Effective grazing management on pastures not only ensures high forage yield, sustainability, animal health and productivity, all of which impact cost of production, it also benefits the pasture ecosystem. Pasture management gives producers greater control to support the environment (e.g. biodiversity) but also allows them to better use pasture resources for food production.

Pasture is a critical resource in the cattle industry. An effective management plan requires clear understanding of forage production, realistic production goals, effective grazing strategies and timely response to forage availability and environmental changes. Managing grazing lands so that they are productive and persist over time requires knowing when to graze certain species, if they can withstand multiple grazings/cuttings within a single year and how much recovery time is needed to prevent overgrazing (which is a matter of time not intensity).

| Key Points |

|---|

| Plant Growth |

| – The timing of the “S” shaped growth curve for each forage species is unique and an important factor in determining proper season of use for grazing e.g. keeping plants in phase II |

| Rest and Recovery |

| – Overgrazing is a function of time; rest is key to prevent overgrazing with slow growing plants requiring more rest time than fast growing ones |

| Stand Management |

| – Plant diversity is important to maintain a productive pasture. Maintain diversity and productivity by using the “Take Half, Leave Half” principle. |

| Developing a Grazing Plan |

| – A grazing plan that matches animal numbers to predicted forage yields should be carried out before animal turnout |

| Paddock Design |

| – The size and shape of your paddock will be dependent on topography, soil, plant species, plant yield, herd size, preferred stock density and water source |

| Livestock Distribution |

| – Livestock do not graze randomly and must be forced or enticed to seldom used areas – one way to encourage this is through fencing and placing salt and mineral away from water sources. |

| Grazing Legumes |

| – Including legumes as part of an annual grazing plan can help restore soil nitrogen, increase forage yields and extend pasture carrying capacity |

Plant Growth

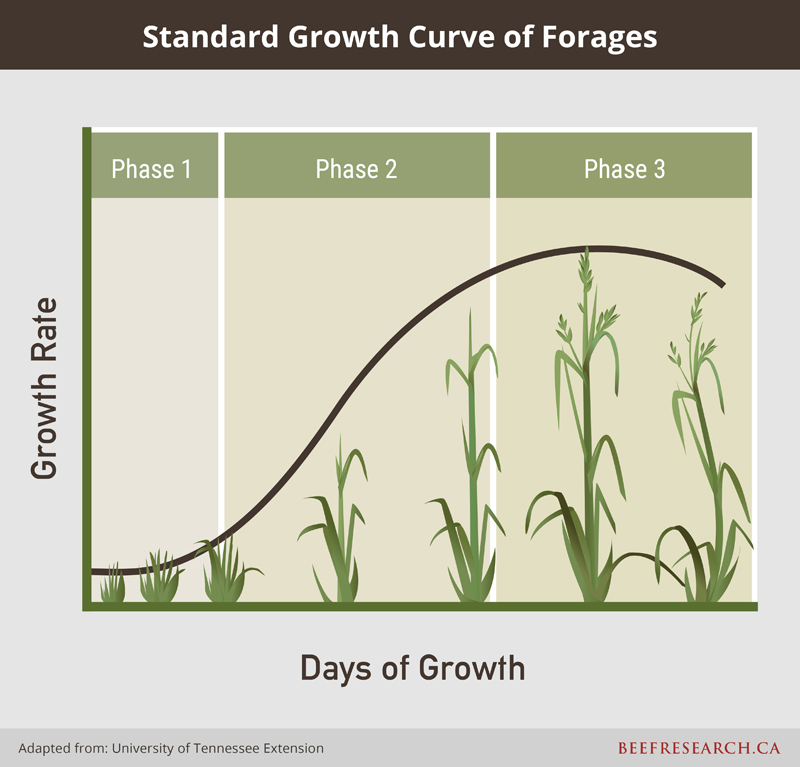

The efficiency with which plants convert the sun’s energy into green leaves and the ability of animals to harvest and use energy from those leaves depends on the phase of growth of the plants. Plants go through three phases of growth that form an “S” shaped curve (Figure 1).

Phase I occurs in the spring following dormancy or after severe grazing where few leaves remain to intercept sunlight forcing plants to mobilize energy from the roots. The roots become smaller and weaker as energy is used to grow new leaves.

Phase II is the period of most rapid growth. When regrowth reaches one fourth to one third of the plant’s mature size, enough energy is captured through photosynthesis to support growth and begin replenishing the roots.

Phase III material is mature and nutrient content, palatability, and digestibility is relatively poor. Leaves become shaded, die and decompose. During this phase new leaf growth is offset by the death of older leaves.

Adjust grazing and rest periods to keep plants in Phase II. Do not graze plants so short that they enter phase I as regrowth is very slow. Nor should plants be permitted to mature and enter phase III as shading and leaf senescence reduces photosynthesis and overall plant biomass. The harvest of energy is maximized by keeping plants in phase II.

Figure 1: The sigmoid (S) growth curve of a typical forage stand indicates how yield, growth rates and rest periods change over the growing season. (Voisin 1988).

