Forage establishment is a long-term investment requiring careful planning, preparation, species selection and management to ensure success. Proper establishment of the for-age stand plays a vital role in stand productivity and longevity. Begin planning at least 18 months prior to seeding forages to effectively control weeds and assess and manage soil pH and fertility. It is also important to consider the end use of the forage, whether for grazing, stored feed or both.

| Key Points |

|---|

| Selecting the Right Forage |

| • Choosing which forage species will depend largely on when and how a producer wants to utilize the stand. The species chosen may change depending on many factors, including the environment, field characteristics, intended use (silage, baleage, dry hay or pasture), frequency of harvest and desired length of stand life. |

| • Where possible, preserve and maintain native species; choose lands for new forage establishment that would benefit from having perennial cover, such as areas prone to excess moisture, or run-off and erosion |

| • High quality Certified seed is recommended as it provides legal guarantees for varietal purity, germination, and freedom from impurities such as weed seeds |

| • Companion or nurse crops can be useful in suppressing weeds and reducing erosion, provide protection from the elements for forage stand establishment, and provide extra feed during the first year when cut early as silage or greenfeed |

| Soil pH and Fertility |

| • In Eastern Canada, plan to apply and incorporate lime based on soil test results. The acidity of a field can impact nutrient availability and efficiency of fertilizer applied. Correcting soil pH to 6.0 – 7.0 can improve forage stands, nutrient availability and soil microbiology. |

| • Forage seed, liming agents and fertilizers can be costly; aim for success by creating a plan or working with an agronomist to create one for you. Ensure the plan addresses fertility demands for the crop and yield goals while also addressing soil pH, where required. |

| • Nutrients like nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K) and S, as well as many more, play important roles in plant growth and development. Address soil deficiencies and crop demands to improve germination and stand establishment and limit declines in stand productivity. |

| Successful Seeding |

| • Moisture and proper seed depth are the most important factors in successful germination and establishment of forage crops. The timing of planting and weed control are vital to ensure moisture for the seedlings. A well-prepared seedbed and a properly adjusted seeder can improve seed-to-soil contact and seed placement. |

| • If conditions are not conducive to spring seeding, summer seeding is also an option. It’s important to time summer seeding with forecasted rainfall to improve chances of establishment. In Western Canada, fall/winter dormant seeding is another alternative timing option. |

| • Weed control in prior crops can impact establishment success. Consider crop rotations and weed control that will reduce the weed seed bank. Control for weeds such as Canada thistle, quack grass, and dandelion prior to planting, as they compete for moisture and nutrients and can be difficult to control after seeding. |

| • Improper seedbed preparation is another leading cause of poor stand establishment. Forage seeds are often small and light; an ideal seedbed should be smooth, well-packed, moist and weed free to provide critical seed-to-soil contact and proper seed placement for successful germination. |

| • Use local sources for seeding rate information. Seeding rates vary from one species to the next and can change depending on soil zone and/or province as well as whether seeding a pure or mixed stand. |

| Maintenance of Forage Stand |

| • Manage the new stand carefully, with no grazing in the first year. Second year yield potential will depend upon forage species chosen and level of establishment success. Utilize new stands with a “take half, leave half” mentality and ensure fields are well rested before grazing again. Re-seed bare spots and monitor for weeds and pests. |

Selecting the Right Forage

Before selecting forage species, land managers must carefully consider the long-term needs and plans for the forage stand and how it will be used within their operation. Envi-ronmental factors, field characteristics, intended use and desired stand life will impact forage species selection.

Planning is key. Start at least 18 months prior to seeding to allow time for proper species selection, weed control, seedbed preparation, soil tests and pre-seeding fertilization. Perennial stands will usually be in production for many years, so treat it like a long-term investment. Environmental factors, intended use and stand life will impact forage species selection. Consider the land type, forage needs and utilization for the stand.

Review and contact local resources to find forage species suited for your needs. The Forage U-Pick tool is available and provides information on species used in both Western and Eastern Canada.

Consider the following:

- What is the intended use and when is the preferred season of use? Will it be pasture, sileage or hay? Will it be used for spring grazing, or cut for silage or baleage, made into hay, or kept for fall or winter grazing?

- For grazing, what is the management system? Will it be rotational, continuous or mob grazing?

- How often will it be harvested?

- How long will the stand be in production?

- What are the specific environmental conditions, soil type(s), annual precipitation, winter temperatures and problem areas such as prone to drought, flooding, run-off, alkaline, acidic, saline or stony areas?

- What are the specific herd needs?

- Is a single species or a species mixture (two or more species) better suited to the requirements and environment? Can native species be used?

Intended Use of the Forage Stand

Forages vary in their suitability for stored feed production, like silage and hay, as well as pasture based production and the different management strategies of pasture. Consider the use, frequency and type of harvest when determining stand composition. Native species, crested wheatgrass and low-growing forages such as white or Kura clover or kentucky bluegrass are not well suited to mechanical harvesting and are better utilized as part of a grazing system. Alfalfa, on the other hand, typically does not tolerate frequent grazing without stand loss, and unless managed carefully may be more suitable for making silage or hay. Some forages are suitable for haying and include smooth and hybrid brome grasses, rye grasses and timothy. While others like red clover, orchardgrass and tall and meadow fescue, may fit better in silage or baleage systems. How a stand will be managed will help determine species selection as certain species perform better under different conditions. Some exceptions occur but are variety specific and may require consultation with seed suppliers.

