graminées-luzerne. Bien que ce niveau ne soit pas excessivement élevé, il indique une possible contamination par le sol.

Les protéines brutes (PB, %) sont une estimation de la teneur totale en protéines d’un aliment, déterminée en analysant la teneur en azote de l’aliment et en multipliant le résultat par 6,25. Les protéines brutes comprennent les protéines réelles et les sources d’azote non protéiques telles que l’ammoniac, les acides aminés et les nitrates. La digestibilité des protéines peut varier et les protéines peuvent être liées à des formes indigestes (protéines endommagées par la chaleur).

Fibre au détergent neutre (FDN %), est une mesure de la teneur en fibres insolubles de la plante, qui comprend les composants de la paroi cellulaire de la plante.

“Des teneurs élevées en FDN (supérieures à 70 %) entraînent une digestibilité plus faible et une réduction des apports volontaires.”

Les fourrages plus matures ont des teneurs en FDN plus élevées. Dans l’exemple ci-dessus, une teneur en FDN de 56 % est suffisante.

Fibre au détergent acide (FDA, %) mesure les parties les moins digestibles de la plante (c’est-à-dire la cellulose et la lignine) et présente une corrélation négative avec la digestibilité totale. Les légumineuses de haute qualité ont généralement une valeur en FDA comprise entre 20 et 35 %, tandis que les graminées peuvent avoir une valeur comprise entre 30 et 45 %. Dans l’exemple ci-dessus, la valeur en FDA de 44,94 % est élevée pour un fourrage à base de graminées et de luzerne, ce qui signifie qu’il existe un potentiel de réduction de la digestibilité.

L’azote insoluble au détergent acide (AIDA), (% des protéines totales) également appelée protéine insoluble au détergent acide, protéine brute insoluble au détergent acide, protéine fibreuse au détergent acide, protéine insoluble ou protéine liée, est une mesure des dommages causés par la chaleur pendant la récolte et le stockage, qui peuvent lier les protéines et les rendre indisponibles pour les bovins. Un niveau de 3 à 8 % d’AIDA peut être présent dans les aliments pour animaux en l’absence totale de chauffage. L’exemple ci-dessus présente une très faible teneur en PB-FDA de 1,81 %, ce qui indique qu’il n’y a pas de dommages causés par la chaleur.

Unités nutritives totales (U.N.T., %) sont définies comme les glucides digestibles + les protéines digestibles + (matières grasses digestibles x 2,25), ce qui reflète la plus grande densité calorique des matières grasses. La valeur en U.N.T. peut être convertie en estimations de l’énergie digestible, métabolisable ou nette. Elle est plus utile et plus précise pour les rations composées principalement de fourrages à base de plantes.

Énergie nette (EN) est une mesure de l’énergie disponible pour l’animal à des fins d’entretien et de production (croissance, gestation et lactation). Les besoins en EN pour l’entretien, la croissance et la lactation sont désignés respectivement par NEm (énergie nette d’entretien), NEg (énergie nette de croissance) et NEl (énergie nette de lactation).

Glucides non fibreux (GNF) représentent les composants solubles de la plante stockés dans la paroi cellulaire (amidon, sucre, fibres solubles, acides organiques) et fournissent de l’énergie à l’animal. La population microbienne présente dans le rumen décompose les GNF pour les utiliser comme source d’énergie. Les niveaux de GNF seront plus faibles lorsque les portions de FDA et de FDN sont plus élevées. Le foin de luzerne a une teneur moyenne en GNF d’environ 30 %, tandis que le foin de graminées a une teneur d’environ 19 %. L’échantillon ci-dessus a une valeur en GNF de 18,75 %, ce qui est proche de la moyenne pour le foin de graminées et indique un fourrage de bonne qualité.

Valeur alimentaire relative (VAR) est un indice qui évalue l’ingestion et la digestibilité et qui est utile pour évaluer uniquement le foin ou l’ensilage de luzerne à 100 %, le foin de luzerne à pleine floraison étant utilisé comme référence avec une VFR de 100. Les valeurs inférieures à 80 ne répondent normalement pas aux besoins énergétiques des animaux. Elle n’est pas fiable pour le foin mixte, le foin de graminées ou le fourrage vert de céréales. Elle est souvent utilisée pour déterminer les prix, mais n’est pas utile pour équilibrer les rations.

Qualité relative du fourrage (QRF) est un indice qui permet d’estimer l’ingestion et les U.N.T. L’estimation de l’ingestion est basée sur des équations différentes pour les graminées par rapport aux légumineuses ou aux mélanges légumineuses-graminées et inclut des facteurs supplémentaires pour améliorer la précision de la prédiction, ainsi que des mesures in vitro de la digestibilité des U.N.T. La QRF peut être utilisée pour les légumineuses, les graminées et les mélanges légumineuses- graminées. La valeur en QRF pour le foin de luzerne en pleine floraison sera similaire à la VAR, mais lorsque les échantillons diffèrent en termes de digestibilité des U.N.T., la QRF sera différente de la VAR.