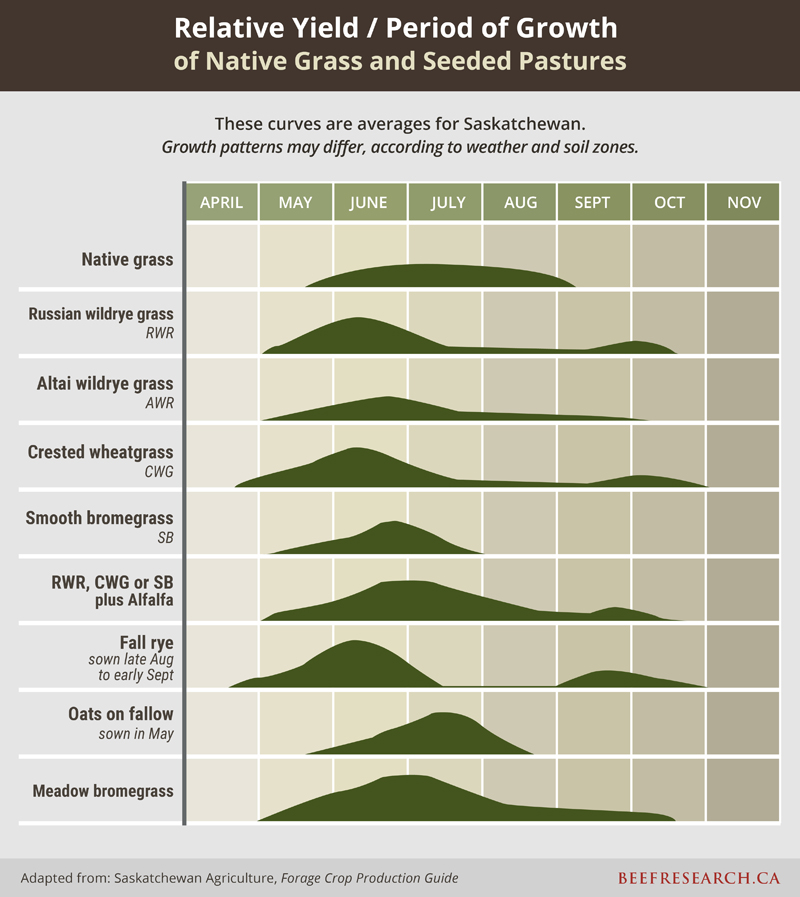

The timing of the growth curve for each forage species is unique and these growth characteristics are an important factor in determining proper season of use for grazing (Figure 2). For example, crested wheatgrass begins growth relatively early in the growing season while native grass species grow later in the season. Based on these characteristics, crested wheatgrass is best grazed early in the season with native rangelands better suited for use in the summer or fall. It is important to recognize that forage species may be grazed outside their optimal season of use however, the subsequent rest period must be extended to allow plants adequate time to recover.

Figure 2 – Average relative yield and period of growth of native grass and seeded pastures in Saskatchewan.

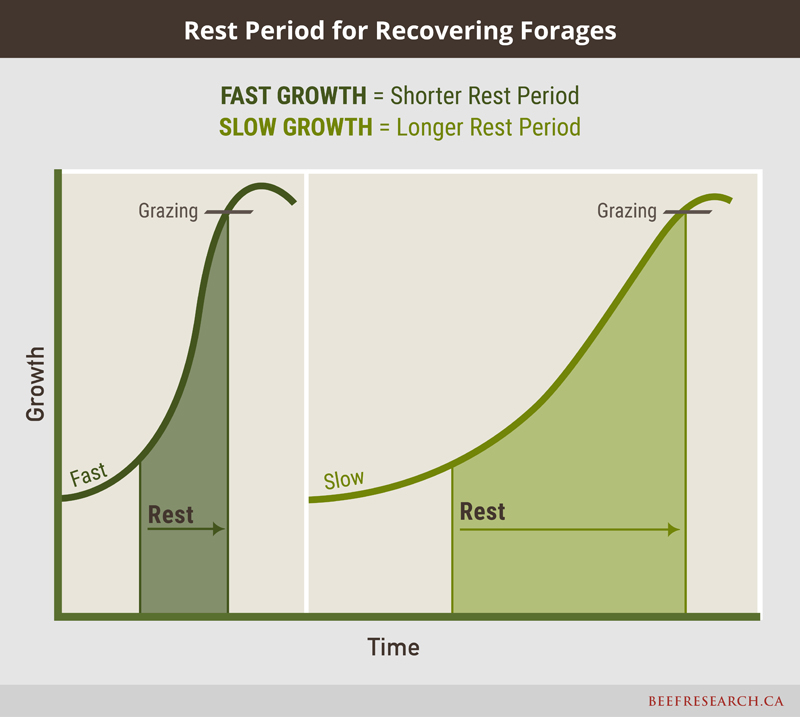

Rest and Recovery

Overgrazing is a function of time and occurs when a plant is grazed (defoliated) before it has recovered from a previous grazing event. This occurs by either leaving grazing animals in a paddock too long or bringing them back too soon, before plants have had a chance to recover and regrow. Rest is key to prevent overgrazing and must occur when the plants are actively growing, not during dormancy.

The length of time that a plant needs to recover following grazing depends on several factors including the type of forage species, plant vigour, and the level of utilization (i.e., how much plant material has been removed). Recovery time also depends on the season or time of year which determines conditions such as daylength and temperature. Fertility and moisture also impact plant growth rates.

When plants are growing slowly, such as in drought or late summer, the required recovery or rest period will need to be longer than when plants are growing rapidly. This relates to the “S” shaped growth curve discussed above. Understanding the phase of the growth curve, the corresponding rate of growth, and the timing of the growth period for each forage species, is critical to management decisions related to adequate rest and recovery periods.

Figure 3: the required recovery or rest period will need to be longer than when plants are growing rapidly

Determining the number of days of rest required is unfortunately, not a simple calculation. Rather, watching and evaluating how pastures regrow and recover will provide the best information. With experience will come the knowledge needed to determine when a pasture has recovered and is ready for grazing. As a general rule, a minimum recovery period is estimated to be at least 6 weeks.