Timing of Use

Selection of the forage species will depend largely on when and how a producer wants to utilize the stand. Forage species vary in seasonal growth patterns, yield, nutrition levels and regrowth response to grazing or mechanical harvest. Crested wheatgrass is an early season grass which could be suited to early turn-out at calving, or for pairs following calving. Alfalfa’s growth pattern can fit well with rotational grazing, using rapid, even grazing, followed by a long rest period. Although it tolerates close grazing or haying, it does not tolerate continuous grazing. Alfalfa also performs well in multiple-cut silage and hay systems along with orchardgrass or fescues. Timothy is suited to one- to two-cut hay systems but does not tolerate con-tinuous grazing. As with all species, native plants should be grazed during their optimal growth period and when growing conditions are favourable. Rest and recovery are the most important aspects when determining timing of use.

Single Species or Mixture?

To determine whether a single species or a mixture provides the best option for the new forage stand, producers should consider many factors. Single species work well for single end uses, while mixtures, such as grass-legume blends can provide more options, such as harvesting for hay or silage as well as grazing, but some with increased complexity in management. To increase protein levels and digestibility of forage, producers often consider forage mixtures that contain a legume such as red clover, birdsfoot trefoil, or alfalfa. Grass species that grow well when planted with alfalfa include: meadow bromegrass, timothy, crested wheatgrass, orchard grass and tall fescue. Mixtures containing 30-40% legume can usually produce enough nitrogen to meet the forage stands’ requirements, reducing the need for regular applications of nitrogen fertilizer. Grass-alfalfa mixtures can reduce risk of bloat, while increasing the length of the grazing season.

Research conducted by Dr. Yousef Papadopoulos at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s Experimental Farm in Nappan, Nova Scotia examined four different pasture blends. The combinations consisted of timothy, meadow fescue, reed canarygrass, Kentucky bluegrass, tall fescue, meadow brome and orchard grass with either birdsfoot trefoil or alfalfa. Yields were higher with the alfalfa blends, yet animal performance was better on the blends containing trefoil. Over the five years of the trial, both legumes declined in the stands, affecting both yield and performance. Results are highly variable and forage mixtures may exhibit different results across the many regions of Canada.

Longevity and yield of a forage stand begins with choosing a variety adapted to the intended use, environment and field conditions. High quality Certified seed is recommended as it provides legal guarantees for varietal purity, germination, and freedom from impurities such as weed seeds.

In the following webinar, Dr. Surya Acharya discusses new forage varieties and research at Agriculture Agri-Food Canada Lethbridge Research and Development Centre.

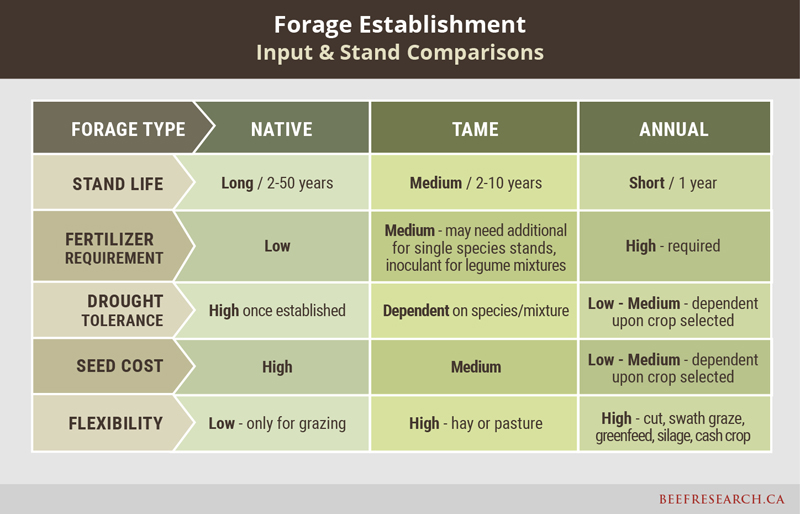

Tame vs. Native Grasses

While tame forage species are often the first choice for producers establishing a new stand due to lower cost, seed availability and faster establishment, native species can outperform in certain growth limiting environments over the long term once well established. Under optimum conditions, tame forages can have higher yields, and offer flexibility in terms of cutting for silage, hay, or swath grazing, while native rangelands and pastures on marginal lands exhibit drought tolerance and resilience.

