Dehorning in Beef Cattle

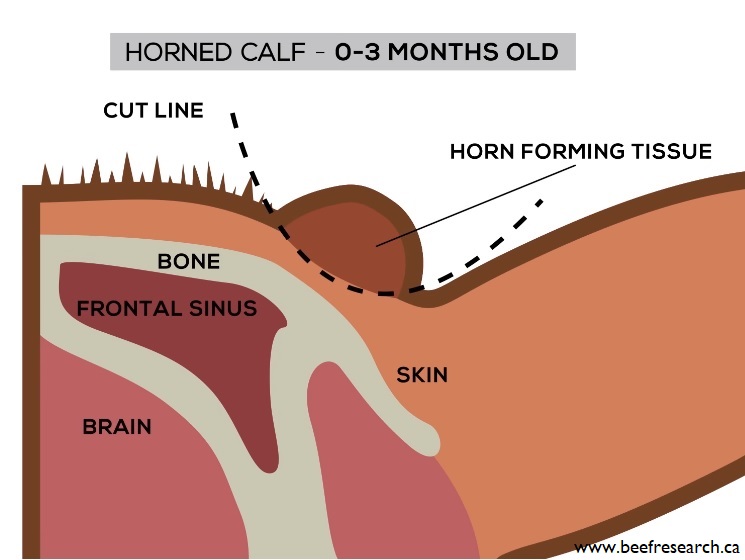

Dehorning beef cattle is a common management practice to reduce the risk of injury and bruising to other cattle and to improve handler safety. Horns are absent at birth but grow from a cluster of cells known as horn buds. Not all cattle have horns and with the availability and adoption of polled genetics, the majority of Canada’s beef herd is polled. Horn buds attach to the skull when a calf is approximately two to three months of age.

Removing horns by disbudding or dehorning is a common management practice in order to:

- Reduce the risk of injury and bruising to other cattle

- Improve farm safety for farmers and animal handlers

- Prevent financial losses due to trimming damaged carcasses

- Minimize space required for feeding and transit

| Key Points |

|---|

| Dehorning must be performed by an experienced person using proper, well-maintained tools and accepted techniques. Dehorning should be performed when the animal is as young as possible, prior to two to three months of age. |

| Producers should consult with their veterinarians regarding pain control when dehorning after horn buds have attached, as indicated in the Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Beef Cattle (2013). |

| Using polled (i.e. hornless) genetics helps reduce the costs, labour, and animal health and welfare issues associated with dehorning. |

| Horn tissue can be physically removed at the bud stage (i.e. disbudding) using caustic pastes or an electric disbudding tool. |

| Physical removal of horns after skull attachment, while not preferred due to pain and other complications, can be done using tools such as a Barnes dehorner, a scoop or tube, a gouger, or dehorning cable. |

| Risks of dehorning include pain, uncontrolled bleeding, fly infestation, and bacterial infection. |

| Pain medication, such as anesthetics and analgesics, is effective at reducing pain and improving welfare. A number of different pain-control products are commercially available and surveys demonstrate producers are using them. |

Carcass Quality Considerations

Recent producer surveys indicate that the majority of herds across Canada are polled. In 2017, 89.3% of western Canadian and 86% of Ontario cow-calf producers reported having >75% polled calves.

According to the latest National Beef Quality Audit, the proportion of all cattle that had horns at slaughter has dropped from 40% in 1994-95 to 9.5% in 2016-17. While the proportion of horned slaughter cattle has dropped, the beef industry still experiences a cost of approximately $0.06/head on all slaughter animals (not just the horned animals) due to additional costs for horn removal at the packing plant. Carcass bruising, partially attributed to horns, caused estimated economic losses of $1.90/head to the beef sector in 2016.

Timing of Dehorning

Calves should be dehorned or disbudded at the youngest age possible, preferably while horn development is still at the horn bud stage (typically 2-3 months). Producers may disbud or dehorn calves at 3-6 weeks or age, at the same time as other common procedures such as castration or vaccination. Dehorning should be avoided during weaning in order to reduce stress.

The Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Beef Cattle requires that dehorning is performed by an experienced person using proper, well-maintained tools and accepted techniques. Producers should consult with their veterinarians regarding pain control when dehorning after horn buds have attached.

Dehorning Methods

Polled genetics

Horns are under genetic control. All cattle carry two copies of the gene, and the gene exists in two versions. The “polled” version of the gene is dominant over the recessive “horned” version. An animal with two copies of the polled version of the gene is “homozygous polled” and will always have polled offspring. An animal with one copy of the polled version and one copy of the recessive horned version is called “heterozygous polled” but will be visibly polled (because the dominant horned version masks the recessive horned version). An animal with two recessive horned versions of the gene will have horns. Breeding horns out of a cattle herd can take several years because some visibly polled cattle may still carry the recessive horned version of the gene.

Breeding for polled cattle is a non-invasive way to dehorn cattle. Polled genetics eliminate the costs, labour, animal health and welfare issues associated with dehorning. Canadian research compared horned and polled bulls and found that there was no difference in birth, weaning or yearling weight, pre- or post-weaning growth rate, scrotal circumference, carcass weight, marbling score, ribeye area or lean meat yield.

Disbudding

Removing the horn buds before they become attached to the skull at two or three months of age is called disbudding. This causes less injury and pain than removing attached horns. Once the cells are permanently destroyed, horn tissue will not be able to grow later in life.

