When you don’t know the quality of feed on an operation, maintaining animal health and welfare can become significantly more difficult. Visual assessment of feedstuffs is not accurate enough to access quality and may lead to cows being underfed and losing body condition, or wasting money on expensive supplements that aren’t necessary.

On this page:

- Why feed test?

- A Tool for Evaluating Feed Test Results

- Collecting Feed Samples

- Dry, Baled Forages

- Silage

- Bale Silage (Baleage or Haylage)

- Swatch Grazing and Standing Crop

- Grains, Pellets, By-Products and Alternative Feeds

- What Should I Test For?

- A Tool for Evaluating Feed Test Results

- Near Infrared Reflectance Spectroscopy (NIRS)

- Meeting Nutrient Requirements for Cattle

- Interpreting Lab Results

- Preventing Problems

- What About Water?

- Formulating Rations

- Interested in feed testing? What’s next?

- A Tool for Evaluating the Economic Value of Feeds Based on Nutrient Content

- Download Excel versions of the calculators

Understanding the quality of the feed being fed on a beef cattle operation is paramount to maintaining animal health and welfare. Visual assessment of feedstuffs is not an accurate means to assess quality and may lead to cows being underfed and losing body condition or result in overspending on expensive supplements that aren’t necessary. It is recommended that producers test feeds prior to feeding to ensure that the cattle nutritional requirements will be met.

| Key Points |

|---|

| Feed testing can assist producers in identifying potential issues that could result from nutrient imbalances. |

| It’s critical to collect a feed sample that is representative of the feed ingredient(s) that you are testing. |

| Samples should be taken as close to feeding or selling as possible, while leaving enough time for the results to come back from the lab. |

| Laboratory results are typically reported on both a “Dry Matter” and an “As-Fed” basis. Dry Matter (DM) refers to the moisture-free nutritional content of the sample. Always formulate rations on a DM basis. |

| Most labs provide basic information on moisture content, protein, energy, total digestible nutrients, fibre, and some vitamins and minerals. More specialized tests may include results for pH, acid detergent insoluble nitrogen ( ADIN), nitrates, toxins, relative feed value (RFV), and other parameters. |

| Trace minerals, particularly copper, zinc, and manganese, are important for the reproduction, health, and growth of an animal, and almost always require supplementation. |

| In most cases, it is recommended that minerals be supplemented year-round. |

| Testing stock water quality is particularly important during a drought, when minerals and nutrients may become concentrated as water tables drop in surface or ground water, or evaporation occurs in stock ponds. |

| Once feed test results are available, producers can formulate an appropriate ration for their cattle using the services of a qualified nutritionist, the assistance of agriculture extension staff, or through a software program such as CowBytes |

Why Should I Feed Test?

- Avoid sneaky production problems, such as poor gains or reduced conception caused by mineral or nutrient deficiencies or excesses;

- Prevent or identify potentially devastating problems due to toxicity from mycotoxins, nitrates, sulfates, or other minerals or nutrients;

- Develop appropriate rations that meet the nutritional needs of their beef cattle;

- Identify nutritional gaps that may require supplementation;

- Economize feeding, and possibly make use of opportunities to include diverse ingredients;

- Accurately price feed for buying or selling.

- Use a forage probe for sample collection.

- Obtain cores from 20 bales for each sample you wish to submit.

- Sample square and round bales 12-15″ deep.

- Round bales should be sampled from the rounded sides.

- Square bales should be sampled from the end.

- Combine sample cores, mix and seal in a clean, plastic bag.

- Stoe in a cool, dry location until shipping.

- Take hand grab samples from a minimum of 10 different locations around the stack/pile

- Sample stacks or chopped hay 18” deep

- Collect approximately 2 gallons of ground forage

- Place samples in a clean container and mix thoroughly

- Collect a subsample and seal in a clean, plastic bag

- Store in a cool, dry location until shipped

- Taking hand grab samples from the face is not recommended when sampling silage from a bunker, due to potential safety concerns.

- Using either a loader bucket or face shaver, carefully scrape across the face of the bunker to create a pile of silage on the bunker floor. This can be done at the same time as the day’s feeding to save time on running equipment.

- Collect five to eight hand grab samples from the pile, combine and mix well.

- Take a representative sample and place in a clean, plastic bag.

- Remove air from the bag and store in a freezer or cool place until shipping.

- Avoid old or spoiled silage.

- Collect 8-10 grab samples across the face following a W or M pattern, or 3-5 core samples from along the bag.

- Combine all samples and mix thoroughly.

- Take a representative sample and place in a clean, plastic bag.

- Remove air from the bag and store immediately in a freezer or other cold place until shipping.