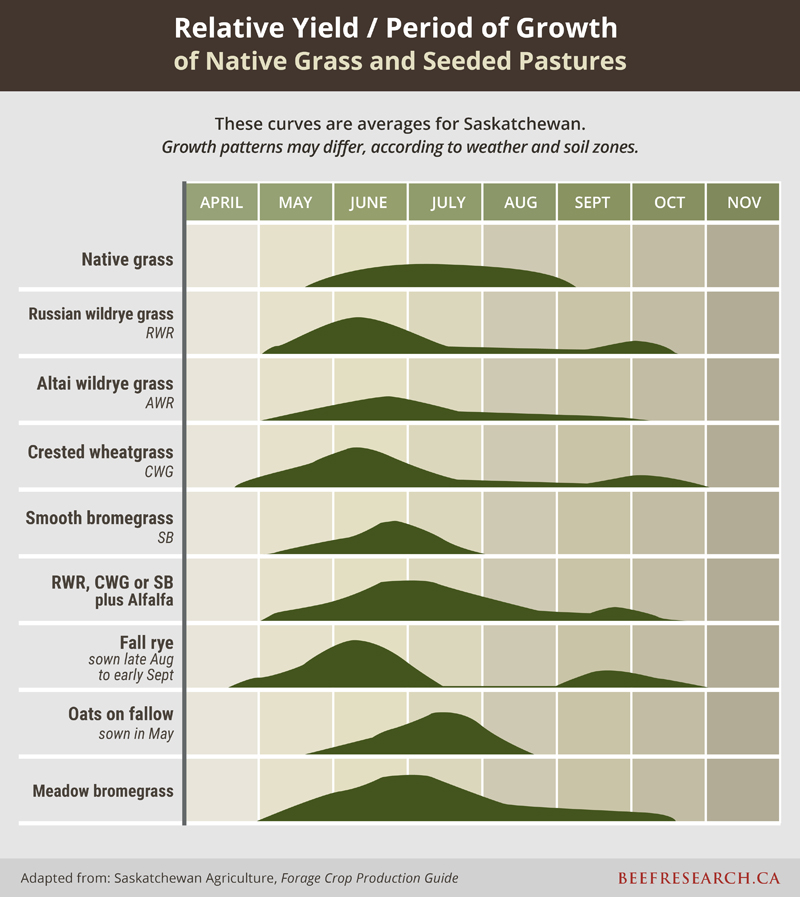

Where possible, preserve and maintain native species; choose lands for new forage establishment that would benefit from having perennial cover, such as areas prone to excess moisture, or run-off and erosion. Producers on mixed operations must consider the opportunity cost of higher valued land when it is seeded to forages. Less productive land is often a better fit for establishing or re-establishing native stands. The table below illustrates yield and period of growth of native grasses in Saskatchewan, relative to several common tame grasses and annuals.

Seeding Annual Crops as Forage

Seeding annuals, such as barley, oats, peas, triticale or ryegrass as a forage source can provide additional feed, tonnage or grazing flexibility. Annuals can provide a period of rest and recovery for perennial pastures, as well as supplemental feed during drought, or late seeding options when excessive spring moisture prevents normal timing for seeding. Fall seeded winter cereals can be grazed in mid-May, reducing pressure on other pastures. Annuals can also extend the grazing season and provide excellent quality feed if grazed or cut for greenfeed hay, swath grazing or silage.

The inclusion of a field or forage pea can boost protein levels. Intercropping involves planting a spring cereal with a winter annual, allowing the flexibility to harvest the spring cereal for silage, and leave the winter cereal for mid to late season grazing.

Another use of annuals is as a cover crop or emergency forage. They can provide a quick-growing source of forage and can be grazed or harvested in the season they are planted. There is much interest in cover crops/poly crops by both livestock producers and farmers as a feed source and a means to improve soil properties. Research is ongoing in this area.

The following table summarizes key characteristics and comparisons of native, tame, and annual forages.

Companion Crops

Companion or nurse crops can be useful in suppressing weeds and reducing erosion, can provide protection from the elements for forage stand establishment, and may provide feed during the first year when cut early as silage or greenfeed. Remember that a companion crop will always compete with the forage crop for nutrients, light and moisture. They may lead to thinner stands, may impact the survival rate of the establishing crop and can reduce yield of the forage stand either in the establishment year or subsequent years. Selection and management of the companion crop is important to minimize competition with the forage species chosen. The field should be managed for the forage crop, not the companion crop. Seeding rates for companion crops are suggested to be half to one third of the normal rate to reduce competition 1, 2. Timing of the removal of the companion crop, whether harvested for silage, greenfeed or grain, is important as well as the longer a companion crop is kept, the greater the competition for resources.

The suitability of establishing perennial forage with companion crops varies depending on the local growing and weather conditions. The suitability of forage species to companion cropping also varies across the country. It is recommended producers review local production information, whether guides or provincial webpages for specific species information. In Atlantic Canada it has been noted that “forages such as red clover, timothy and rye grasses seem to establish better in a companion system than alfalfa and most other grasses (Atlantic Forage Guide)3.”

• Manitoba, Tips for Improving Forage Establishment Success. Government of Manitoba.1

• Alberta Forage Manual2

• OMAFRA, Publication 30, Guide to Forage Production4

In drier regions, success with companion crops is limited. Research at three sites in Saskatchewan over a three-year period examined the use of annual crops such as field pea, canola and ryegrass as companion crops. The economic returns were worse with a companion crop at two locations, Swift Current and Saskatoon, but slightly better at Nipawin5. This research demonstrated that the feasibility of companion crops for establishment of short-lived perennial forages in Saskatchewan depends on soil zone, with the more humid areas being the best suited to this practice.

Another study using two sites in Saskatchewan assessed the suitability of annual ryegrass and festulolium as companion crops when used during establishment of perennial forages in pure and mixed stands. It was found that both species can be used as companion crops for establishing perennial forages in the prairie region of Western Canada. Stand densities of the perennial forage crop were lower for most treatments in Saskatoon but not impacted in Melfort. Yield during the establishment year was improved with the use of companion crops. Yields were lower in the following year but the compan-ion crop usually did not impact yields in year 2 after establishment. The 3-year total yield was usually not impacted by the use of the companion crops.6 This study did not look at the economics of a companion crop, however it reinforces that they can successfully be used, with some impact depending on soil zone, and are a way to improve establishment year yields.

Soil pH and Fertility

Conducting a soil test to identify nutrient deficiencies and soil pH. Determine the nutrient requirements for the selected forages based on local sources. Create a pre-seeding soil fertility plan that enhances germination and establishment. Do so by correcting soil acidity, if needed, and adressing possible nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium and sulphur deficiencies.

Soil pH – Depending on the soil test results and chosen forage, soil pH should be cor-rected using a liming agent to bring the range up to 6.0 – 7.0. Acidic soils can limit nutri-ent availability to forages leading to reduced yield potential despite fertilizer application. It can also impact the survivability and productivity of some beneficial micro-organisms, like nitrogen fixing bacteria, which further limits legume growth and nitrogen contributions to grasses if sown in a mixture. Available liming agents may differ across regions.7 In East-ern Canada, calcitic (CaCO3) or dolomitic (CaMg(CO3)2) limestone are typically used as liming agents. Choosing the right liming agent is important as they not only neutralize soil pH but can also provide nutrients like calcium (Ca) or magnesium (Mg) to varying de-grees. The best choice of liming agent will depend on soil test results, local availability, coarseness and price. For questions about which liming agent to use, contact a local agronomist for more information.