Stand Management

Maintaining a pasture stand in good condition is critical to a successful grazing plan. Desirable species provide high quality forage and production for a large part of the grazing season. Typically, the desirable forages are hardy grasses and legumes that regrow quickly. Undesirable species are those that are typically unpalatable to the grazing animal or may contain anti-nutritional components. Plant diversity is also important to maintain a productive pasture throughout the entire landscape and growing season. If only one kind of plant exists, diversity is narrow, and production will be limited. If many plant varieties are present, diversity is broad. High plant density must also be maintained as bare and open spots are unproductive and allow for weed encroachment and soil erosion.

Management of a forage stand relies upon the level of utilization that allows for maximum grazing of forage without damage or negative impact to the vegetation, including both above and below ground growth. Determining the optimum amount of forage to remove versus leave behind is not an easy task and depends upon plant, animal, and environmental factors. Research findings and professional judgement help provide guidelines for determining appropriate level of utilization, but experience is the best guide. A general guideline often employed by grazing mangers employs the ‘take half, leave half’ rule or 50% utilization by weight (biomass) of the key available forage species in a stand. This level of utilization fits a moderate level of grazing intensity and is a good starting guideline to employ. However, it is important to adjust utilization rates based upon site-specific variables including forage species, time of year, available forage, and overall management goals.

The overall condition of a forage stand impacts the number of animals that a pasture can support and the length of time that grazing can occur. Factors such as previous grazing management, species of forage, age of stand, soil type, texture, fertility level and moisture conditions all influence forage yield and quality and consequently stocking rate. Understanding these factors and implementing a grazing system is key to effective grazing management.

An interactive Forage Species Selection Tool is available to assist land managers in selecting the correct forage species best suited their land. Seeding rate and seed cost calculators are integrated as well.

Visit the Rangeland and Riparian Health page for more information, including videos, related to pasture condition and health assessments.

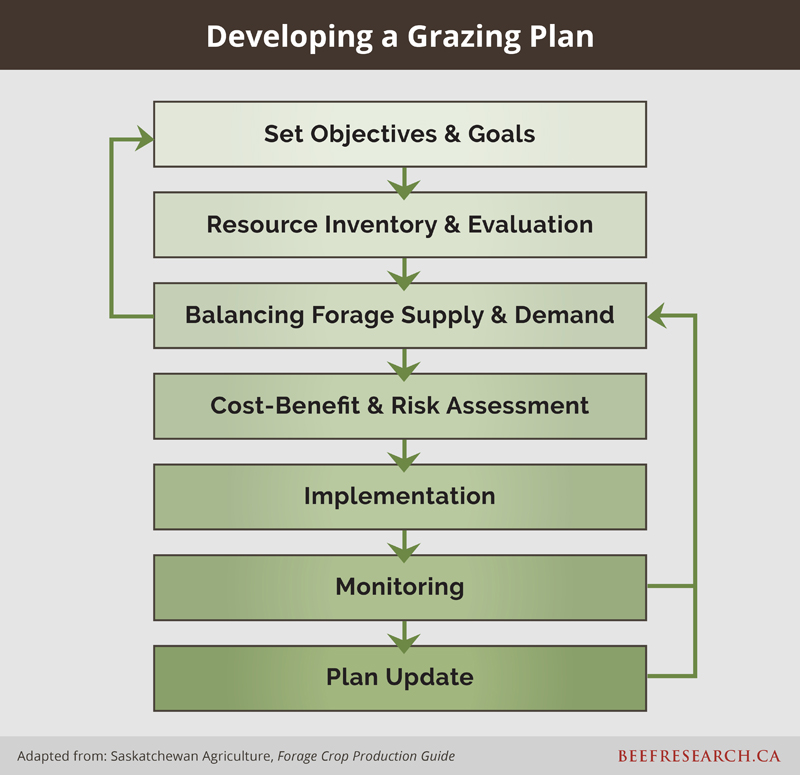

Developing a Grazing Plan

A grazing plan that matches animal numbers to predicted forage yields should be carried out before animal turnout.

An important first step in developing a plan includes defining goals and objectives for the entire grazing operation. This includes profitability measures, lifestyle choices, and biological outcomes such as soil health, forage production, ecosystem impacts and animal performance.

Conducting an inventory of resources is essential. How much forage is available and at what times during the grazing season? Is the forage source able to meet the intended animals’ nutritional requirements? How long is the intended grazing season? What physical infrastructure is available or needed?

This process of completing an inventory and evaluating resources is critical to developing and implementing a successful grazing system. The Pasture Planner: A Guide to Developing Your Grazing System provides an excellent resource to assist producers with planning, development and/or modification of their grazing system. It includes a number of worksheets and templates useful in the inventory and planning process.

Previous webinar:

Grazing Systems

A grazing system is the way a producer manages forage resources to feed animals, balancing livestock demand (both quantity and quality) with forage availability and promoting rapid pasture re-growth during the grazing season as well as long-term pasture persistence. Grazing systems will vary with the climate, plant species, soil types and livestock. Systems that are commonly used in Canada include continuous grazing or controlled grazing systems which are numerous and varied, even in their terminology, including but not limited to: rotational grazing, forward grazing, creep grazing, strip grazing, limit grazing, stockpile grazing and extended grazing.

A number of resources exist which provide an excellent overview of the types, development, and implementation of grazing systems. Examples include:

Pasture 101: Managing and Planning Grazing

Maritime Pasture Manual: Chapter 2 – Grazing Systems

Managing Saskatchewan Rangeland

Pasture Planner: A Guide for Developing Your Grazing System

With continuous grazing, animals will naturally graze the most palatable plant species most frequently. Root reserves are eventually exhausted, and plants may die. In highly stocked continuously grazed pastures, regrowth will be grazed quite frequently. Lightly stocked continuously grazed pastures consist of patches of plants in phase I and phase III. If animals are forced to eat phase III material, their daily intake will drop, reducing animal gains.

