Remarque : cette page web n’est actuellement disponible qu’en anglais.

Rangeland, or range, is land supporting native or introduced vegetation that can be grazed and is managed as a natural ecosystem1. Rangeland includes grassland, grazeable forestland, shrubland, pastureland and riparian areas.

The benefits of maintaining healthy rangeland for livestock producers include:

- renewable and reliable source of forage production

- more stable forage production during drought

- greater flexibility and efficiency for extending the grazing season (fall or winter)

- reduced populations of noxious and invasive weeds.

In addition to being a valuable and important forage source, rangelands supply many environmental, economic and social benefits. Management decisions affect rangeland health and productivity and an understanding of how plants and the entire system responds to grazing will positively influence all components.

| Key Points |

|---|

| Knowledge of range plant type, season of growth, origin, response to grazing, and forage value are important considerations for proper management\ |

| Invasive plant species can decrease biodiversity and rangeland health, reduce forage productivity, increase management costs for control, compromise economic and aesthetic value of the land, and elevate physical, nutritional and reproductive health concerns within the grazing herd |

| The basic principles of range management include: |

| – balance livestock demand with forage supply |

| – distribute grazing pressure |

| – provide effective rest periods |

| – manage livestock most suited to the forage supply and objectives |

| The best time to graze is when conditions allow for high rates of photosynthesis for regrowth |

| Healthy rangelands: |

| – produce forage for livestock and wildlife |

| – maintain and protect soil from erosion |

| – capture and release water |

| – cycle nutrients and energy |

| – cycle nutrients and energy |

| Cattle, grass and waterways can coexist if access is controlled through management including timing of grazing, frequency, duration, use of fencing, and off-stream watering sites |

Range Plants

Learning to recognize range plants and their role in the ecosystem is key to good range management.

Range plants can be grouped based on various characteristics including plant type, season of growth, origin, response to grazing and forage value2.

Plant Type

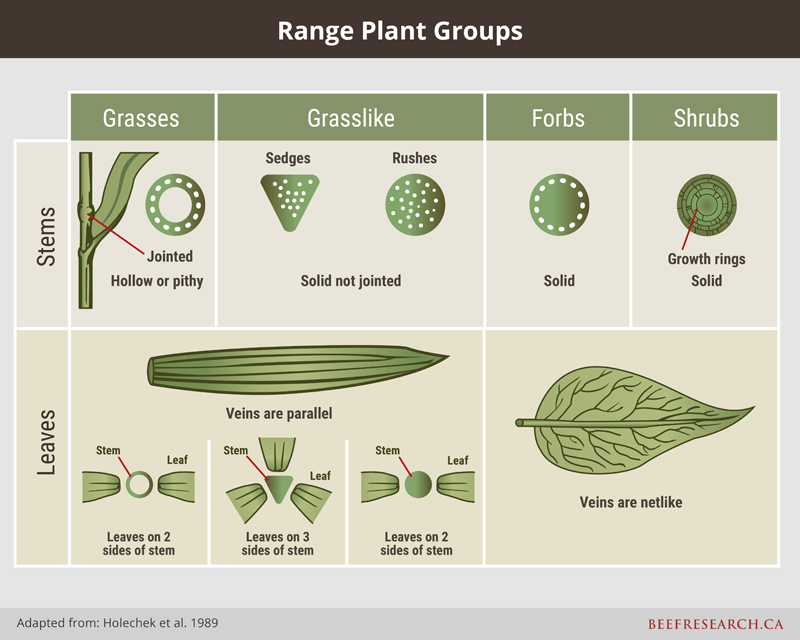

Plant type species groups have similar physical characteristics and include:

- grasses – herbaceous plants with narrow, long, parallel-veined leaves and hollow, jointed stems (e.g. wheatgrasses, bluestems, fescues)

- grass-like plants – similar to grasses but have solid stems (not hollow) that are often three-sided and not jointed. Leaves are no different from grasses. (e.g. sedges, rushes)

- forbs – herbaceous, broad-leaved plants with annual tops and leaves with net-like veins. Includes many kinds of range weeds and flowers (e.g., vetches, yarrow, club moss)