Fertility – Nutrient requirements will differ based on the forage species, expected yield and current soil fertility and production systems. Identify the costs and time needed to amend soil or correct deficiencies. If soil tests reveal significant deficiencies that would be too costly or prohibitive to correct, alternative species selection may be required. However, understand that depending on corrective actions needed and production plans, not acting may mean a bigger bill in the future. Work with a local agronomist to create a plan based on recent soils tests. This can help ensure a plan that meets crop nutrient demands while considering cost constraints. Consider the 4R’s – use the right source, at the right rate, the right time, and the right place.

Forage seed and fertilizers can be costly; plan for success by having a Professional Agrologist conduct soil tests and create a fertilization plan for the forage stand.

Farmers should take soil tests every three to four years to determine if fertilizer or liming agents should be reapplied. Fields under a grazing system will have nutrients returned by the manure and urine of grazing animals, although depending on management practices the nutrient distribution may not be ideal and may be concentrated in high traffic areas or near shade. Farmers harvesting and removing forage from the field will need to replenish lost nutrients from each harvest whether through application of manure, compost or ferti-lizers.

Nutrients – Nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P) potassium (K) and sulphur (S) are key nutrients to test for and supplement, if needed, prior to establishing a new forage stand. Produc-ers often cite declining productivity within their forage stands as the reason for termina-tion and re-establishment of a stand. Producers can improve stand establishment and yield by ensuring that the nutrient levels are adequate for the species selected. Macronu-trients calcium (Ca) and magnesium (Mg) are required for alfalfa growth but are usually available in adequate amounts in Western Canada8. In Eastern Canada, calcium and magnesium often need to be supplemented through lime or other soil amendments. Mi-cronutrients such as boron, copper, manganese or zinc, may also be required but should only be applied at the recommendation of an agronomist based on soil tests.

Nitrogen

Nitrogen (N) assists with plant growth and yield. Ensure that nitrogen levels are adequate prior to seeding to provide enough nutrition for the seedlings to have healthy emergence and establishment. The forage species selected will determine the nitrogen requirements based on soil tests.

Pure stands of perennial grasses are more prone to nitrogen deficiency than mixtures that contain legumes like alfalfa, clovers or birdsfoot trefoil, which can fix atmospheric nitrogen when properly inoculated. Pure legume stands or grass-legumes mixtures with greater than 30% legumes do not require applications of nitrogen fertilizer as the pres-ence of nitrogen may impede formation of nodules and reduce N-fixation capabilities of N-fixing micro-organisms. Grass-legume stands with 30% or less legumes may require nitrogen fertilizer application to improve grass productivity. The addition of legumes can boost productivity and value of the stand, as costs and demand for nitrogen are reduced.

Pure grass stands may benefit from nitrogen applications for optimum production during the life of the stand, provided adequate moisture exists to achieve a positive response. Variables such as fertilizer and hay prices impact the benefit received from fertilization.

Applying the total nitrogen required at one time can increase risk of loss through volati-lization or run-off and is not recommended in Eastern Canada. Splitting the application of nitrogen can reduce losses and diminish damage to seedlings, which can be injured by high amounts of N. For split applications, nitrogen should be applied early in spring and as close to harvest as possible to improve regrowth4, 9.

Sources of nitrogen can include urea-ammonium-nitrate (UAN), urea, and anhydrous ammonia. Urea can be broadcast, (spread on top of the ground) banded (injected or drilled into the ground), or incorporated at seeding with certain seeding equipment. Refer to local agronomic guides for recommended fertilization rates or consult with a local agronomist.

Phosphorus

Phosphorus (P) plays a vital role in root development and is important for establishment of a new stand. Phosphorus is immobile in soil, meaning that the fertilizer needs to be placed 2.5 centimetres below and 2.5 centimetres to the side of the seed. For this reason, broadcasting phosphorus during the year of establishment is not recommended. Banding is preferred at seeding. If long term planning has occurred and soil tests indicated low P levels, broadcasting for one or two seasons prior to establishment can be effective, as the P becomes incorporated into the soil over time and will then be available at seeding. Many soils across Canada have phosphorus deficiencies. Soil pH is very important to phosphorus, with a target pH of 6.5 – 7.0. At higher and lower values, phosphorus availability is reduced, compromising establishment and healthy root development.

Potassium

Potassium (K) is responsible for root development and yield, stand persistence, disease resistance and winter survival. Potassium can be limiting on lightly textured grey soils, and deficient in sandy, intensively cropped soils. Banding or broadcasting potassium fertilizer are both effective ways to apply potassium. Grasses do not require as much potassium as mixtures containing legumes or pure legume stands. When forages are cut as sileage or hay, significant amounts of potassium are removed from the soil. Sandy loam soils in particular demonstrate both a yield and protein response to K application. Ensure adequate levels prior to planting, and repeat soil tests annually to ensure optimal levels are maintained.

Sulphur

Sulphur (S) is required for nitrogen fixation by legumes and for protein metabolism. If incorporating alfalfa into a forage blend, sulphur is an important nutrient to test and manage for since it directly impacts yield and protein levels. Deficiencies are common across Canada on well-drained sandy soils, grey wooded soils and soils with low organic matter10. Sulphur can be more difficult to test for prior to seeding a new forage stand, as the most accurate measurement of sulphur content is determined through plant tissue testing. Alfalfa requires and removes more sulphur than pure grass stands, so it should be considered for mixed blends containing alfalfa. Low pH levels also make sulphur unavailable to the plant. Visual symptoms of a sulphur deficiency can be similar to nitrogen deficiency and will include stunted plants with reduced internode growth and yellowing of leaves.