In a controlled grazing system, animals only have access to relatively small parts of a pasture for a period of time. Pastures are divided into paddocks where the land is grazed for relatively short periods of time following which, livestock are removed to ensure the plants have adequate time to recover before being grazed again. Because this requires more knowledge of forage plants and pasture-animal interactions, controlled grazing is often referred to as management-intensive grazing (MIG).

Whether managing native rangeland or tame forage species, four basic principles of management apply:

- balance the number of animals with available forage supply

- obtain a uniform distribution of animals over the landscape

- alternate periods of grazing and rest to manage and maintain the vegetation

- use the kinds of livestock most suited to the forage supply and the objectives of management.

Stocking rate histories on similar fields in the same area can be very useful in setting initial stocking rates. The optimum number of animals on a pasture makes efficient use of the forage but leaves enough plant material behind to allow a quick and complete recovery.

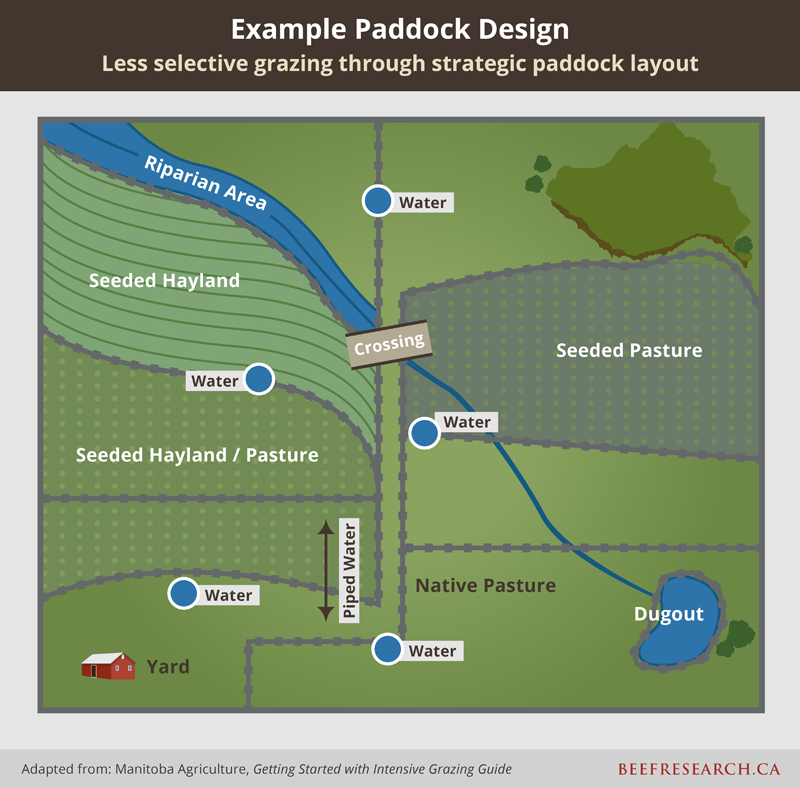

Paddock Design

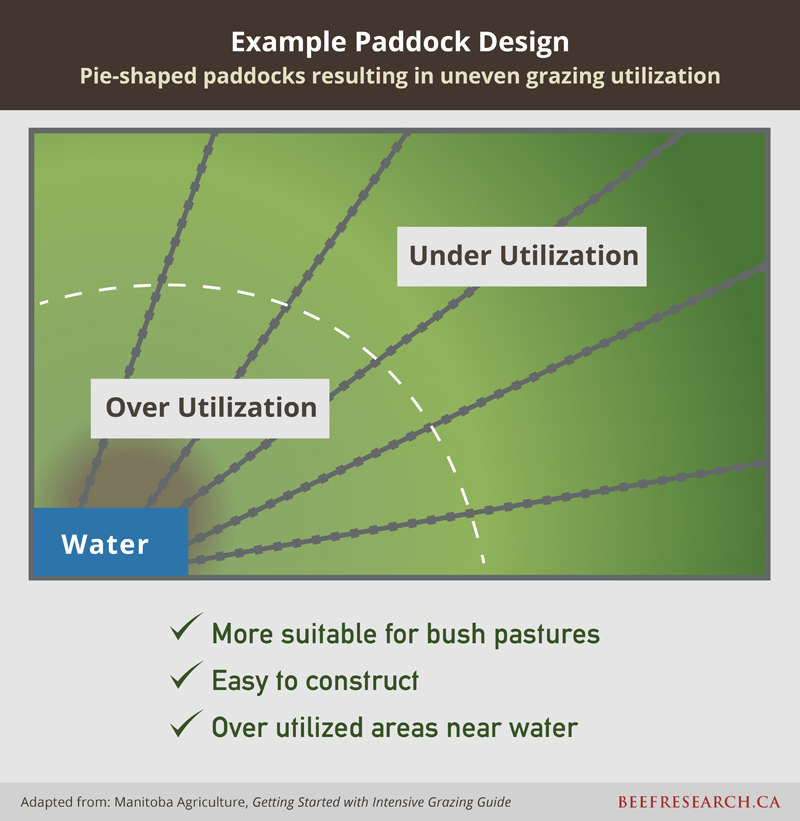

When developing a grazing system, paddock shape should be determined by the topography, soil type, and species differences to reduce problems with uneven grazing and varying recovery time. If a paddock has a lot of variation in it, some areas will be underutilized while others are severely grazed.