- shrubs – woody, often deciduous perennials with stems that live over winter and branch out from the base or at ground level (e.g., sagebrush, winterfat, snowberry)

Season of Growth

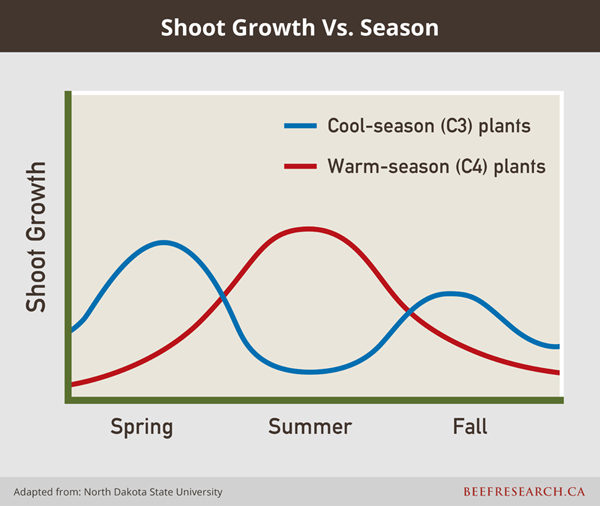

Range plants are also classified and managed according to their season of growth. Cool-season (C3) plants (e.g., wheatgrasses, needlegrass, bromegrass) begin growth in early spring, grow rapidly during early summer and usually become dormant during mid to late summer due to hotter and drier conditions. Most annual growth is produced prior to mid-July. Some cool-season species will resume growth in the fall when temperatures drop and if moisture becomes available.

Warm-season (C4) plants (e.g., blue grama, buffalograss, bluestems) begin growth in late spring continuing through the summer with the majority of annual growth produced from July to mid-September. These grasses use soil moisture more efficiently than cool-season species and withstand drought conditions better3.

Because warm-season grasses have different leaf cellular structures that cause them to be more fibrous, contain more lignin and be less digestible, livestock tend to prefer cool-season grasses over warm-season species at the same growth stage. However, due to the timing of growth of each type, cool-season species are often more mature and entering reproductive stages at the same time that many warm-season grasses begin growth. Therefore, later in the season livestock will typically seek out new growth from warm-season species if available.

Although cool-season species are dominant on many range sites in Canada due to our climate, warm-season species do make up a high percentage of plant cover in some areas (i.e., on sandy or sandy loam soils). Plant communities comprised of a mixture of cool and warm-season species provide biodiversity, forage resources throughout the grazing season, and excellent wildlife habitat.

Plant Origin

Both native and introduced plants can be found on rangelands. Most range plants are native while introduced plants have been brought in from outside North America and were not present in the original plant community. In all cases, management needs to be based on knowledge of growth patterns, history of use, and grazing response.

Response to Grazing

A plant’s response to grazing is affected by soil type, moisture levels and climate. In one environment a plant may react very differently than on a second site. Range plants can be grouped as decreasers, increasers and invaders based on how they respond to defoliation (grazing, fire, insect damage or drought).

- Decreasers are reduced in relative amount with continued disturbances such as heavy grazing.

- Increasers will respond favourably for a period of time under continued disturbance.

- Invaders are usually weedy species that establish themselves when more desirable species have died out from heavy use.

Forage Value

While the majority of range plants are nutritious and highly palatable, rangelands may contain toxic or poisonous plants that can cause illness or death in grazing animals. When these plants are present, stocking practices that maintain a healthy forage stand will reduce risk as animals have adequate forage to choose from and are not forced to graze harmful plants they may normally avoid. Rangeland plant communities can change over time and overgrazing can lead to increases in poisonous species. It is critical to know which poisonous species are present and when they are most hazardous.

The publication, Stock-poisoning Plants of Western Canada, provides a comprehensive overview of native and introduced species that frequently cause poisoning to livestock, including descriptions, geographical distribution, toxic principle and conditions of poisoning.