- Do not sample from the spoiled material at the top of the silo – remove 2-3 feet prior to sampling.

- From the silage unloader, collect 1 to 2 pounds of silage.

- Mix the silage well and collect a subsample.

- Remove air from the bag and store immediately in a freezer or other cold place until shipping.

- Use a 20L pail with a lid.

- Grab 2-3 small handfuls from every two to three loads.

- Keep the pail lid closed after samples are added to keep in moisture.

- Once the bunker, bag or silo is filled, mix the samples in the pail together and collect a representative subsample.

- Send sample immediately for testing

- Use a forage probe for sample collection

- Obtain cores from 20 bales for each sample you wish to submit

- Tape over the hole after sample collection

- Place core sample in a clean bucket and mix thoroughly

- Transfer mixed core samples in a clean, plastic bag

- Place in a freezer or other cool place until shipping

- Choose a minimum of 8 locations for sampling

- Clip forage from each chosen location within a one square foot area

- Leave 4 inches of stalk

- For plants already in the swaths, collect 3-5 whole plants from 20 locations in the field.

- Carefully cut the forage into 1-to-2-inch pieces and place in a clean, plastic bag

- Store immediately in the freezer or other cool place until shipping.

- Collect 10-15 samples as the product is being unloaded

- Mix the samples together thoroughly

- Place a representative subsample in a clean, plastic bag

- Store in a cool, dry location until shipping

- Use a grain probe

- Collect samples from 10-15 different areas of the bin

- Mix the samples together thoroughly

- Place a representative subsample in a clean, plastic bag

- Store in a cool, dry location until shipping

- Feeding situation (i.e. grazing pastures vs. winter-feeding);

- Plant species;

- Forage management;

- Stage of plant growth;

- Soil type and zone;

- Weather;

- Available stock water and water quality.

- Assess your feed resources. What types of feeds are you planning to use and which tests best suit your forage types?

- Do you have the right tools, including a forage probe? Are the samples you’ve collected representative of your feed types?

- Evaluate your goals for feed testing. What is motivating you? How do you plan to use the results? Have you contacted a nutritionist, agrologist, or veterinarian that you can work with to interpret the analyses?

- Are there potential problems you want to avoid? For example, are you concerned about the risk of mycotoxins in barley, or nitrates in a crop that was stressed? Have you or your neighbors had particular problems in the past?

- Understand the realities of potential results and study your feeding options. If your feed is poor quality or contains potentially dangerous toxins, how can you use it best? Do you have experience using poor quality feed? Do you understand the risks of using potential problem feeds?

- This tool only evaluates the value of the feeds in relation to the reference feeds and the two nutrient components selected. It does not consider other nutrients that affect value or are required for a balanced ration nor does it calculate the actual cost of the feed.

- To ensure all nutrient requirements are met, have a nutritionist do your ration formulation, or use a ration balancing software program.

- For best results, use information from actual feed analysis, not guesstimates.

- For best results, compare feeds that fill similar nutritional needs. Example: while legume hay has high CP% compared to grass hay, it is best valued as a roughage-based source of energy. Feeds like canola meal or distillers grains may be more cost effective sources of CP. They each have a different role to play in the nutrition of cattle.

Feed testing is an important tool when tackling feed management. The following webinars address the key challenges and opportunities surrounding feed testing, what the results mean and why they can be a key tool on your operation.

Download a Feed Sampling Best Practices PDF

Does Your Feed Pass The Test? Making Sense Of Feed Test Results

Video: Feed Testing – Why Do It?

Collecting Feed Samples

It’s critical to collect a feed sample that is representative of the feed ingredient(s) that you are testing. Any feed type that will be used to feed beef cattle can and should be analyzed, including baled forages and straw, by-products, silage, baleage, grain, swath grazing, and cover crops

Feed quality will change as the feeding season progresses. Samples should be taken as close to feeding or selling as possible, while leaving enough time for the results to come back from the lab. Routine re-sampling is recommended to ensure sample results are as accurate as possible throughout the feeding season. If sample results and ration balancing models are not matching, it may be necessary to update samples. It is recommended to provide a minimum 2-week timeframe for sample results after submission.

The equipment necessary for sample collection includes a forage probe, a mixing bucket and sample bags. Some counties, rural municipalities, applied research associations, and forage testing labs also have probes for rent. Forage probes can be purchased from farm supply stores and range in price from about $100 to upwards of $500 for drill driven models.

For all samples, clearly label sample bags with your name, the type of feed, the lot/area where the sample was collected, the date, and any notes that might affect the results.

Video: Feed Testing – Considerations for How to Do It?