De nombreux rapports d’analyse d’aliments comprennent des calculs de l’énergie digestible, de l’énergie métabolisable, de l’énergie nette de croissance, de l’énergie nette de lactation et de l’énergie nette d’entretien. Il peut y avoir des différences dans la manière dont ces calculs sont effectués entre les laboratoires. Vous pouvez entrer les résultats de votre fourrage dans le calculateur en haut de la page pour voir s’il convient à l’alimentation des bovins tel quel ou s’il faut le mélanger à d’autres aliments.

Prévenir les problèmes

L’un des principaux avantages de l’analyse des aliments est la prévention de problèmes coûteux et dévastateurs avant qu’ils ne se produisent. Chaque saison est différente et certaines années, il y a une abondance de fourrage de haute qualité. D’autres années, il n’y a pas assez d’aliments disponibles, ou bien il y a une abondance de fourrage, de céréales ou de sous-produits céréaliers de mauvaise qualité qui peuvent sembler économiques, mais qui peuvent présenter des risques importants si une analyse des aliments n’a pas été effectuée ou si elle n’a pas été comprise.

Moisissures et toxines

Les moisissures peuvent apparaître dans les fourrages, les céréales, le trèfle, le maïs et les sous-produits ou dérivés de ces ingrédients alimentaires. Les moisissures sont dues à des maladies des plantes telles que l’ergot, la fusariose, l’aspergillus et bien d’autres. L’incidence de ces maladies végétales augmente lorsque les conditions de croissance sont fraîches et humides, ou dans les cultures laissées sur pied pendant l’hiver. La moisissure réduit la teneur en énergie et le caractère appétissant des aliments pour animaux. Les aliments moisis peuvent également entraîner des problèmes de production, notamment des avortements et des maladies respiratoires, ainsi que le développement de mycotoxines dans les aliments. Les mycotoxines telles que les alcaloïdes de l’ergot, la vomitoxine et l’aflatoxine peuvent entraîner un échec de la reproduction, une réduction de la production laitière, une diminution des gains de croissance, des convulsions, des symptômes de gangrène (c’est-à-dire le dépérissement des sabots, des oreilles ou de la queue) et la mort.

Il n’est pas toujours possible d’éviter les moisissures dans les aliments pour animaux. Il est donc important de tester les aliments pour déterminer la quantité et le type de moisissures présentes afin que les producteurs puissent faire face à la situation de manière réaliste. Évitez de donner des aliments moisis aux jeunes bovins ou aux femelles en gestation et demandez conseil à un nutritionniste sur les façons sûres de mélanger les aliments potentiellement problématiques afin de diluer les contaminants. Prairie Diagnostic Services Inc. a mis en ligne un calculateur de mycotoxines utile pour aider les producteurs à déterminer leur niveau de risque.

Accéder au calculateur en ligne ICI..

Nutrition minérale

La nutrition minérale fournie par les fourrages dépend des éléments suivants:

Les oligo-éléments, en particulier le cuivre, le zinc et le manganèse, sont importants pour la reproduction, la santé et la croissance d’un animal et nécessitent presque toujours une supplémentation. D’autres minéraux, tels que le molybdène et le soufre, ont des propriétés antagonistes qui empêchent l’animal de les absorber. Les réserves en eau qui contiennent des niveaux élevés de sulfates ou les fourrages qui contiennent des niveaux élevés de soufre, tels que les Brassicas (canola, radis, navet), peuvent interférer avec l’absorption du cuivre et provoquer des carences. Les sols et/ou les fourrages riches en molybdène peuvent également entraîner des carences en cuivre, de sorte que les producteurs doivent tenir compte de toutes les sources de minéraux lorsqu’ils se concertent sur leurs besoins en matière de supplémentation.

Dans la plupart des cas, il est recommandé de donner des suppléments de minéraux tout au long de l’année. Les producteurs devraient travailler avec un nutritionniste pour s’assurer qu’ils comprennent le fonctionnement de leur programme de supplémentation en minéraux et qu’ils répondent aux besoins de leur bétail en fonction du stade de la reproduction ou de la gestation. Il est également essentiel de déterminer si les produits qu’ils achètent sont consommés (et si les minéraux sont absorbés) à des niveaux appropriés, par tous les bovins.