The Canadian Poisonous Plants Information System includes a comprehensive listing and interactive search tool (by name, affected organism, symptoms, distribution) of plants that cause poisoning in livestock (as well as pets and humans).

Invasive Plants

Invasive plant species are undesirable non-native plants that have spread outside of their natural habitat. In a new environment they can out-compete native plants for space, moisture, and nutrients4. On grazed rangelands, invasive plants can decrease biodiversity and rangeland health, reduce forage productivity, increase management costs for control, compromise economic and aesthetic value of the land, and elevate physical, nutritional and reproductive health concerns within the grazing herd. Examples of invasive plant species relevant to grazing management include leafy spurge and downy brome.

How to Combat Invasive Plants

Beneficial management practices (BMPs) can be implemented to combat invasive plant species, including prevention of their introduction, control of their spread, or elimination of their presence. The Saskatchewan Forage Council factsheet, Grazing: BMPs for Invasive Plant Species, provides an excellent overview of BMPs that can be implemented to assist in efforts to manage invasive plant species.

Several comprehensive, region-specific range plant identification guides are available. As an example, Managing Saskatchewan Rangeland includes a detailed overview of range plants including images, response to grazing and forage value for each species. Contact a local forage, grazing or cattle association, extension specialist or agrologist in your area to access resources specific to your region.

Principles of Range Management

The management of rangelands is based on the following basic principles and practices:

- balance livestock demand with forage supply – balancing grazing animal needs with available forage supply is often referred to as ‘proper use’. Determining the amount of forage to graze while leaving adequate carryover is generally set at 40-50% but may be more or less, depending on growing conditions, the type of plants, and stage of growth.

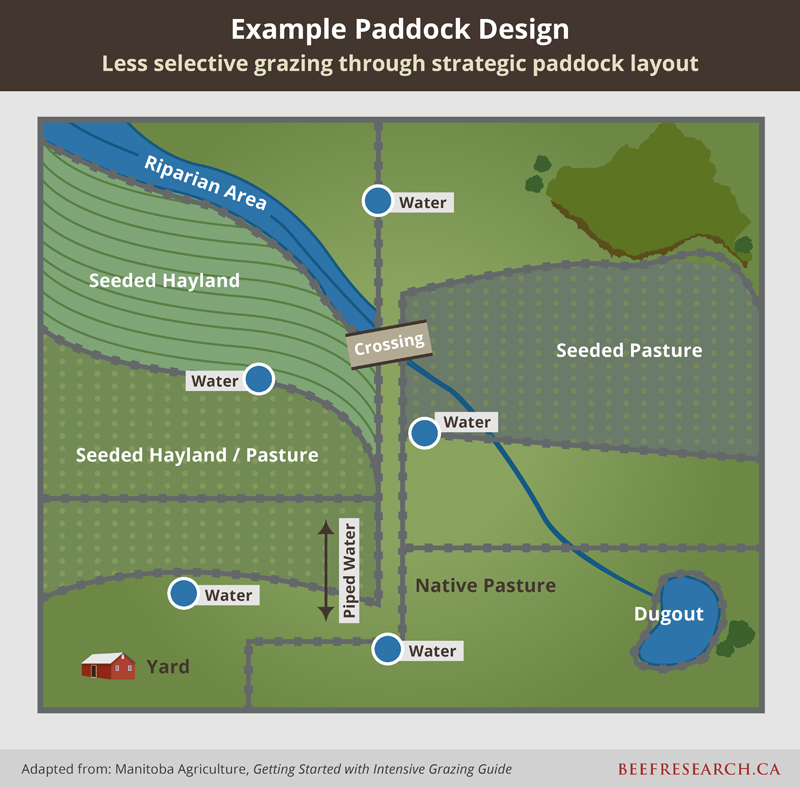

- distribute grazing pressure across the landscape – management of grazing distribution is important to prevent areas of over- or under-utilization. Many factors influence animal grazing patterns (topography, vegetation type, forage palatability, quality and quantity, location of water, salt, mineral, shade and shelter, fences, pasture size, stock density).