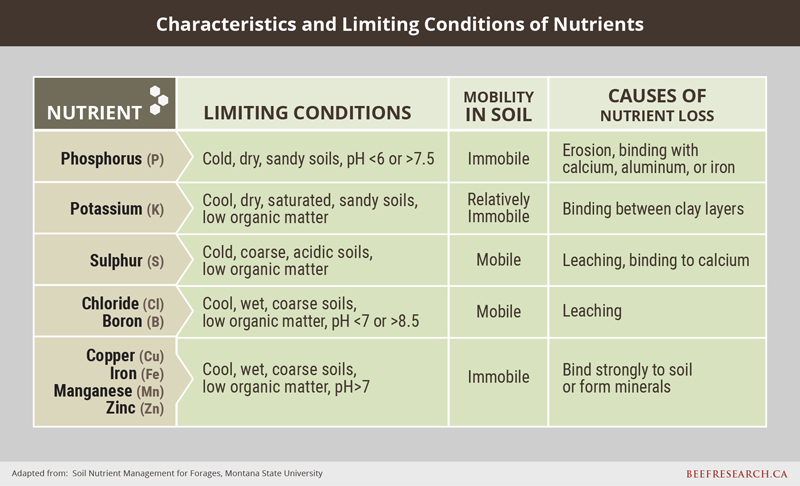

Certain conditions can limit key nutrients and micronutrients available to the forage, impacting yield and health. Soil tests that identify these conditions can alert producers to potential issues. The following table identifies limiting conditions.

Successful Seeding

Timing of Seeding

Moisture is one of the most important factors in successful germination and establishment of forage crops, so proper timing and weed control are vital to conserve moisture for the seedlings. In most areas, early spring seeding produces the best results because adequate moisture is usually available, temperatures are conducive for germination and weed pressure may be limited. In areas with less precipitation, direct seeding into stubble is an effective way to preserve moisture to enhance germination and to provide some shelter for emerging seedlings from harsh, drying winds. Areas with excessive moisture can utilize frost seeding or later season planting to avoid soil compaction.

If conditions are not conducive to spring seeding, summer seeding and fall/winter dormant seeding provide alternative timing options. Frost seeding usually occurs in early spring, just prior to frost coming out of the ground, and takes advantage of the freezing and thawing of the soil to work seeds into the soil. Frost seeding is typically used to introduce new legumes into an established forage stand or as a renovation practice to improve forage coverage of bare spots. Due to the potential for excessive moisture conditions in spring, which can force producers to seed later than desired, some areas in Manitoba and the Maritimes use broadcast or frost seeding to establish fields. Late fall seeding carries a risk that the seedlings may not build up sufficient nutrient reserves to over-winter successfully. If using dormant or frost seeding techniques, increased seeding rates are recommended to offset seed and seed-ling mortality. Seeding rates can be reduced to 1/3 of their recommended seeding rate if broadcasting into an established stand or when using a mixture instead of a single spe-cies. In Western Canada, fall dormant seeding (seeding in late fall before the ground freezes), works well if direct seeded into stubble at a soil temperature below 2C which prevents germination until spring.

Weed Control

Weed control in prior crops can impact establishment success. Consider crop rotations and weed control that will reduce the weed seed bank. Control weeds such as Canada thistle, quack grass, and dandelion prior to planting, as they compete for moisture and nutrients and can be difficult to control after seeding. If using manure as a nutrient source, be aware that it may also introduce viable weed seeds. Ideally, manure would be applied the year prior to allow time for weed seed germination and control before planting the forage stand. Ensure that any herbicides applied in recent years will not have a residual effect that can impact germination of the forage seedlings being established, whether tame or native, grass or legume. Refer to crop production or plant protection guides and check labels or contact the manufacturer for more information.”

Alfalfa Autotoxicty

If re-seeding alfalfa into an existing or recently terminated alfalfa stand, autotoxicity must be managed for. The cause of alfalfa autotoxicity is still being researched, however the result is that the produced compound(s) can have a negative impact on alfalfa new seed-ling emergence and their growth and performance. This becomes a problem when at-tempting to reseed alfalfa into an existing stand, or one that has been reduced by winter-kill or flooding and is why these practices are not recommended. Some, but not all, fac-tors that can affect the length of time in which these autotoxic compounds may have an impact on a subsequent seedings of alfalfa include soil characteristics, rainfall, length of time between termination of an old alfalfa stand and the new seeding and tillage meth-ods.11 12 13 A general rule is to wait at least 12 months before seeding alfalfa back into a field that previously grew alfalfa. It is also recommended to grow another crop on this field. The cultural practices and length of time should allow sufficient time for autotoxic compounds to breakdown or be removed from the field through rainfall or irrigation allow-ing the future alfalfa crop to avoid reduced plant vigour and lower yields.11 12

Seedbed Preparation

Improper seedbed preparation is another leading cause of poor stand establish-ment. Forage seeds are often small and light; an ideal seedbed should be smooth, well-packed, moist and weed free to provide critical seed-to-soil contact and proper seed placement for successful germination. Excess straw or residue on the field from prior crops can impede seed-to-soil contact and negatively impact germination. When planning 18-24 months in advance of seeding the forage crop, harvest methods in the prior years can include baling extra straw, harrowing or ensuring that the straw is well chopped and spread coming out of the combine. Seeding equipment that provides proper depth and seed placement generally yields better results than broadcast methods; prop-er depth is key.

Seeding Depths and Rates

Information related to seeding depth and rates for Western and Eastern Canada are pro-vided below. Please go to the appropriate section.