Nitrates

Les cultures annuelles telles que l’avoine, l’orge, le maïs ou le millet peuvent accumuler des nitrates dans certaines conditions de croissance, notamment en cas de sécheresse sévère, de tempête de grêle ou de gel. Les bovins peuvent métaboliser un certain niveau de nitrates, mais si le régime alimentaire contient plus d’environ 0,5 % de nitrates (NO3) sur la base de la MS, une toxicité subclinique peut se produire, entraînant une réduction du gain de poids, une diminution de l’ingestion d’aliments et de la production de lait, ainsi qu’un risque accru d’infections. Les régimes contenant plus de 1 % de NO3 peuvent entraîner la mort et l’avortement. Les vaches adultes et les génisses de premier veau sont les plus exposées et peuvent présenter des symptômes tels que des avortements, des veaux prématurés, la mortalité des veaux nouveau-nés, une faible croissance et une production laitière réduite.

Un test d’alimentation simple et peu coûteux permet d’écarter les problèmes potentiels liés aux nitrates. Selon le niveau de toxicité, l’aliment peut être mélangé pour diluer les nitrates à des niveaux sûrs.

Qu’en est-il de l’eau ?

L’analyse des aliments est essentielle, mais les bovins de boucherie tirent également des nutriments de l’eau. Les producteurs doivent envisager d’échantillonner régulièrement la réserve d’eau afin de prévenir les problèmes nutritionnels. Dans de nombreux cas, le fourrage seul ou l’eau seule peuvent ne pas causer de toxicité chez les bovins, mais lorsque les deux sont combinés, les effets cumulatifs peuvent entraîner des problèmes. Cela peut être particulièrement vrai pour les sulfates ou les nitrates et peut se produire dans des situations de pâturage ou d’alimentation hivernale.

L’analyse de la qualité de la réserve d’eau peut s’avérer particulièrement importante en cas de sécheresse, lorsque les minéraux et les nutriments peuvent se concentrer en raison de la baisse des nappes phréatiques dans les eaux de surface ou souterraines, ou de l’évaporation dans les étangs de réserve.

Pour plus d’informations sur l’analyse de l’eau, la qualité et les systèmes, consultez le site suivant: /topics/water-systems-for-beef-cattle

Formulation des rations

Lorsque les résultats des analyses d’aliments sont disponibles, les producteurs peuvent formuler une ration appropriée pour leurs bovins en faisant appel aux services d’un nutritionniste qualifié, à l’assistance du personnel de vulgarisation agricole ou à un logiciel tel que CowBytes (version 5). CowBytes est actuellement disponible à l’achat auprès du BCRC. Il existe également plusieurs tutoriels en ligne gratuits et utiles.

Des rations différentes doivent être développées pour autant de classes de bovins distinctes que nécessaire. Les producteurs peuvent choisir de regrouper leur troupeau en fonction de leurs besoins. Par exemple, un troupeau reproducteur peut être divisé en un groupe de vaches adultes qui ont une bonne note d’état corporel et ont simplement besoin d’être entretenues, et un autre groupe de vaches plus âgées ou maigres qui ont besoin de prendre du poids.

Les minéraux et le sel doivent le plus souvent être ajoutés au cours de la période d’alimentation hivernale, en fonction des résultats des tests sur les aliments. Pour les rations composées principalement de luzerne, d’herbe ou d’un mélange des deux, le calcium et le phosphore doivent généralement être supplémentés dans une proportion de 1:1. Pour les rations qui contiennent davantage de fourrages à base de céréales, y compris des granulés, de la paille ou du fourrage vert, il peut être nécessaire d’ajouter un mélange de 2:1 ou 3:1. Les besoins des animaux évoluent également au cours de la gestation et de la lactation.

Intéressé par l’analyse des aliments pour animaux ? Quelle est la prochaine étape ?

Un outil d’évaluation de la valeur économique des aliments pour animaux basé sur la teneur en éléments nutritifs

Cet outil vous aidera à déterminer la valeur des aliments que vous envisagez d’acheter par rapport à la valeur de deux aliments de référence (l’orge et le tourteau de canola sont les exemples actuels, mais ils peuvent être modifiés) en utilisant les prix actuels du marché.

Étape 1: Entrez le prix actuel des aliments pour animaux ($/tonne, tel que servi) pour les aliments de référence (par exemple, grain d’orge, tourteau de canola) dans les cellules correspondantes.

Étape 2: Pour chaque aliment que vous envisagez, saisissez les informations requises dans le tableau des aliments ciblés.

Étape 3: Demandez à un nutritionniste d’établir une ration appropriée pour s’assurer que tous les besoins nutritionnels sont satisfaits.

Étape 4: Déterminez votre meilleure stratégie d’alimentation.

Comment savoir si l’aliment que vous envisagez d’acheter est la meilleure solution pour vous ?