- provide effective rest periods after grazing to allow plants to recover – rest is key to prevent overgrazing. The length of time that a plant needs to recover depends on the type of forage, plant vigour, level of utilization, season of grazing, soil type/range site, and environmental conditions.

- manage grazing livestock most suited to the forage supply and management objectives – proper selection and management of grazing animals as a forage-harvesting tool allows range managers to meet the basic principles of range management including balancing demand and supply, livestock distribution, and rest and recovery. Estimating forage requirements for each type and class of livestock includes using animal unit equivalents (AUE) to calculate stocking rates.

Application of these four principles will support healthy productive rangelands. Forage can be grazed to sustain livestock while leaving adequate ungrazed residue (plant litter) behind to sustain rangeland ecosystem function. Strategic fencing, water development and salt placement can help promote more even livestock distribution. Being aware of plant growth patterns will allow for timing of grazing to avoid defoliation when plants are most sensitive to grazing pressure and for implementation of rest periods.

Plant Growth and Recovery After Grazing

Photosynthesis is the basic reaction that plants use to convert solar energy into chemical energy, providing for growth, maintenance, and reproduction. Recovery after grazing depends mainly upon there being adequate green tissue for photosynthesis to occur and produce energy for new growth. Stored plant carbohydrates play a relatively small role in the ability of a plant to recover following grazing. For this reason, removal of too much leaf material will significantly slow recovery.

Plants will recover more quickly following grazing if:

- grazing occurs during active and optimal plant growth periods,

- more leaf area remains after grazing, and

- litter is maintained, which is an indicator of appropriate levels of use.

So, When is the Best Time to Graze?

Grazing during the optimal growth period (which will vary with each forage species) and when growing conditions are favourable, will allow for high rates of photosynthesis and regrowth IF plant material remains after grazing. A general rule of thumb often used as a guideline by grazing managers is a level of utilization of 50%. This generally indicates a moderate level of grazing intensity.

The timing of grazing is less important than making sure that plants are given enough time to rest and recover after grazing. Regrowth takes time and a grazing plan needs to include removing animals from a pasture to ensure that plants are not regrazed before having a chance to recover. Planned grazing systems, such as rotational grazing, employ this knowledge to control grazing animal impacts.

Visit the Grazing Management topic page for a more in-depth overview of grazing principles and practices.

Rangeland Health

“Range health” describes the ability of rangeland to perform certain key functions1. In a healthy rangeland the integrity of the soil, vegetation, water and air, as well as the ecological processes of the rangeland ecosystem, are balanced and sustained5. All parts of the ecosystem are present and working together. Healthy rangelands:

- produce forage for livestock and wildlife

- maintain and protect soil from erosion

- capture and release water

- cycle nutrients and energy, and

- maintain biological diversity.

The original concept of range condition was developed in response to the deterioration of western rangelands caused by grazing mismanagement and included development of published stocking rate guides (Alberta in 19666 and extended to Saskatchewan in 19907). Range condition describes the current state of vegetation compared with that of the potential for the site (known as the climax plant community) and was used to measure either deterioration or improvement. Four classes of range condition (Excellent, Good, Fair, Poor) explain how the composition of the present plant community has changed from that of the climax community.

The range condition approach worked well in semi-arid rangelands and was accepted by land managers; however, a number of shortcomings were identified. One of the key assumptions was that any decline in range condition was reversible and experience showed that that is not always the case. For example, when communities are invaded by non-native species, they may not show a trend back towards to the climax plant community no matter the management treatment applied. Also, the traditional range condition concept does not consider requirements for soil protection or grazing management impacts on soil.

Evaluating range health improves upon the original range condition approach by adding indicators, particularly for soil and site conditions, which producers can observe and are easier to measure than plant community alone. Rangeland health assessment tools have been developed to measure how well management principles and practices are being achieved (see example below). These assessments better address problems like irreversible changes in range condition and invasion of non-native species. Range health determines the ability of rangeland to produce forage, protect the soil, and efficiently cycle water and nutrients in a state of biological diversity.