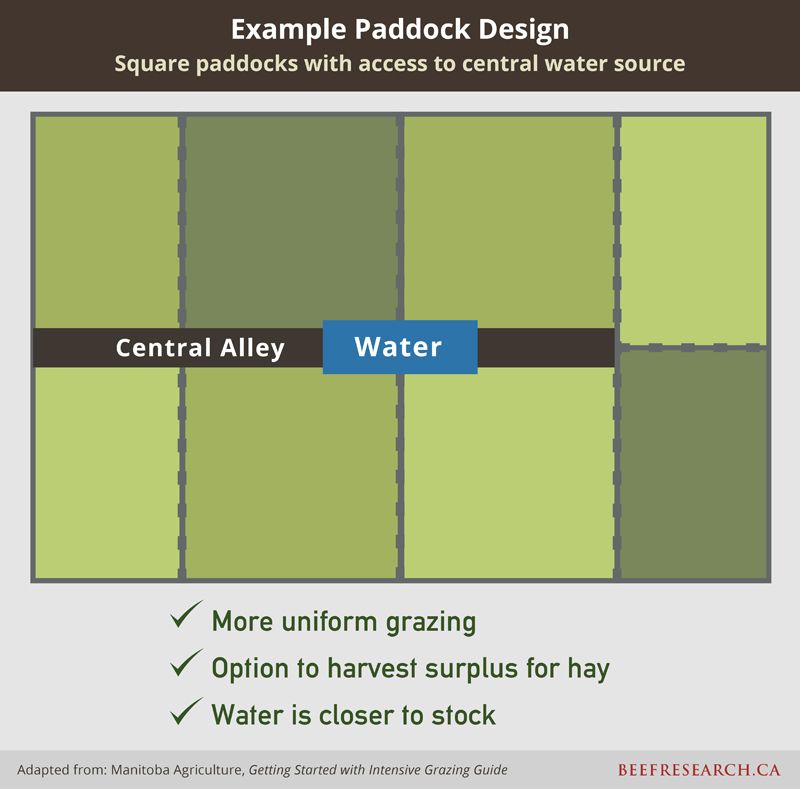

The size of individual paddocks should be determined by the projected herd size based on forage production potential and preferred stock density to keep the frequency of cattle moves consistent. As productivity of the land increases, paddock size should be reduced to achieve desired levels of utilization. Generally, square paddocks offer more uniform forage utilization and better manure distribution compared to long narrow shapes.

Developing a practical water distribution system is an important consideration in designing an efficient grazing plan and paddock design. Access to water impacts grazing patterns of livestock and understanding this will assist in managing forage utilization. It is recommended that pasture systems be designed to provide water sources within 600 to 800 feet of all areas of a paddock for optimum uniformity of grazing2. Portable water systems are a powerful tool for managing grazing distribution and manure cycling. If water cannot be provided in each paddock, laneways designed to bring the stock to the water source are the next alternative. Plan the pasture layout to minimize laneway length and keep laneway width within 16 –24 feet to reduce the amount of loafing by animals3. Similarly, minimizing the common area around a water source will reduce the amount of time that animals spend congregating at the site.

Over 300 insect species are found in cow dung on Canadian pastures; mating, eating dung, laying eggs, eating each other – all while providing valuable ecosystem services.

The Cow Patty Critters guide is a dung detective’s handbook for studying cow dung communities on pastures across Canada. The second part of the Cow Patty Critters guide provides tools and instructions on how to identify dung insects and other critters.

Livestock Distribution

Proper livestock distribution, achieved by spreading grazing animals over a pasture unit to obtain uniform use of all forage resources, can increase production. Grazing distribution varies with the kind and class of grazing animal, topography, location of water, salt and mineral placement, forage palatability, vegetation type, forage quality, forage quantity, location of shade and shelter, fencing patterns, pasture size, grazing system, stock density, and prevailing winds.

Ideal grazing distribution occurs when the entire pasture is grazed uniformly to an appropriate degree within a predetermined time frame. Cattle, being creatures of habit, rarely graze uniformly when left alone. They graze convenient areas, especially those near water and easily accessible. Livestock do not graze randomly and must be forced or enticed to seldom used areas.

Improving grazing distribution results in higher harvest efficiency because livestock consume a greater proportion of the available forage. It also spreads defoliation effects across a greater proportion of available forage plants.

Methods for improving livestock distribution include:

- managing stock density and/or season of grazing;

- forcing animals to specific locations by fencing;

- using grazing management strategies such as rotational grazing;

- enticing animals to specific locations with water, salt, supplemental feed, or rub and oiler placement; and

- using the kind and class of livestock best suited to the terrain and vegetation characteristics.

Placement of water developments is probably the most important factor affecting grazing distribution as water is the central point of grazing activities. Near water, plants are heavily used and forage production drops. Reducing pasture size and reducing the distance to water can significantly improve livestock distribution. Salt and mineral should be placed away from water and used to distribute animals more uniformly.

Topography is an important cause of poor grazing distribution. Where possible, pastures should be fenced to minimize variability in topography, plant communities, and timing of plant growth.

Shade is another important factor of animal distribution as animals will migrate towards these areas during the hot times of the day to stay cool and to avoid insect irritation.

Grazing Legumes

Legumes as part of an annual grazing plan can be advantageous as these plants can help restore soil nitrogen, increase forage yields and extend pasture carrying capacity. Improved animal performance may also be achieved when grazing stands containing legumes. However, legume grazing requires increased management efforts to ensure optimal stand persistence and animal performance.

Producers are often hesitant to seed alfalfa for grazing purposes due to fears of bloat even though yield and productivity could be increased. To gain the benefits of grazing this legume, careful management is critical. To reduce the risk:

- Do not move cattle onto new pasture when it’s wet with heavy dew, rainfall or irrigation water. Grazing alfalfa when it is wet increases the possibility of bloat, so it’s better to move animals to a new pasture in the afternoon rather than in the morning.