Below are recommendations for best practices when collecting samples for varying feed sources:

Click to view Feed Samples PDF

Dry, baled forages

Prior to sample collection, it is recommended to separate your forage inventory into groups with similar characteristics – for example, the same field, same maturity at cutting, and same plant composition. This will allow producers to allocate feed appropriately based on quality and beef cattle requirements.

Sampling with a forage probe is recommended as hand grab samples will not be representative enough to give accurate results.

Sampling recommendations for dry, baled forage:

Where Do I Send Samples?

Feed samples can be sent to labs across Canada and the United States. A listing of Canadian labs can be found HERE. Labs should be chosen on suitability of measurements (NIR vs wet chemistry) for the nutrients you’re interested in and be willing to provide details on how each test/calculation is performed. Standard testing packages from commercial labs cost between $18-200 depending on the suite of tests being performed but can be as high as $450-$500 for specialty analyses.Sampling recommendations for chopped dry forage

Silage

The same general principles for collecting dry forage samples apply for collecting silage samples. There are different recommendations for sampling silage depending on the type of storage system utilized. If the silage pit or bunker is open, one can collect hand grab samples across the face. If a bunker or bag has not yet been opened, a forage probe can be used to collect samples along the top or sides. Remember to reseal any areas that have been cut open to collect a sample to prevent spoilage.

It is important to wait a minimum of 4 weeks after ensiling before sampling. This should be adequate time for the fermentation process to be stabilized.

Sampling recommendations for silage stored in a bunker silo:

Sampling recommendations for silage stored in a bag:

Sampling recommendations for silage stored in an upright silo:

Sampling recommendations for fresh silage:

Click to view Feed Samples PDF

It is important to immediately store silage samples in a freezer or other cool place to prevent spoilage. Ideally, samples should be kept frozen and shipped overnight with an ice pack. However, if the silage is of an ideal moisture content and well-sealed with maximum oxygen removal from the bag, it should be able to store for up to 2 days. It is also best to send the sample early in the week to prevent any weekend delays with the sample sitting in a warehouse.

Bale silage (baleage or haylage)

Bale silage, also known as haylage or baleage, is made by baling high moisture forage using either a conventional round baler or mid-sized square baler and enclosing bales in plastic to exclude oxygen and allow for fermentation to occur.

Sampling recommendations for bale silage:

Swatch grazing and standing crop

For standing crops that are intended to be grazed or swath grazed, producers can collect clip samples from the field. It is important to cut the stems at a height that cattle are likely to eat. A general recommendation is to leave the bottom 4 inches of stalk. Ensure samples are collected from representative areas of the field taking into account high spots, low spots, wet spots, or fence lines.

Sampling recommendations for standing crop and swaths:

Grains, pellets, by-products and alternative feeds

Grains and by-product feeds that are going to be fed to beef cattle should be tested prior to or at receiving. It is recommended to collect the sample during unloading whenever possible.

The nutritional composition of certain by-products can be extremely variable from load to load or between suppliers. In some cases, the moisture content will also vary for certain by-product feeds. Due to this inconsistency, it is recommended to sample each load being received and send for analysis.

Sampling recommendations for grains, pellets and by-products during unloading:

Sampling recommendations for grains, pellets, and by-products in a bin:

What Should I Test For?

This can depend on the types of feeds being tested, the management decisions you need to make, and how much you are willing to spend. Generally, hay and greenfeed analyses should include dry matter, crude protein, acid and neutral detergent fibre, calcium, phosphorus, potassium and magnesium. Silage tests should also include pH; if the pH is less than 5, it has been properly fermented.

Forage that is baled or ensiled when it is too wet can undergo heating and become brown to black in colour with a sweet, tobacco-like smell. This means that some of the protein in the forage will become unavailable to the animal. If heat damage is suspected, analysis of acid detergent insoluble nitrogen or protein (ADIN or ADIP) should be requested. Heating can also produce nitrites, which are ten times more toxic than nitrates.

Some by-product feeds (such as distillers’ grains) or annual forages (such as canola or mustard) may have high levels of sulphates. This can cause polio in cattle. Other considerations include nitrates and mycotoxins.

Near Infrared Reflectance Spectroscopy (NIRS)

It is important to understand the benefits and limitations of testing methods. NIRS uses different wavelengths of light to interpret the kind and amount of organic nutrients present in a sample. The calibration values for NIRS are based on wet chemistry (the gold standard for forage analysis), but it is important to make sure that the lab is using NIRS equations that are appropriate for the samples being tested. For example, a different calibration equation should be used for canola straw versus mixed-grass hay and for fresh or dried sample types. Mineral calibrations are based on an indirect relationship between minerals and organic molecules in the sample, ignoring any inorganic sources, which can lead to higher error rates when NIRS is used for mineral analyses. NIRS is generally faster and cheaper than wet chemistry, but wet chemistry may give a more accurate result for some analyses (particularly minerals).