The following video defines rangelands (0:50), covers the basic principles of range management (1:35), highlights an assessment tool (3:49), and outlines steps in a rangeland assessment (4:33).

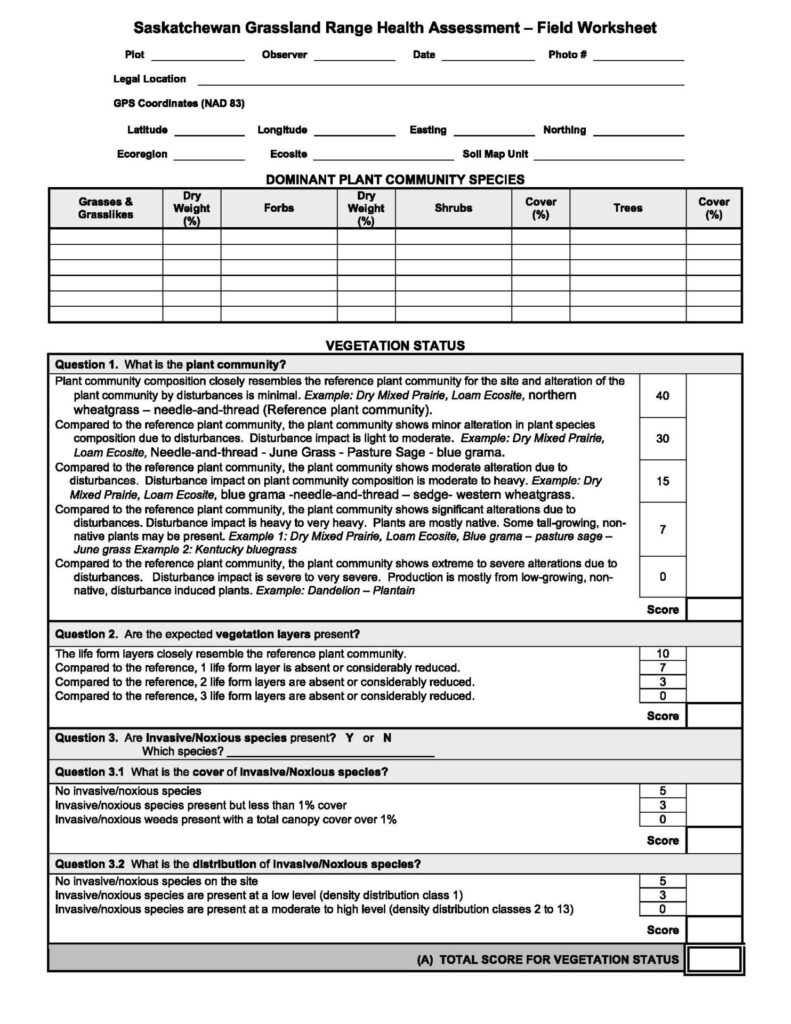

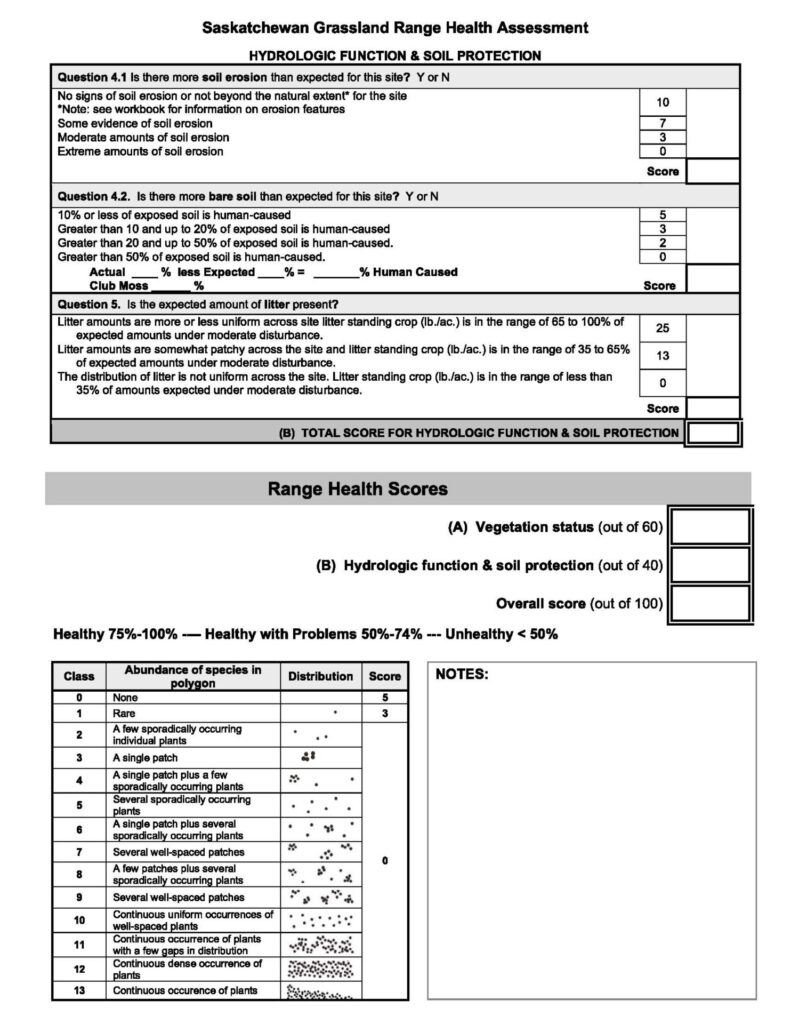

Assessing rangeland health starts by examining the existing plant community for desirability, diversity and density. Grazing severity, soil erosion, litter residue (dead plant material), disturbance and invasive species/noxious weeds are also taken into account in determining range health.

The next video shows a rangeland health assessment conducted on three sites in southern Alberta with varying degrees of grazing pressure. It defines the five key functions of rangelands (1:39) and compares lightly (3:23), heavily (9:55), and very heavily (12:51) grazed pastures.

Range managers use rangeland health assessments to ensure that grazing management practices are not damaging the soil, water or range resource and that management decisions are producing the expected results. Healthy range scores indicate good overall grazing management, but range assessments may still identify specific areas where changes can be made. Declines in range health scores alert managers to consider management changes, especially in those areas that score lower in the assessment.

A two-page sample Grassland Range Health Assessment worksheet1 is shown below illustrating the evaluation of range health indicators and the steps taken to arrive at a range health score (Healthy = 75-100%; Healthy with Problems = 50-74%; Unhealthy < 50%).

Where to Find Assessment Tools?

Rangeland health assessment tools and resources are available in many provinces by contacting regional or provincial forage, grazing or cattle associations, extension specialists, or agrologists.

The Grazing Response Index (GRI) is a simple, short-term monitoring tool to evaluate the effect of the current season’s grazing management. It can be used to make rangeland management decisions for the following year. While the overall GRI value for a pasture can provide direction on where and when to adjust grazing management, it does not monitor rangeland health or measure long-term changes and should not replace vegetation monitoring and assessment.

The Grazing Response Index factsheet, developed by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, provides an overview of the tool, an example ranch assessment, and blank worksheet that can be used to calculate GRI scores for native pastures. The original GRI method has also been adapted for tame forage assessment. The following video, produced by the Saskatchewan Forage Council, provides an excellent overview of the use of the GRI tool.

Over 300 insect species are found in cow dung on Canadian pastures; mating, eating dung, laying eggs, eating each other – all while providing valuable ecosystem services.

The Cow Patty Critters guide is a dung detective’s handbook for studying cow dung communities on pastures across Canada. The second part of the Cow Patty Critters guide provides tools and instructions on how to identify dung insects and other critters.