- Never allow animals to stand hungry before turning them into an alfalfa pasture, as it can lead to overconsumption of fresh alfalfa.

- Wait until alfalfa is in full bloom to graze. Bloat risk is highest when alfalfa is in vegetative to early bloom stages of growth. As alfalfa enters the full bloom or post bloom stages, soluble protein levels decrease, plant cell walls thicken, lignin content increases, and the rate of digestion of alfalfa in the rumen decreases.

- Do not graze alfalfa for three days to two weeks following a killing frost. Frost may increase the incidence of bloat by rupturing plant cell walls, leading to a high initial rate of digestion. Delay grazing alfalfa until the stand dries. The time required to dehydrate varies by location and weather.

- Make sure to monitor cattle frequently for condition and any signs of bloat or sickness and adjust grazing plans accordingly.

The risk of bloat when grazing pure alfalfa stands can also be reduced through the selection of reduced bloat varieties (e.g. AC Grazeland) and the use of products including Bloat-Guard, the Rumensin CRC bolus, or Alfasure.

Many producers prefer to avoid bloat by seeding alfalfa-grass mixtures. Depending on the percentage of alfalfa in the mix, this can reduce the risk of bloat but maintaining alfalfa within the stand can be a challenge. Over time plants disappear from the stand eliminating many of the benefits including increased fertility.

A study in Swift Current, Saskatchewan4 showed that alfalfa and sainfoin plant counts both dropped by 50% over the four-year grazing trial. Research conducted near Brandon, Manitoba also found that the alfalfa percentage in a mix declined from 75.4 – 84.1% to 32.5 – 40.3% over a four-year period5.

The following management techniques can help to maintain legumes in a stand:

- in the spring, wait until alfalfa is three to four inches tall before grazing. After the spring grazing period ends, allow the alfalfa to regrow for about 25 to 40 days before grazing again or cutting for hay.

- allow plants rest during September and October, or control grazing to maintain at least 6 to 8 inches of standing alfalfa at all times.

- avoid reducing stubble height to less than 2 or 3 inches in late fall to help protect alfalfa from winter damage.

- allow plants to grow without cutting or grazing for at least four to six weeks prior to the first killing frost.

There are many other legume species that in more recent times are seeing increased use within grazed pasture stands. This includes sainfoin, cicer milkvetch, birdsfoot trefoil, alsike clover, red clover, white clover, kura clover, sweet clover, and purple or white prairie clover. These legumes may not have the yields of alfalfa but may better suit the land, soil type, or management system. Legumes including sainfoin, birdsfoot trefoil, purple prairie clover and white prairie clover contain condensed tannins which can reduce protein breakdown in the rumen and prevent bloat. Having protein digested in the small intestine instead of by the rumen bacteria contributes to more efficient animal growth. If these tannin-containing legumes are seeded in a mixture with alfalfa they will “actively” reduce bloat risk. Cicer milk vetch does not have tannins but is slower to digest so will not cause bloat.

As a non-bloating legume, animal gains on sainfoin pastures can be as efficient and rapid as on alfalfa pasture. Sainfoin is resistant to the alfalfa weevil, grows earlier in the spring and later in the fall. Researchers at AAFC Lethbridge have been selecting sainfoin for improved yield, regrowth and survival in alfalfa stands, and have found that sainfoin’s survival depends partly on the alfalfa variety it is grown with, as well as where it is grown.

More information about legume grazing strategies and research being conducted can be found in the following BCRC Factsheets:

Keeping legumes in pasture stands longer

Increasing fall productivity in winter-hardy alfalfa

Improving abiotic stress tolerance in alfalfa

Grazing Management Terminology

A working knowledge of grazing management terms and calculations is an extremely useful tool when planning and developing practical, successful grazing plans. The ability to prepare and estimate forage utilization means less uncertainty when dealing with management decisions in ‘real time’ once animals are grazing pastures.