How to Interpret Results

A Tool for Evaluating Feed Test Results

This tool evaluates the ability of a single feed to meet basic nutritional requirements of different classes of cattle in different stages of production under normal circumstances. It is not intended for use in ration balancing, but rather to alert you to potential issues with individual feed ingredients. These results will not apply if cows are in poor condition, if the weather is extremely cold, wet, or windy, nor does it account for the extra energy expenditure associated with swath grazing. It is strongly recommended that the user seek advice from a qualified professional or use CowBytes Ration Balancing Software to develop a balanced ration for all classes of cattle or for evaluating ingredients when backgrounding calves and developing heifers.

Step 1: Select Cattle Class options are First Calf Heifers, Mature Cows, and Mature Bulls

Step 2: Select Stage of Production (for First Calf Heifers, Mature Cows, Mature Bulls)

Step 3: Enter weight of cattle in lbs in the BLUE cell in Row 20 – acceptable ranges for First Calf Heifers are 850 to 1400 lbs, for Mature Cows are between 1100 and 1600 lbs, for Mature Bulls are between 1800 and 2500 lbs; mid-ranges will round down, e.g

Step 4: Enter your own feed test results on a dry matter basis, starting with Dry Matter (DM,%). Click Calculate Single Feed Data to return your results.

Interpretation:

Suitability of the feed is indicated by a color coded response. Green indicates that the nutrient is adequate to meet nutritional requirements. Yellow is within +/- 2.5% of TDN requirements, +/- 5% of CP reqiurements and 0.05% below mineral requirements.. Red indicates the feed does not meet animal requirements.

The indicator colors are linked to the nutritional requirements of a specific animal type and stage of production. If the animal type or stage of production is altered, the colors indicating suitability for use can change. For example: nutritional requirements for a cow in late pregnancy are substantially higher than that of a cow in early gestation. A feed that is not adequate for one group may be satisfactory for a different animal type.

* Calculations are based upon generally accepted nutrition “rules of thumb” derived from CowBytes, the National Research Council’s Nutrient Requirements for Beef Cattle, & Alberta Agriculture and Forestry

Feed quality differs according to forage species, stage of maturity at time of harvesting, weathering of forages, storage conditions, plant disease, and other factors. It is important to not rely on averages and to test feeds annually. Forage quality can vary significantly within a field and year to year.

Meeting Nutrient Requirements for Cattle

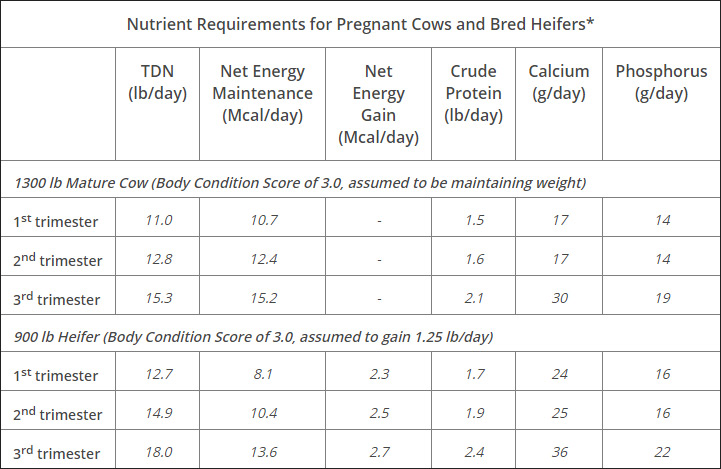

The main reason producers should test their feed is to ensure they are meeting the nutritional needs of their livestock. Nutritional needs vary greatly depending on stage and age of cattle and whether you are growing, finishing, breeding, or maintaining cattle. Body condition score, hide thickness, and hair coat can affect nutrient requirements of cattle, as can weather conditions like precipitation, temperature and wind speed, or environmental factors such as mud depth, bunk space, or other factors. An example of nutrient requirements for cows compared to bred heifers is in the following table. A common rule of thumb is 55-60-65 and 7-9-11 for the percentages of TDN and CP, respectively, required by a beef cow in early-, mid-, and late-gestation.

* Values are from www.BeefResearch.ca and were generated using the ration-balancing software program CowBytes, with assumptions including breeding for June 1 calving, typical Canadian winters, access to shelter from wind and a daily gain of 1.25 pounds for bred heifers in addition to weight gain from pregnancy.