Riparian Management and Assessment

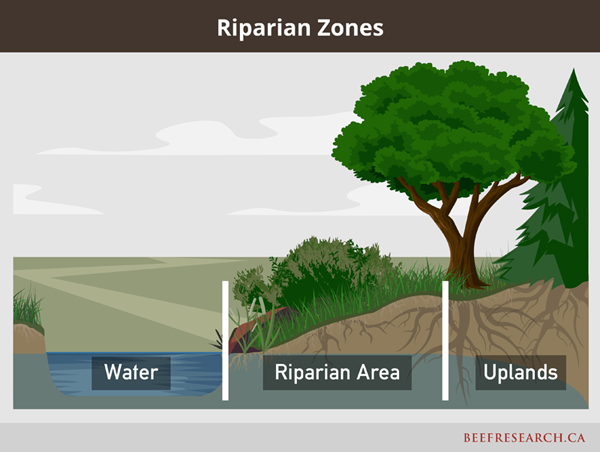

A riparian zone8 is the area adjacent to streams, rivers, lakes, and wetlands, where the vegetation and soils are strongly influenced by the presence of water.

Healthy riparian areas trap and store sediment, build and maintain streambanks, store flood water, recharge groundwater, act as a filter and buffer to maintain water quality, reduce and dissipate stream energy to slow erosion, maintain biodiversity, provide wildlife habitat, and produce forage.

Unhealthy riparian areas are characterized by weeds, reduced forage production, damaged shrub growth, down cutting and erosion of the channel, slumping banks, soil exposure, low water table and decreased storage capacity with few fish or wildlife present.

The following video defines riparian zones (1:01), outlines the benefits of these areas (1:31), and describes assessment of the health of riparian zones (3:01).

Riparian areas are extremely productive components of a grazing program and with proper management cattle, grass and waterways can coexist in a long-term sustainable ecosystem. However, because riparian areas are also important areas for protecting water quality, they are very sensitive to uncontrolled grazing. If access isn’t controlled, cattle will concentrate in a riparian area because of water, salt, shade, or forage availability. Early and mid-summer use can be detrimental to riparian areas unless grazing is limited in duration and frequency so that plants can recover.

Video courtesy of: Southern Alberta Land Trust Society and Cows and Fish

Grazing can work well when grazing duration is managed to minimize browsing, rubbing and trampling of shrubs and small trees. Fall and winter grazing can be successful when forage is sufficient for grazing through the snow, when enough residue is left to slow the water flow from next spring’s runoff, when supplemental feeding sites are far enough away from the riparian area, and cattle are discouraged from resting there. Avoid bale grazing near riparian areas to ensure that nutrient runoff does not flow directly into waterways.

The use of remote or off-stream watering sites can reduce the impacts of livestock in riparian areas with benefits including improved water quality and increased animal performance. In order to attract cattle away from riparian areas to make use of off-stream watering systems, management strategies should consider a grazing plan that ensures adequate forage in upland areas, as well as alternative options for shade and protection from the heat.

The following video outlines strategies, including placement of fences (1:37), to improve and maintain riparian health plus discusses many of the positive outcomes (3:25) that result from good riparian management.

- References

-

1 Prairie Conservation Action Plan. 2008. Rangeland Health Assessment: Native Grassland and Forest. Regina, SK.

2 Alberta Agriculture and Forestry. 2003. Alberta Range Plants and their Classification.

3 Rangelands Partnership. 2019. Range Plants. Global Rangelands, An Initiative of the Rangelands Partnership (U.S. Western Land-Grant Universities and Collaborators). University of Arizona.

4 Saskatchewan Forage Council. 2011. Grazing: BMPs for Invasive Plant Species.

5 Society for Range Management. 1998. Glossary of terms used in range management, Fourth Edition.

6 Johnston, A., S. Smoliak, L.M. Forbes and J.A. Campbell. 1966. Alberta guide to range condition and recommended stocking rates. Alberta Department of Agriculture. Pub. No. 134/14-1. 17pp.

7 Abouguendia, Z.M. 1990. Range Plan Development. New Pasture and Grazing Technologies Project. Regina, SK.

8 Cows and Fish, Alberta Riparian Habitat Management Society.

Feedback

Feedback and questions on the content of this page are welcome. Please e-mail us at info@beefresearch.ca

Expert Review

This content was last reviewed April 2019.

Ce contenu a été révisé pour la dernière fois en Janvier 2024.