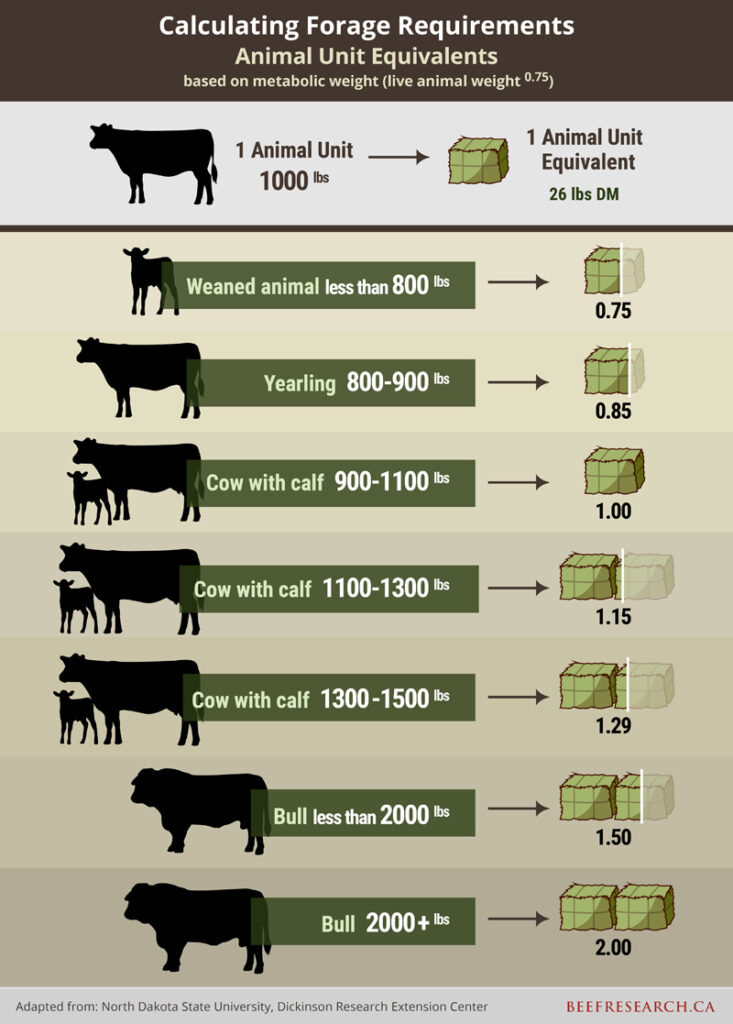

The animal unit (AU) is a standard unit used in calculating the relative grazing impact of different kinds and classes of livestock. One animal unit is defined as a 1000 lb (450 kg) beef cow with or without a nursing calf, with a daily dry matter forage requirement of 26 lb (11.8 kg).

An animal unit month (AUM) is the amount of forage to fulfill metabolic requirements by one animal unit for one month (30 days). One AUM is equal to 780 lbs (355 kg) of dry matter forage.

Forage requirements change with the size and type of animal. Metabolic weight (live weight to the 0.75 power) accounts for significant variation in dry matter intake among animals of different size and provides a more accurate estimate of forage demand. Animal Unit Equivalents (AUE) have been calculated for various species and sizes of animals. Table 1 provides beef cattle size categories and corresponding animal unit equivalents.

Table 1: Beef cattle size categories and corresponding animal units

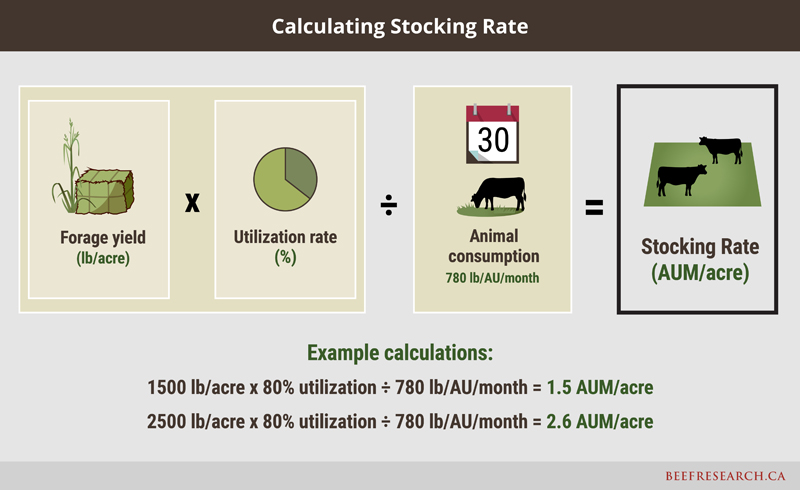

Stocking rate is the number of animals on a pasture for a specified time period and is usually expressed in Animal Unit Months (AUM) per unit area. For example, an area that supports 30 (1,000 lb) cows for a four-month grazing season has a stocking rate of 120 AUMs for that area. If the pasture is 100 acres in size, the stocking rate would be expressed as 1.2 AUM/acre (120 AUMs divided by 100 acres). Your stocking rate will not stay the same year after year, so you will need to adjust the number of animals you intend to graze to achieve the desired stocking rate for each pasture within your grazing system. Stocking rates must also take utilization rates for pastures into consideration. The utilization rate determines how much forage is used for grazing by cattle, but also how much is trampled or consumed by insects and wildlife.

Stocking rate (AUM/acre) = (Forage yield [lb/acre] x (Utilization rate [%] ÷ 100)) ÷ 780 lb/AU/month

Stock density is the number of animals in a particular area at any moment in time and is expressed as Animal Units (AU) per unit area. Stock density increases as the number of animals in a paddock increase or as paddock size decreases and is based on level of grazing management. For example, a herd of 30 (1,000 lb) cows on a 2 acre paddock fenced off within the larger 100 acre land base has a stock density of 15,000 lbs/acre (30 cows x 1,000 lbs/cow divided by 2 acres) or 15 Animal Units/acre (1 AU = 1,000 lb therefore 15,000 lbs/acre divided by 1,000 lb = 15 AU/acre), even though the stocking rate for the entire 100 acre pasture is 1.2 AUMs/acre. The difference between these two values is the time factor.

Carrying Capacity Calculations

Carrying capacity is the average number of animals that a pasture can support for a grazing season. Carrying capacity addresses the first principle of grazing management – balancing forage supply with livestock demand. The pasture’s ability to produce forage is measured in AUMs. The amount of forage consumed by a particular type of animal (i.e. cow-calf pair, yearling) is expressed in AUEs.

It is valuable to calculate carrying capacity prior to the grazing season as forage productivity shifts with time or condition (i.e. poor, fair, good, excellent) on existing pastures. As well, if producers recently acquire a pasture and have no historical stocking rate data available, calculating carrying capacity will help producers manage the pasture appropriately.

There are four important steps to estimating carrying capacity on a pasture:

- Map the range site (topography, soil types and zone) and vegetation types.

- Assess range health or tame pasture condition (e.g. poor, fair, good or excellent).

- Use provincial forage production guides – or use field-based sampling – to get an initial stocking rate (animal units) for the pasture.

- Monitor condition and adjust stocking rate as needed.