Interpreting Lab Results

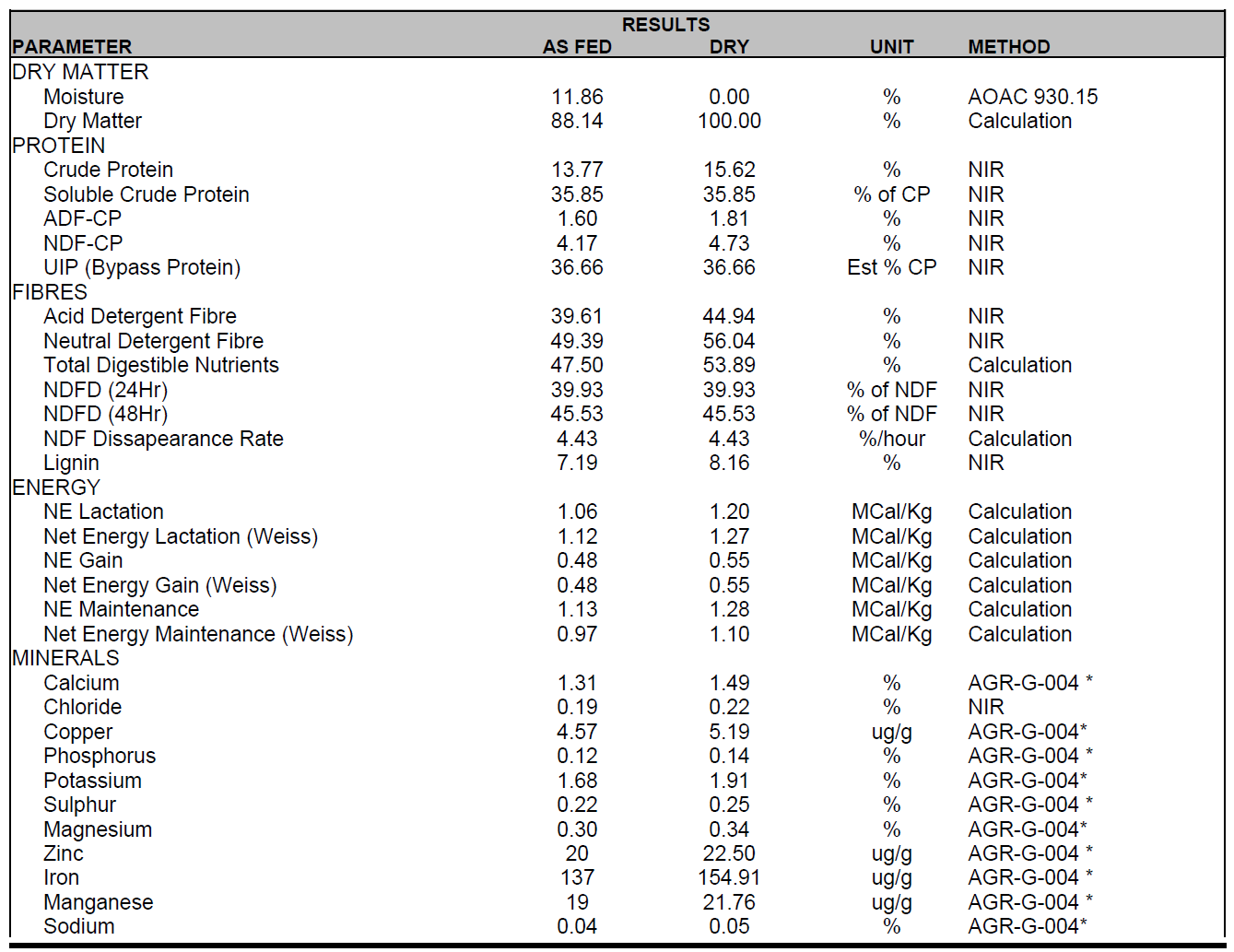

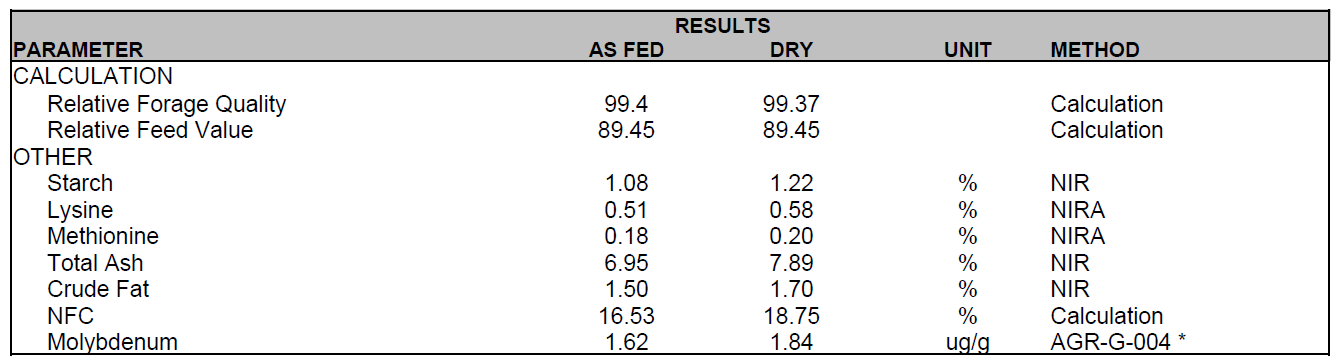

Most labs provide basic information on moisture content, protein, energy, total digestible nutrients, fibre, and some vitamins and minerals. More specialized tests may include results for pH, ADIN, nitrates, toxins, relative feed value (RFV), and other parameters.Below is an example of feed test analysis results for a grass-alfalfa mix hay:

Example lab results for a grass-alfalfa mixed dry hay.

Dry Matter (DM, %) refers to the moisture-free content of the feed sample. The water content of forage will dilute nutrients. Therefore, it’s important to balance all rations on a dry matter basis. The daily intake of mature beef cattle will be 1.75%-2.5% of body weight on a dry matter basis. Moisture contents outside of expected ranges can indicate potential spoilage issues. The average dry matter of hay is 85-90%, meaning on average hay contains 10-15% water. For silage, average dry matter is 30-45%, meaning in an average year, silage contains 55-70% moisture. This may be less if silage is harvested in drier conditions. Grain has an average dry matter of 90%, meaning up to 10% may be water. The example above shows a dry matter content of 88%, which is within the ideal range for dry hay.

Ash (%) is the inorganic (mineral) component found within plants and is inversely related to energy. In a forage sample, ash can also come from external sources such as soil or bedding. Excessive ash content (>5% for corn silage, >8% for alfalfa, >6% for grasses and >10% for legumes) can indicate external contamination in the sample. The results above show an ash content of 7.89% for a grass-alfalfa mix hay. Although this level is not excessively high it does indicate possible soil contamination.

Crude Protein (CP, %) is an estimate of the total protein content of a feed determined by analyzing the nitrogen content of the feed and multiplying the result by 6.25. Crude protein includes true protein and non-protein nitrogen sources such as ammonia, amino acids and nitrates. Protein digestibility can vary, and proteins may be bound to indigestible forms (i.e. heat damaged proteins).

Neutral Detergent Fibre (NDF, %) is a measure of the insoluble fibre content in the plant, which includes the plant cell wall components.