Seeding in Western Canada

Recommended Seeding Depths in Western Canada

• Seed 1/4” – 3/4” (0.65 – 1.25 cm) deep in fine textured, clay soils, and if forage seeds are small (e.g., timothy)

• Seed 1/2” – 1” (1.25 – 2.5 cm) deep in loam

• Seed 3/4” – 1 1/2” (2 – 3.75 cm) in sandy soils

• If a broadcast method is used, roll or harrow pack afterwards to improve seed-to-soil contact.

Seeding rates will depend on the type of forage, soil type, moisture availability, the de-sired number of plants per square foot or square metre, and the type of seeder used. Plant populations and seeding rates should increase with increasing soil quality and available moisture.

Seeding rates in Western Canada

In Western Canada the target Pure Live Seed (PLS) densities are:

• 18-20 seeds/ft2 (15-16 seeds/m2) PLS in Brown soil zone

• 20-25 seeds/ft2 (16-20 seeds/m2)) PLS in Dark Brown soil zone

• 25-30 seeds/ft2 (20-24 seeds/ m2) PLS in the Black/Grey Wooded soil zone

• 30-40 seeds/ft2 (24-32 seeds/ m2) PLS under irrigation

Row spacing in forage stands is generally recommended at 12-14 inches (30-35 centi-metres) and 6 inches (15 centimetres) under irrigation and in Eastern Canada.

To calculate the seeding rate in pounds per acre (or kilograms per hectare) multiply the target seed density by 43,560 square feet in an acre (or by 10,000 square meters in a hectare) and divide the total by the number of seeds in a pound (or kilogram) of the spe-cific species chosen. Each species will have a different number of seeds per pound or kilogram. To find the species-specific seeds per pound or seeds per kilogram value, please see the excel file at the bottom of the Forage U-Pick Seed rate calculator page.

For example, using the Dark Brown soil zone with certified seed of 79% germination and 98% purity, the Pure Live Seed would be:

Pure Live Seed = Germination% X Purity %

= (0.79 X 0.98)

= 0.77

Seeding Rate (lbs/ac) = seeds/ft2 X ft2/acre / PLS

seeds/lb

= 22 seeds/ft2 X 43,560 ft2/acre / 0.77

200,000 seeds/lb

= 4.79 lbs/acre / 0.77

= 6.2 lbs/acThe factsheet Successful Forage Crop Establishment, reprinted with permission from the Saskatchewan Forage Council, provides more detail on seeding calculations.

Seeding in Eastern Canada

Recommended Seeding Depths in Eastern Canada 14 15

• Seed 1/4” – 1/2” (0.65 – 1.25 cm) deep in clay and loam soils

• Seed 1/2” – 1” (1.25 – 2.5 cm) deep in sandy soils

Seeding rates will depend on the type of forage, soil type, moisture availability, the de-sired number of plants per square foot or square metre, and the type of seeder used. Plant populations and seeding rates should increase with increasing soil quality and available moisture.

Seeding rates in Eastern Canada

Seeding rates in Eastern Canada are provided as a range either in kg/ha or lb/acre and will vary from one species to the next. Some species-specific seeding rate ranges are found in the below table. The species identified in the table are due to general popularity and are not a specific endorsement of suitability or preference.

| Species | Ontario pure stand reccomended rate kg/ha (lb/acre)4 | Quebec pure stand reccomended rate kg/ha (lb/acre)16, 17 | Atlantic Canada pure stand reccomended rate kg/ha (lb/acre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alfalfa | 13 – 22 (11.5 – 19.5) | 14 (12.5) | 15 (13.5) |

| Red clover | 12 -15 (10.5 – 13.5 ) | 10 (9) | 11 (10) |

| White clover | 4.5 (4)* | 4 (3.5)* | 5 (4.5) |

| Alsike clover | 3 (2.5)1 | 10 (9)1 | 9 (8) |

| Birdsfoot Trefoil | 2 – 9 (1.5 – 7) | 10 (9) | 9 (8) |

| Fescue (Meadow & Tall) | 9 – 11 (8 – 10) | 16 (14) | 15 (13.5) |

| Timothy | 8 – 10 (7 – 9) | 10 (9) | 8 – 10 (7 – 9) |

| Orchardgrass | 7 – 9 (6 – 8) | 11 (10) | 8 – 10 (7 – 9) |

| Perennial Ryegrass | 22 – 44 (19.5 – 39) | 20 – 35 (18 – 31) | 12 (11) |

When seeding pre-mixes from seed suppliers, use the provided seed rates from the company, however, if this is not provided or if producers choose to, they can calculate their own seeding rate. To do this, a rate must be identified for each species within the mix and, when those values are added together, the final value will be the seeding rate for that mix. Another method is to use the BCRC seeding rate calculator found with the Forage u-pick tool. For calculating each species by hand, use the following calculations:

Pure Live Seed (% PLS) = [Germination% X Purity %]

Species seeding rate in kg/ha or lbs/ac: [(Recommended seeding rate for a pure stand of that species in kg/ha or lbs/ac X % PLS) X % of species in the mix]

Actual seeding rate in kg/ha or lbs/ac: [Species seeding rate in kg/ha (lbs/ac) X overage factor]

Note: The overage value can depend on a variety of factors including direct or sod seeding, drilled vs broadcasted, soil conditions, and others. See local resources for overage recommendations.