Chemical disbudding involves applying a caustic material, such as a hydroxide-based paste, to the horn buds to kill the horn-producing cells. Discomfort may occur, and care must be taken to ensure the chemical does not come in contact with the calf’s or operator’s skin or eyes. Calves that have had dehorning paste applied should be kept dry and away from other animals, including the mother cow, for approximately six hours post-application.

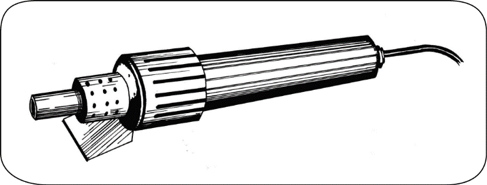

Hot iron disbudding physically burns the horn-producing cells with a special tool. This causes no risk of chemical burns to the skin, eyes or udder.

Figure 1. Electric hot iron disbudding tool

Dehorning

Attachment of horns occurs between two to three months of age. Removing attached horns causes more pain, greater injury, longer recovery time, potential risk of infection, and a greater setback in animal growth.

Some methods are designed for animals that are still young, with small horns.

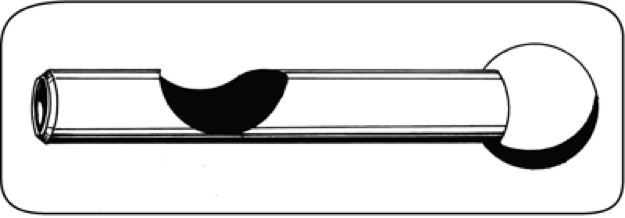

Spoon or tube dehorning uses a special tool designed to cut out the horn bud, along with any horn-producing cells in young animals.

Figure 2. A dehorning spoon or tube

Knivescan also be used to cut around the skin and under the attached horn bud.

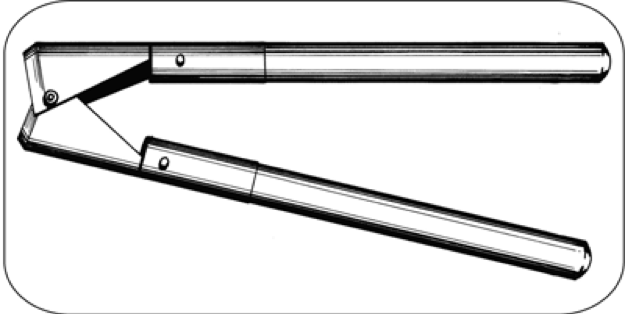

Scoops or gouges are sharpened hinged tubes that slide over the horn and cut the horn along with the horn-producing cells. In older cattle a portion of the skull may also be cut out.

Figure 3. A Barnes-type tool scoops the horn and surrounding horn-producing tissue

Dehorning larger animals is discouraged because of the increase in the size of the wound, the degree of injury and pain, risk of infection and recovery time. However, several methods can be used to dehorn large cattle if necessary, including large gouges, keystone or guillotine dehorners, hand saws, or obstetric (embryotomy) wire.

Tippinginvolves cutting a portion of the horn off an older animal but not completely removing it. This technique can also cause pain and bleeding, but is typically viewed as less invasive and painful than other methods. Tipping reduces the risk of puncture injuries due to sharp horns, but is less effective at reducing bruising.

Managing Pain

Managing pain in cattle is a public concern and a producer priority. Pain, stress, recovery time and complications are minimized when dehorning is performed early in life. Several methods can be used to reduce the pain of dehorning, including anesthetics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

The following webinar discusses the pain management methods for dehorning (29:51), requirements under the Code of Practice for Beef Cattle (30:09), and local anesthetic methods (33:12).

An anesthetic (e.g lidocaine) is a drug that temporarily eliminates all feeling. Local anesthetics cause numbness; general anesthetic cause unconsciousness. Anesthetics used to block the cornual nerve should ideally be injected 5 to 20 minutes before dehorning for maximum benefit to the animal and operator, although injection even a few minutes prior to the procedure still helps manage the pain quickly and can provide several hours of pain relief.

An analgesic or NSAID (i.e. Metacam and numerous others) temporarily eliminates pain, but not normal sensation. Analgesics are longer-acting than anesthetics, and may provide some pain relief for up to one day after dehorning by reducing swelling and pain.

According to recent surveys, between 27-31% of Canadian producer respondents indicated they always use pain control for dehorning. Between 14-23% of producers reported using pain medication depending on age and method of dehorning.

Potential Complications

Wounds usually heal well with no treatment, but there is a risk of complications such as uncontrolled bleeding, fly contamination, and bacterial infection. Calves require observation for bleeding for 30-60 minutes after dehorning. Coagulants like blood stop powder, tourniquets, clamps or hot iron cauterization can help to reduce blood loss. A fly repellent is recommended, and producers should watch for signs of infection for 10-14 days after dehorning.

References

Goonewardene, L.A., Pang, H., Berg, R.T., and Price, M.A. 1999. A comparison of reproductive and growth traits of horned and polled cattle in three synthetic beef lines. Canadian Journal of Animal Science, Volume 79, pages 123-127.

Neely, C.D., Thomson, D.U., Kerr, C.A., and Reinhardt, C.D. 2014. Effects of three dehorning techniques on behavior and wound healing in feedlot cattle. Journal of Animal Science, Volume 92(5):2225-9.

Feedback

Feedback and questions on the content of this page are welcome. Please e-mail us at info@cattlemaster

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Dr. Eugene Janzen for contributing his time to reviewing this content.

Expert Review

This content was last reviewed October 2019.

This content was last reviewed June 2023.