“High levels of NDF (above 70%) result in lower digestibility and reduced voluntary intakes. ”

More mature forages will have higher NDF levels. The NDF level of 56% is adequate in the above example.

Acid Detergent Fibre (ADF, %) measures the least digestible portions of the plant (i.e. cellulose and lignin) and is negatively correlated with total digestibility. High quality legumes will typically have ADF values between 20-35%, while grasses can range from 30-45%. In the above example, the ADF value of 44.94% is on the high side for a grass-alfalfa forage, meaning there is potential for reduced digestibility.

Acid Detergent Insoluble Nitrogen (ADIN, % of total protein) also referred to as acid detergent insoluble protein, acid detergent insoluble crude protein, acid detergent fibre protein, insoluble protein or bound protein, is a measure of heat damage during harvest and storage that can bind protein and make it unavailable to cattle. A level of 3-8% ADIN can be present in feeds with the complete absence of heating. The above example has a very low reported ADF-CP level of 1.81%, indicating that no heat damage is present.

Total Digestible Nutrients (TDN, %) is defined as digestible carbohydrate + digestible protein + (digestible fat x 2.25), reflecting the greater caloric density of fat. A TDN value can be converted into estimates of digestible, metabolizable, or net energy. It’s most useful and accurate for rations comprised primarily of plant-based forages.

Net Energy (NE) is a measure of the energy available to the animal for maintenance and productive purposes (growth, gestation and lactation). The NE requirements for maintenance, growth and lactation are denoted by NEm, NEg, and NEl, respectively.

Non-Fibrous Carbohydrates (NFC) represent the soluble components of the plant stored in the cell wall (starch, sugar, soluble fibre, organic acids) and provide energy to the animal. The microbial population within the rumen breaks down the NFCs for use as an energy source. NFC levels will be lower when ADF and NDF portions are higher. Alfalfa hay averages and NFC level around 30%, while grass hay is around 19%. The sample above has an NFC value of 18.75%, which is close to average for grass hay and indicates a good-quality forage.