Lorsque vous cherchez à acheter des aliments pour animaux et que vous avez plusieurs sources à considérer, la meilleure solution est de pouvoir calculer la valeur nutritive de chaque aliment par rapport à une source de référence. Un outil simple a été mis au point pour vous aider à le faire.

Fonctionnement de l’outil:

L’ESSENTIEL :

ALIMENTS DE RÉFÉRENCE

L’outil utilise le grain d’orge et le tourteau de canola comme aliments de référence initiaux. Cependant, vous pouvez les remplacer par les aliments de référence qui conviennent le mieux à vos besoins. Le coût actuel rendu à la ferme (c’est-à-dire le coût livré dans la cour) ainsi que la teneur respective en nutriments de ces aliments servent de base pour calculer la valeur nutritive des aliments envisagés pour l’achat.

ALIMENTS CIBLÉS

Les informations relatives aux différents aliments ciblés (prix, pourcentage de matière sèche (MS), unités nutritives totales (U.N.T.) et protéines brutes (PB) sur la base de la matière sèche doivent être saisies dans les cellules vertes du tableau « Aliments ciblés ». Pour une utilisation optimale de ce calculateur, utilisez les données des tests d’alimentation et les prix en vigueur dans votre région.

RÉSULTATS

Les résultats sont calculés dans les trois dernières colonnes du tableau d’aliments ciblés.

La valeur nutritive calculée ($/tonne) est la valeur « économique » estimée de l’aliment pour animaux. Elle est basée sur sa teneur en nutriments (à partir des valeurs de l’échantillon) et sur les valeurs des nutriments calculées à partir des aliments de référence. Plus la valeur est élevée, plus la teneur cumulée en U.N.T. et PB de l’aliment ciblé est importante, plus la valeur de l’aliment est élevée.

La deuxième partie fournit une valeur numérique. Même si elle est exprimée en $/tonne, elle ne peut pas être directement traduite en coût d’alimentation car il ne s’agit pas d’une ration et d’autres composants devront être inclus pour garantir une ration équilibrée. Les chiffres peuvent être utilisés pour déterminer quel aliment a le meilleur potentiel pour être utilisé dans la formulation finale d’une ration. Il s’agit d’un classement simple des aliments (sur la base d’informations limitées sur les nutriments), où la valeur la plus élevée représente la meilleure option à envisager du point de vue du coût. Si toutes les valeurs sont négatives, cela ne signifie pas que vous ne devriez pas envisager d’acheter ces aliments. Cela signifie que l’aliment ayant la valeur négative la plus faible peut être la meilleure option économique à prendre en compte lors de l’élaboration d’une ration et que l’utilisation de cet aliment entraînera probablement la plus faible augmentation du coût global de l’alimentation.

AUTRES CONSEILS POUR UTILISER L’OUTIL :

L’outil est configuré avec du grain d’orge et du tourteau de canola comme aliments de référence standard. Si vous utilisez d’autres aliments ou si vous avez des aliments ayant des teneurs en nutriments différentes, vous pouvez modifier les aliments de référence pour qu’ils correspondent à votre situation personnelle. Par conséquent, les informations calculées dans le tableau “Aliments ciblés” reflèteront davantage votre propre situation.

Le tableau est conçu de manière que vous puissiez également modifier les composants U.N.T. et BP, et utiliser différents éléments nutritifs si nécessaire. Par exemple, si les aliments ne sont utilisés que pour répondre aux besoins d’entretien des bovins (c’est-à-dire des vaches en début de gestation sans lactation ou des taureaux adultes), l’utilisation de l’énergie nette d’entretien (ENe) disponible à partir des résultats des tests d’alimentation devrait donner une estimation plus pertinente de la valeur de l’aliment.

CLAUSES DE NON-RESPONSABILITÉ :

L’impact sur le coût des aliments est divisé en deux parties. La première partie est la colonne indiquant “Négatif” or “Positif”. Si le prix demandé est inférieur à la valeur nutritive calculée, un “Positif” apparaîtra dans la première colonne. Si c’est le cas, vous pouvez considérer que cet aliment est une bonne affaire en raison de sa composition en éléments nutritifs.

CLIQUEZ ICI POUR TÉLÉCHARGER LA VERSION EXCEL DE CE CALCULATEUR

Cette page a été développée par l’Alberta Beef Forage and Grazing Centre.

Remerciements particuliers à : Hushton Block (AAC), Barry Yaremcio (AAF), Herman Simons (AAF), Jennifer Schmid (Excel Wizard).

Commentaires

Les commentaires et les questions sur le contenu de cette page sont les bienvenus. Veuillez nous envoyer un courriel à l’adresse suivante: info@beefresearch.ca.

Révision par un expert

Ce contenu a été révisé pour la dernière fois en mars 2024