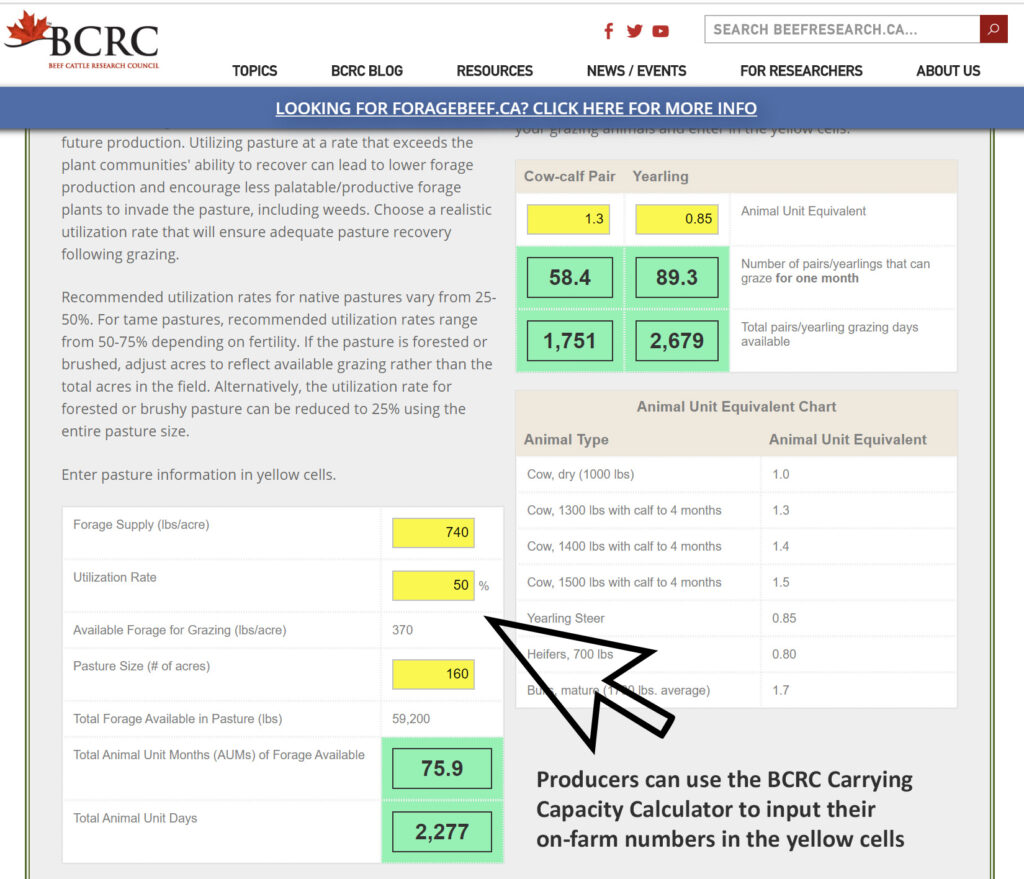

The BCRC Carrying Capacity Calculator is a decision support tool designed to help producers determine how much forage is available for grazing. Producers can use the Method 1 calculator if they wish to calculate an estimate of carrying capacity based on available provincial forage production guides. These estimates are based on projected forage productivity depending on soil type, annual precipitation, and pasture condition. Method 1 works best when the pasture condition (or range health) is similar throughout the field and the forage plant community (or range type) is uniform.

Producers can use Method 2 if they plan on clipping, drying, and weighing samples collected from their pasture. Field-based sampling provides greater accuracy but requires more hands-on work. Producers may choose field-based sampling if provincial guides are unavailable for their region or if pasture types or conditions vary within their field. Forage production varies each year, so the Method 2 approach should include multiple years of sampling to estimate the long-term productivity of the pasture.

In both methods of the calculator, producers can input their pasture acreage, their animal type (i.e. yearling, cow-calf pairs) as well as forage utilization rate in the yellow boxes. Recommended utilization rates for native pastures vary from 25-50%. For tame pastures, recommended utilization rates range from 50-75% depending on fertility levels.

- References

-

1 Voisin, A. 1988. Grass Productivity. Island Press. 358pp.

2 Gerrish, J.R., P.R. Peterson, and R.E. Morrow. 1995. Distance Cattle Travel to Water Affects Pasture Utilization Rate. American Forage and Grassland Council. Proc. 1995:61-65.

3 Gerrish, J.R. Beef Cattle Handbook – Grazing System Layout and Design. University of Wisconsin – Extension, Cooperative Extension.

4 Iwaasa, A. 2006. Carbon sequestration, methane production and nitrous oxide emissions from cattle grazing native prairie. http://www.beefresearch.ca/factsheet.cfm/pasture-management-and-productivity-56

5 Kopp, J. C., W. P. McCaughey, and K. M. Wittenberg. 2003. Yield, quality and cost effectiveness of using fertilizer and/or alfalfa to improve meadow bromegrass pastures. Canadian Journal of Animal Science 83.2: 291-298.

- Learn More:

-

Rangeland and Riparian Health

Beef Cattle Research Council

http://www.beefresearch.ca/research-topic.cfm/rangeland-and-riparian-health-82

Management of Intensive Grazing

Saskatchewan Agriculture

Video: What Really Matters in Grazing Management – Jim Gerrish

Western Beef Development Centre

Planning Pastures: Beef Research School episode

Beef Cattle Research Council

http://www.beefresearch.ca/blog/planning-pastures-video/

Grasslands Beneficial Management Practices

Grazing Alfalfa

Volesky, Jerry D., and Bruce Anderson. University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension (1999).

Feedback

Feedback and questions on the content of this page are welcome. Please e-mail us at info@beefresearch.ca

Expert Review

This content was last reviewed February 2019.

This content was last reviewed September 2023.