Relative Feed Value (RFV) is an index that estimates intake and digestibility and is useful for evaluating 100% alfalfa hay or silage only, with full bloom alfalfa hay used as the baseline with a RFV of 100. Values below 80 normally will not meet animal requirements for energy. It is not reliable for mixed hay, grass hay or cereal greenfeed. It is often used for price discovery but is not helpful when balancing rations.

Relative Forage Quality (RFQ) is an index that estimates intake and TDN. The estimate of intake is based on different equations for grasses versus legumes or legume-grass blends and includes additional factors to improve the accuracy of prediction, as well as in vitro measures of NDF digestibility. RFQ can be used for legume, grass, and legume/grass mixtures. The RFQ value for full bloom alfalfa hay will be similar to the RFV, but when samples differ in NDF digestibility, RFQ will differ from RFV.

Many feed analysis reports will include calculations of digestible energy, metabolizable energy, net energy for gain, net energy for lactation, and net energy for maintenance. Differences in the way these are calculated may exist between labs. You can input your forage results into the calculator at the top of the page to see if it is suitable to feed to cattle as is or if you will need to blend with other feed.

Preventing Problems

One of the major benefits of feed testing is preventing costly and devastating problems before they start. Every season is different and some years there is an abundance of high quality forage. Other years, there is a lack of available feed, or perhaps there is an abundance of low quality forage, grain, or grain by-products available that may look economical but can potentially pose significant risks if a feed analysis has not been performed or understood.

Moulds & Toxins

Mould can occur in forages, grains, clover, corn, and by-products or derivatives of those feed ingredients. Moulds occur due to plant diseases such as ergot, fusarium head blight, Aspergillus, and many others. The incidence of these plant diseases increases during cool and wet growing conditions, or in crops left standing throughout the winter. Mould will reduce the energy content and palatability of feed. Mouldy feed can also cause production problems including abortions and respiratory disease and can cause the development of mycotoxins in feed. Mycotoxins such as ergot alkaloids, vomitoxin, and aflatoxin can lead to reproductive failure, reduced milk production, depressed gains, convulsions, gangrenous symptoms (i.e. sloughing of hooves, ears or tail), and death.

Avoiding moulds in feed isn’t always possible, so it’s important to test feed to determine how much and what type of mould may be present so producers can realistically deal with the situation. Avoid feeding mouldy feed to young or pregnant animals, and obtain guidance from a nutritionist about safe ways to blend potentially problematic feed to dilute the contaminants. Prairie Diagnostic Services Inc. has a helpful mycotoxin calculator available online to assist producers with determining their risk level.

Access the calculator online HERE.

Mineral Nutrition

Mineral nutrition as provided by forages depends on:

Trace minerals, particularly copper, zinc, and manganese, are important for the reproduction, health, and growth of an animal, and almost always require supplementation. Other minerals, such as molybdenum and sulfur, have antagonistic properties that work against an animals’ ability to absorb these minerals. Stock water that contains high levels of sulphates, or forages that contain high levels of sulfur, such as Brassicas (i.e. canola, radish, turnip), can interfere with copper absorption and cause deficiencies. Soils and/or forages high in molybdenum can also lead to copper deficiencies, so producers must consider all sources of minerals when consulting on their supplementation needs.

In most cases, it is recommended minerals must be supplemented year-round. Producers should work with a nutritionist to ensure they understand how their mineral supplementation program works, and that they are meeting the needs of their cattle depending on the stage of breeding or gestation. It’s also critical to determine whether the products they are purchasing are being consumed (and minerals are being absorbed) at appropriate levels, by all cattle.

Nitrates

Annual crops such as oats, barley, corn, or millet can accumulate nitrates under certain growing conditions, including severe drought, hail storms, or frost. Cattle can metabolize a certain level of nitrates, but if the diet contains more than approximately 0.5% nitrate (NO3) on a DM basis subclinical toxicity can occur causing reductions in weight gain, decreased feed intake and milk production, and an increased risk of infections. Diets containing more than 1% NO3 may result in death loss and abortion. Mature cows and

First Calf Heifers

are most at risk and can have symptoms such as abortions, premature calves, newborn calf mortality, poor growth and reduced milk production.

A simple and cost-effective feed test can rule out potential problems due to nitrates. Depending on the level of toxicity, the feed may be blended off to dilute the nitrates to safe levels.

What About Water?

Feed testing is critical, but beef cattle also obtain nutrients from water. Producers must consider regularly sampling stock water to prevent nutritional problems. In many cases, forage alone or water alone may not cause toxicities in beef cattle, however when the two are combined, the cumulative effects may lead to problems. This may be particularly true for sulphates or nitrates and can occur in either grazing or winter feeding situations.

Testing stock water quality may be particularly important during a drought, when minerals and nutrients may become concentrated as water tables drop in surface or ground water, or evaporation occurs in stock ponds.