Producers seeding forage stands under irrigation, or in zones/regions with adequate moisture have more flexibility in seeding methods and equipment. In high moisture areas, broadcasting seed may be the best option. Harrow/packing and timely rain or adequate moisture will determine success with broadcast methods. If using hoe drills, double disc press drills, air seeders or packer seeders, be aware of common issues with each. For example, forage seeds can be small and fluffy, causing bridging in seeders without an agitator. Press drills pack the seed well for soil-to-seed contact, but discs sometimes cannot penetrate straw on the surface, while hoe drills can bunch up any excess straw or crop residue in front of the shanks and plug, creating missed runs. Air seeders and drills can seed a large area, have good trash clearance and depth control for small seeds. The seed is packed well for good contact and germination. Because the forage seed is so light, the fan speed must be kept lower to avoid blowing the seed out of the furrow. Packer seeders may also be used however they do not perform well on very hard or sandy soil.14 Packer seeders may also have issues if used in dry conditions as they may not be able to place seed into moisture.

Some producers report that their cattle have consumed the seed pods of legumes such as cicer milkvetch and sainfoin, and distributed them across pastures in the manure, where the seeds then germinated. While this method is unpredictable, it may be a way to slowly increase legumes in a stand.

Economics

The decision to establish a new forage stand requires research into species selection, timing of use, plus many other factors described above. The economics of the decision should be analyzed prior to establishment.

Costs include:

- seed

- fertilizer and crop nutrition inputs

- soil amendment products, trucking and spreading costs

- weed control inputs, herbicide

- equipment rental, custom seeding

- maintenance costs over life of stand (i.e. weed control, fertilization, rejuvenation)

Compare and contrast those costs with:

- days of grazing and estimated animal performance or custom pasture rental income

- market cost and estimated yield if making baleage or dry hay and selling forage as a cash crop

Maintenance of Forage Stand

After successfully seeding and establishing the new forage stand, consider the following best management practices to ensure ongoing success and production of the new stand. Whether focusing on stored feed such as silage, baleage or dry hay or on grazing, consider weed control and maintaining soil nutrient requirements to maximize your investment. For graziers, make sure to update or design a grazing management strategy that best utilizes the new stand.

Be alert to any insect or disease pressure that might compromise establishment and stand longevity. Grasshoppers can be problematic in dry areas of the Prairies, while the Maritimes may have European Skipper infestations on timothy, perennial ryegrass and meadow fescue. Armyworms and potato leafhoppers are often seen affecting forages in Ontario and Quebec.

In this picture, armyworms ate all the pasture grasses, leaving only broadleaf weeds behind.

For graziers, manage the new stand carefully, with no grazing in the first year. Second year grazing potential will depend upon forage species chosen and level of establishment success. Utilize new stands with a “take half, leave half” mentality. Re-seed bare spots and monitor for weeds and pests20.

In the establishment year:

- grazing is not recommended

In the second year after establishment:

- grazing will depend upon forage species chosen and level of establishment success. The ‘take half, leave half’ concept helps to ensure root development is not compromised by removing too much plant material too early

- assess and control for weeds as necessary

- fill any bare spots that did not establish by broadcasting new seed on those areas

- soil or tissue test to ensure adequate soil fertility, top dress with fertilizer if necessary

- monitor for insect pressure that could reduce the stand while it is still establishing

For stored forage production, in the establishment year:

- one cut may be taken late in summer. Cutting height should be kept high, greater than 6 inches and timed to allow adequate recovery prior a killing frost.

In the following years:

- schedule timing of harvest based on desired product, whether silage, baleage or dry hay, remembering to account for forage quality needs

- change cutting height based on environmental conditions. Cut higher in drought years to allow faster recovery. Do not cut below 3 or 4 inches (7.5 – 10.2 cm)

- manage weeds carefully, either through cultural methods or by chemical control. If using chemicals, be aware of harvest and feed restrictions

- fill bare spots by broadcasting new seed

- soil or tissue test to assess soil fertility and make ongoing fertilizer plans

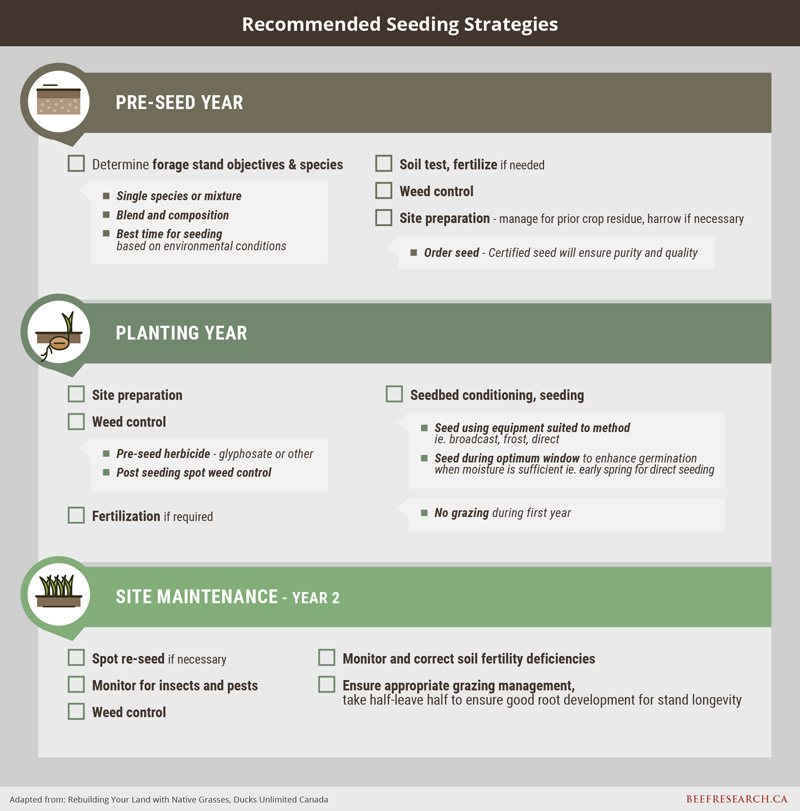

The following table, adapted from Rebuilding your land with Native Grasses, provides an overview of the process for successful forage establishment5.