For more information on water testing, quality and systems go to: /topics/water-systems-for-beef-cattle

Formulating Rations

Once feed test results are available, producers can formulate an appropriate ration for their cattle using the services of a qualified nutritionist, the assistance of agriculture extension staff, or through a software program such as CowBytes (Version 5). CowBytes is currently available for purchase through the BCRC. There are also several free, useful online tutorials available.

Different rations need to be developed for as many separate classes of cattle as necessary. Producers may choose to group their herd according to needs. For example, a breeding herd may be split into one group of mature cows that have a good body condition score and simply require maintenance, and another group of older or thin cows that need to gain weight.

Minerals and salt most often need to be supplemented during the winter feeding period according to feed results. For rations comprised mainly of alfalfa, grass, or a mix of the two, calcium and phosphorus typically needs to be supplemented in a 1:1 mix. For rations that contain more cereal-based forages, including pellets, straw, or greenfeed, supplementation of a 2:1 or 3:1 mix may be required. Animal needs will also change as they move through gestation and lactation.

Interested in feed testing? What’s next?

A Tool for Evaluating the Economic Value of Feeds Based on Nutrient Content

This tool will help to determine the value of feeds that you may be considering to purchase as compared to the feed value of two standard feeds (barley and canola meal are the current examples, but can be changed) using current market prices.

Step 1: Enter the current feed price ($/tonne, As Fed) for the reference feeds (e.g. barley grain, canola meal) in corresponding cells.

Step 2: For each feed you are considering enter the required information in the Target Feeds table.

Step 3: Have a nutritionist do a proper ration to ensure all nutritional requirements are met.

Step 4: Determine your best feed strategy.

How do you know if the feed you are considering to purchase is the best deal for you?

When looking to purchase feed and you have multiple sources to consider, being able to calculate the nutrient value of each feed as they compare to a reference source, is the way to go. A simple tool has been developed to help you do just that.

How the tool works:

The basics:

Reference feeds

The tool uses barley grain and canola meal as the two reference feeds to start, however you are able to change these to the reference feeds that best suit your needs. The current cost free on board the farm (i.e. the cost delivered into the yard) and the respective nutrient content of these feeds, form the basis to calculate the nutrient value for the feeds that are considered for purchase.

Target Feeds

The information for the different target feeds (price, dry matter (DM) percentage, total digestible nutrients (TDN) and crude protein (CP) on a dry matter basis) need to be entered in the green cells in the Target Feeds table. To make best use of this calculator, use feed test data and pricing for your area.

Results

The results are calculated in the last three columns of the Target Feeds table.

The calculated nutrient value ($/tonne) is the estimated “economic” value of the feed. This is based on its nutrient content (from the sample values) and the values of the nutrients as calculated from the reference feeds. The higher the value, the higher the cumulative content of TDN and CP of the targeted feed, and thus the higher the feed value.

The second part provides a number value. Even though it is expressed as a $/tonne it cannot directly be translated to feed cost as we are not talking about a ration and other components will need to be included to ensure a balanced ration. What the numbers can be used for is to see which feed has the best potential to be used in the final formulation of a ration. It provides a simple ordering of the feeds (based on limited nutrient information), where the highest value represents best option to consider from a cost perspective. If all values are negative that does not mean you should not consider these feeds for purchase. What it does mean is that the feed with the lowest negative value may be the best economic option for you to consider while building a ration and using that feed will likely result in the lowest increase in overall feed cost.

Additional tips for using the tool:

The tool is set up with barley grain and canola meal as the standard reference feeds. If you use different feeds, or have feeds with different nutrient levels, you can change the reference feeds to reflect your personal situation. As a result, the information calculated in the Target Feeds table will be more reflective of your own situation.

The table is set up so you can also change TDN and CP components, and use different nutrients if there is a need for it. For instance, if the feed is only going to be used to meet the maintenance requirements of the cattle (i.e. early gestation non-lactating cows, or mature bulls) using the net energy for maintenance (NEm) available from feed test results should give a more relevant estimation of feed value.

Disclaimers:

The impact on feed cost is divided into two parts. The first part is the column indicating Negative or Positive. If the Asking Price is lower than the Calculated Nutrient Value, a “Positive” will occur in the first column. If that is the case, then you can consider this feed a good deal based on its nutrient composition.

This page was developed by the Alberta Beef Forage and Grazing Centre

Special thanks to: Dr. Hushton Block (AAFC), Barry Yaremcio (AAF), Herman Simons (AAF), Jennifer Schmid (Excel Wizard)

Feedback

Feedback and questions on the content of this page are welcome. Please e-mail us at info@beefresearch.ca.

Expert Review

This content was last reviewed March 2024.