Conclusion

The long-term nature of forage crop stands requires careful planning to ensure proper species selection for the intended use, as well as successful establishment and maintenance. While native forage stands can be more costly and slow to establish, they generally require less long-term management in terms of fertility. Several research studies indicate a net benefit to including a legume in a forage stand, both in terms of feed value and overall economics of forage production. Grazing management strategies will play a role in determining forage species selected and the ongoing success and productivity of the stand. Regional variation in soil types and climatic conditions necessitates soil testing to determine any necessary soil amendments or fertility inputs and correcting deficiencies prior to seeding. Correcting soil deficiencies can improve stand productivity and longevity. Soil characteristic and weather patterns also plays a significant role in the determination of the best single, binary, or complex mixture to plant. Ensuring a clean field through weed control, enabling good soil-to-seed contact through proper seed bed preparation and using the appropriate seeding rate will enhance germination and establishment. For new stands, managing harvest pressure (grazing or mechanical), insects and weeds will be especially important in the first couple of years to ensure a productive and long-lived stand. Established fields and pastures should have soil tests completed periodically (3 to 5 years) to identify whether fertilizer or lime need to be re-applied to help keep them productive for years to come.

- References

-

1 Tips for Improving Forage Establishment Success. Government of Manitoba. Url: https://www.gov.mb.ca/agriculture/crops/crop-management/forages/print,tips-for-improving-forage-establishment-success.html

2 Arvid Aasen and Myron Bjorge. 2009. Alberta Forage Manual. Alberta Agriculture and Rural Development. 2nd edition.

Url: https://www.alberta.ca/forage-and-pasture-management.aspx

3 Atlantic Forage guide. Forage and Corn Variety Evaluatoin Task Group Atlantic Canada. Url: http://www.gov.pe.ca/photos/original/ag_atlforaguide.pdf

4 Guide to Forage Production, Publication 30. Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA). Url: https://www.ontario.ca/page/guide-forage-production

5 Jefferson, P.G., G. Lyons, R. Pastl, and R.P. Zentner. 2005. Companion crop establishment of short-lived perennial forage crops in Saskatchewan. Can. J. Plant Sci. 85: 135–146.

6 Coulman, B., A. Kleinhout and B. Biligetu. Annual ryegrass and Festulolium as companion crops in the establishment of perennial forage crops. Canadian Journal of Plant Science. 99 (5): 611-623.Url: https://doi.org/10.1139/cjps-2018-0238

7 Atlantic Soils Need Lime. Advisory Committee on Soil Fertility. Url: https://www.gov.nl.ca/ffa/files/publications-pdf-atlantic-soils-lime.pdf

8 McKenzie, R.H. 2005. Soil and Nutrition Management of Alfalfa.

9 Forage Production Guide. 2021. Updates from Perennia Food and Agriculture. Original: Advisory Committee on Cereal, Protein, Corn and Forage Crops (1991) Atlantic Provinces Field Crop Guide (Publicatoin No. 100 Agdex No. 100.32) Atlantic Provinces Agricultural Services Coordinating Committee

10 Mahoney, K., M. Sharifi, and J. Van Roestel. Survey of Sulphur Levels in Nova Scotia Soils.

11 Kim Cassida. 2019. Managing alfalfa autotoxicity. Michigan State University Extension. Url: https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/managing-alfalfa-autoxicity

12 John Jennings. Understanding Autotoxicity of Alfalfa. University of Wisconsin-Madison. Team Forage Division of Extension. Url: https://fyi.extension.wisc.edu/forage/understanding-autotoxicity-in-alfalfa/

13 Alfalfa Autotoxicity. Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA). Url: http://omafra.gov.on.ca/english/crops/field/autotox.htm

14 Agronomy Guide for Field Crops, Publication 811, Chapter 3. Forages. N.d. Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA).

15 Gilles Bélanger, Annie Claessens, Marie-Noëlle Thivierge et Gaëtan Tremblay (Éditeurs scientifiques). 2002. Chapitre 5 – Préparation du sol et Ensemencement. Guide de production – Plantes fourragères, 2e édition – Volume 1. Centre de référence en agriculture et agroalimentaire due Québec. 273p. ISBN 978-2-7649-0636-1.

16 Gilles Bélanger, Annie Claessens, Marie-Noëlle Thivierge et Gaëtan Tremblay (Éditeurs scientifiques). Tableau 5.1 Doses de semis pour les espèces fourragères pérennes au Québec. 2002. Guide de production – Plantes fourragères, 2e édition – Volume 1. Centre de référence en agriculture et agroalimentaire due Québec. 273p. ISBN 978-2-7649-0636-1.

17 Gilles Bélanger, Annie Claessens, Marie-Noëlle Thivierge et Gaëtan Tremblay (Éditeurs scientifiques).Tableau 5.4b Doses de semis pour les espèces fourragères annuelles utilisées comme plante-abri au Québec. 2002. Guide de production – Plantes fourragères, 2e édition – Volume 1. Centre de référence en agriculture et agroalimentaire due Québec. 273p. ISBN 978-2-7649-0636-1.

18 Maritime Pasture Manual, 1st ed. 2009. Url: https://www.perennia.ca/portfolio-items/forages/

19 Private conversation with Yousef Papad of AAFC, Nappan, NS.

20 Gabruch, L.K., J. Giles, C.G. Penner, and D.B. Wark. Rebuilding Your Land with Native Grasses. Url: https://www.saskforage.ca/s/Successful-Forage-Crop-Establishment.pdf

Feedback

Feedback and questions on the content of this page are welcome. Please e-mail us.

Expert Review

This content was last reviewed June 2023.

This content was last reviewed September 2023.